In California, workers’ wages have stagnated and families struggle to keep up with the rising costs of living, while corporate profits have skyrocketed. Yet many profitable corporations in California pay zero or very little in state taxes year after year.

Big corporations have also benefited greatly from the 2017 Trump tax cuts and are poised to receive more benefits from the federal tax and budget bill just enacted by the Trump administration and congressional Republicans. Large tax breaks for corporations widen economic and racial inequality because they largely benefit corporate shareholders, who are disproportionately wealthy and white.

California policymakers should ensure that profitable corporations pay their fair share in state corporate taxes — which represent a tiny share of their expenses — to support the public services that Californians need and help mitigate the harms of federal cuts to health care, food assistance, and other basic needs programs.

State leaders can prevent profitable corporations from completely wiping out their tax bills with amassed tax credits by instituting permanent annual caps on business credits and deductions. In practice, this would ensure that corporations contribute to the state services and infrastructure they rely on to operate their business, just like all Californians do.

As state leaders look to blunt the harm of the federal budget on Californians with low incomes and the state’s finances, it’s clear that California’s corporate tax structure is in need of repair. While large, profitable corporations benefit from new federal tax breaks, California policymakers must ensure these businesses pay their fair share in state taxes. There is no one-size-fits-all solution: different options can all complement each other. For example, limits on business tax credits and net operating loss (NOL) deductions are key to preventing the erosion of the potential revenues that could be generated from eliminating the water’s edge tax loophole and increasing the tax rate on highly profitable corporations.

MORE IN THIS SERIES

To learn more about the water’s edge election, net operating losses, tax credits, corporate tax rates, and options for common-sense reform, see the other fact sheets in this series:

- Water’s Edge: Closing the Largest Corporate Tax Loophole in California

- Profitable Corporations Can’t Keep Paying Zero in California State Taxes

- Legal Loopholes: How Corporations Reduce Their California Tax Bill

- A Graduated Corporate Tax Ensures California’s Most Profitable Corporations Pay Their Fair Share

Highly Profitable Corporations Can Largely Avoid State Taxes With Tax Credits and Net Operating Loss Deductions

A large share of corporations in California pay nothing above the meager $800 minimum franchise tax that most businesses that are incorporated, registered, or doing business in California are required to pay. Nearly half of all profitable corporations filing tax in California in 2023 — more than 300,000 corporations — paid nothing more than the $800 minimum tax, even though they collectively had $11.7 billion in state profits, according to preliminary data from the state’s Franchise Tax Board. This means they were able to eliminate their regular tax liability by either zeroing out their taxable income with net operating loss deductions, zeroing out their tax bill with tax credits, or some combination of the two. This number does not include corporations that were able to greatly reduce their tax bills but still paid some amount above the minimum tax. Unfortunately, there is no public data available indicating the number of corporations that pay minuscule shares of their profits in state taxes, or which corporations they are. However, public data show that many profitable corporations are able to avoid paying taxes at the federal level. While there are some differences in tax avoidance opportunities for corporations between federal and state law, some corporations paying low or no federal taxes may also be able to reduce or zero out their state taxes using similar state-level tax breaks.

How can corporations pay next to nothing in state taxes when they are profitable?

