New Census figures released today show promising gains in income and employment for Californians, yet also show that millions of California residents are still struggling to get by on extremely low incomes. These data underscore the need for policymakers to ensure that the economy’s recent gains are shared among all Californians.

The latest Census figures indicate that median household income in California grew to $71,805 in 2017, an increase of 3.8% over the prior year after adjusting for inflation. Median family income and median earnings for all workers also increased compared to inflation-adjusted income and earnings in 2016, and a larger share of Californians were employed. These positive economic gains are encouraging, but must be considered within the context of the slow speed overall with which the California economy has recovered from the Great Recession. Compared to 2007, when California incomes peaked before the Great Recession, median household income has only increased by 1.1% after adjusting for inflation. This modest real change in the incomes of typical households, this far into the economic recovery, helps explain why many Californians report that they do not feel economically secure, despite the state’s improving job market.