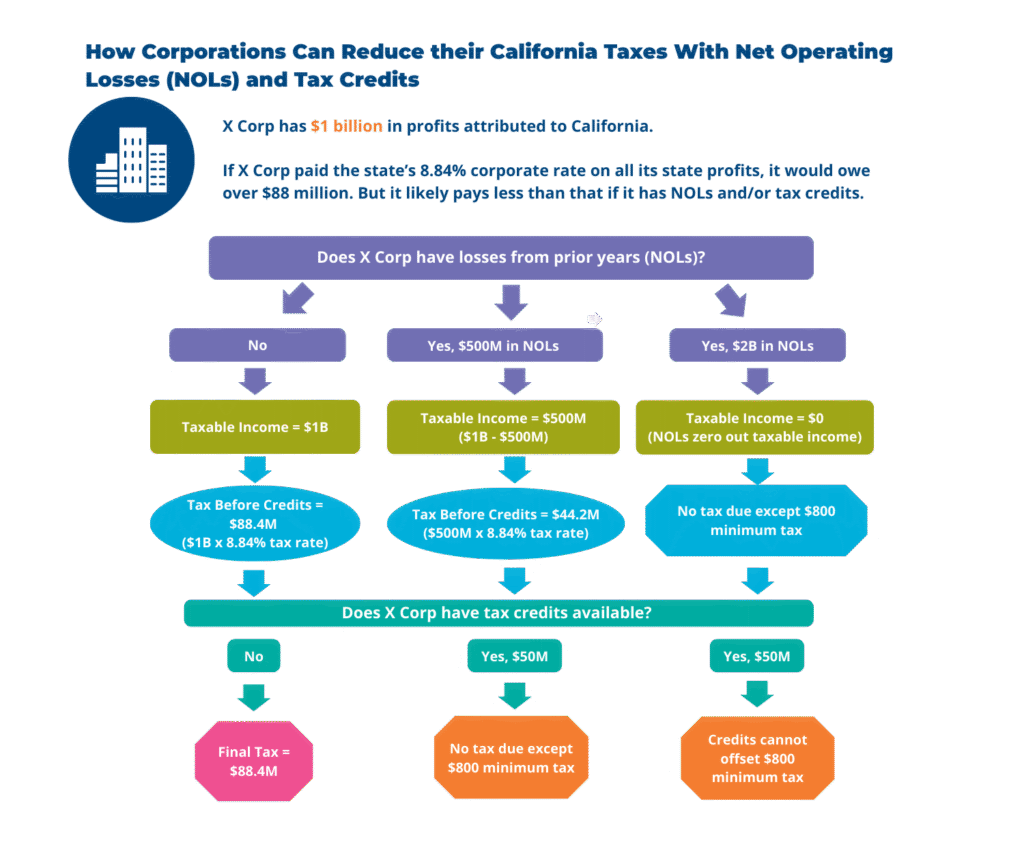

While business tax calculations can be very complicated, in general a corporation1This is a simplified example that does not include all the complexities of corporate tax calculations.:

- Determines its final tax bill by subtracting any tax credits it has available.

- Determines its total profits by subtracting business expenses from its total revenues/sales. For corporations that are part of a group of affiliated corporations, this calculation includes the profits of the entire combined group. However, multinational corporations can choose to use the “water’s edge election” and exclude the profits of their foreign subsidiaries, which can reduce their profits subject to state taxes and therefore their tax bill.

- Determines the share of these total profits that is attributable to California and to each member of the corporate group by multiplying profits by a “sales” factor — the ratio of the corporations’ California sales to total sales.

- Determines its taxable income for state tax purposes by deducting any net operating losses (NOLs) it has available.

- Determines its taxes due before applying tax credits by multiplying its taxable income by the applicable tax rate.2 While the state does have an “alternative minimum tax” for C corporations that utilize certain tax preferences, this does not prevent corporations from wiping out their taxes with credits, and impacts very few corporations. In 2022 and 2023,only around 1% of C corporation filers paid the alternative minimum tax, generating $100 million or less in state revenues (data is preliminary for 2023).

A net operating loss occurs when a business experienced losses in prior years, meaning its expenses exceeded its revenues. Those losses can be carried forward and used to reduce its taxable income in future years, and thus its tax bill.3NOLs can be carried forward for up to 20 years after the loss occurred, at which time any unused NOLs expire. In total, corporations reduced their taxable income by around $30 billion in 2023 and had more than $1.3 trillion in unused NOLs that can be carried forward and deducted from profits in future years, according to preliminary Franchise Tax Board data.

NOLs, if large enough, could reduce taxable income to zero, in which case the business would pay no more than the state’s $800 minimum franchise tax.

If a business still has taxable income after subtracting NOLs, the applicable tax rate — 8.84% for C corporations and 1.5% for S corporations — is then applied to determine its tax liability. But many businesses can then reduce their tax liability on a dollar-for-dollar basis if they have research and development (R&D) credits, film production credits, or other types of business credits. Some may even reduce their regular tax bill down to zero and would only pay the $800 minimum tax.

Like NOLs, business tax credits can also be carried forward to future years if their credits exceed the taxes they owe in the current year. According to data last reported by the Franchise Tax Board for the 2020 tax year, corporations had more than $40 billion in unused R&D credits that could be used to offset their future tax bills.4 This information is no longer reported by the Franchise Tax Board.

The R&D credit is by far the state’s largest business tax credit. The credit cost California more than $2.5 billion in 2023 and was claimed by over 4,600 corporations across various industrial sectors, according to preliminary Franchise Tax Board data. While research has generally found state R&D tax credits to increase the amount of R&D taking place in a state, the evidence is mixed on the size of the impact and their overall economic effects. Additionally, California’s credit has never been rigorously studied. The California State Auditor noted nearly ten years ago that, because there is no regular oversight or evaluation of the credit, the auditor’s office could not determine whether the credit was fulfilling its purpose or benefitting the state’s economy. Thus, it is unclear whether the billions of dollars the state spends on the credit each year are an effective use of public funds — especially given that those dollars are not available to spend on other public services that could potentially provide greater economic benefits.

While the Franchise Tax Board does not report tax credit data for individual corporations, some of these corporations do report in their public financial filings the amount of California credits — particularly R&D credits — they have available to offset future tax liability. For example, Alphabet (Google’s parent company) and Apple report that they have $6.4 billion and $3.5 billion, respectively, in California R&D credits that they can use to reduce their California taxes in the future. This means that even if companies like this with large stockpiles of credits were subject to a higher tax rate in the future, some of them could largely avoid paying more in tax as long as they still have sufficient credits available for use.

Profitable Corporations Shouldn’t Be Able to Wipe Their Entire Tax Burden: State Policymakers Should Place Annual Limits on Net Operating Loss Deductions and Tax Credits

California policymakers can make sure profitable corporations pay their fair share in state taxes by enacting permanent annual limits on NOL deductions and tax credits.

State leaders have temporarily limited NOLs and tax credits multiple times in response to budget shortfalls. In 2020, in response to the COVID-19 economic crisis, state leaders enacted a $5 million limit on tax credits that businesses could use in a given year and a pause on the use of NOL deductions for businesses with state profits above $1 million. Those limitations were in effect for tax years 2020 and 2021. However, even with those limitations in place, a large share of profitable corporations still paid nothing more than the $800 minimum tax in those years, as shown in the first chart above.

The Legislative Analyst’s Office estimated in 2022 that the $5 million tax credit limit likely impacted fewer than 100 corporations, since most businesses claim tax credits below that amount. The credit limit is estimated to increase state revenues by $2 billion or more annually in years when it’s in effect.

Faced with another shortfall in 2024, policymakers still re-enacted these limits for tax years 2024, 2025, and 2026.

BAD BUDGETING

Breaking from tradition — and likely to appease corporate opponents to these limits — policymakers also included a provision in the 2024-25 budget that will allow businesses impacted by the temporary tax credit limitation to claim refunds after 2026 for the credits that they were prohibited from taking during the limitation period. In other words, they can receive cash back if their delayed credits exceed the taxes they owe in those years. Historically, refundable tax credits have only been available for low-income families and individuals in California as a way to boost their incomes. Allowing corporations to claim refunds for these credits will cost the state more than $1 billion annually for several years beginning in 2027, as the corporations electing to receive refunds must spread the refund out over several years. Policymakers could avoid these costs in the out years by repealing this refundability provision.

Policymakers have several options to limit business tax credits to a reasonable amount on an ongoing basis. They could opt to make the current temporary $5 million limit permanent instead of letting it expire in 2027. They could also reduce that limit in the near term to generate additional revenues immediately. Another option is to limit the total credits that a business can use in any year to a percentage of the taxes it would otherwise owe that year. In the longer term, rigorous analyses on the efficacy and the cost-effectiveness of specific business tax credits — such as the R&D credit and the film tax credit — are warranted, which would inform future policy reforms such as eliminating or restructuring credits determined to be ineffective or where the costs exceed the benefits.

Similar to limiting tax credits, state leaders could limit the amount of NOL deductions that can be taken in a given year as a percentage of the business’ state profits. While there are legitimate reasons to allow businesses to use NOL deductions to “smooth out” their income over multiple years, since income may be volatile for some businesses, there is also an argument to be made that businesses should not be able to pay nothing or next to nothing in years when they are generating significant profits. So it is reasonable to impose annual limits to prevent corporations from entirely wiping out their taxable income and in turn, their tax bill. At the federal level, NOL deductions are limited to 80% of a corporation’s taxable income. California could adopt that limit or enact a tighter limit to raise additional revenue and ensure corporations are paying taxes on more than 20% of their profits.

Placing reasonable caps on business credits and deductions — particularly in combination with the other corporate tax reforms such as eliminating the water’s edge loophole and increasing the tax rate on the most profitable corporations — will ensure corporations contribute a fair share of their profits in California taxes to support the state services and infrastructure that allow companies, their workers, and their consumers to thrive.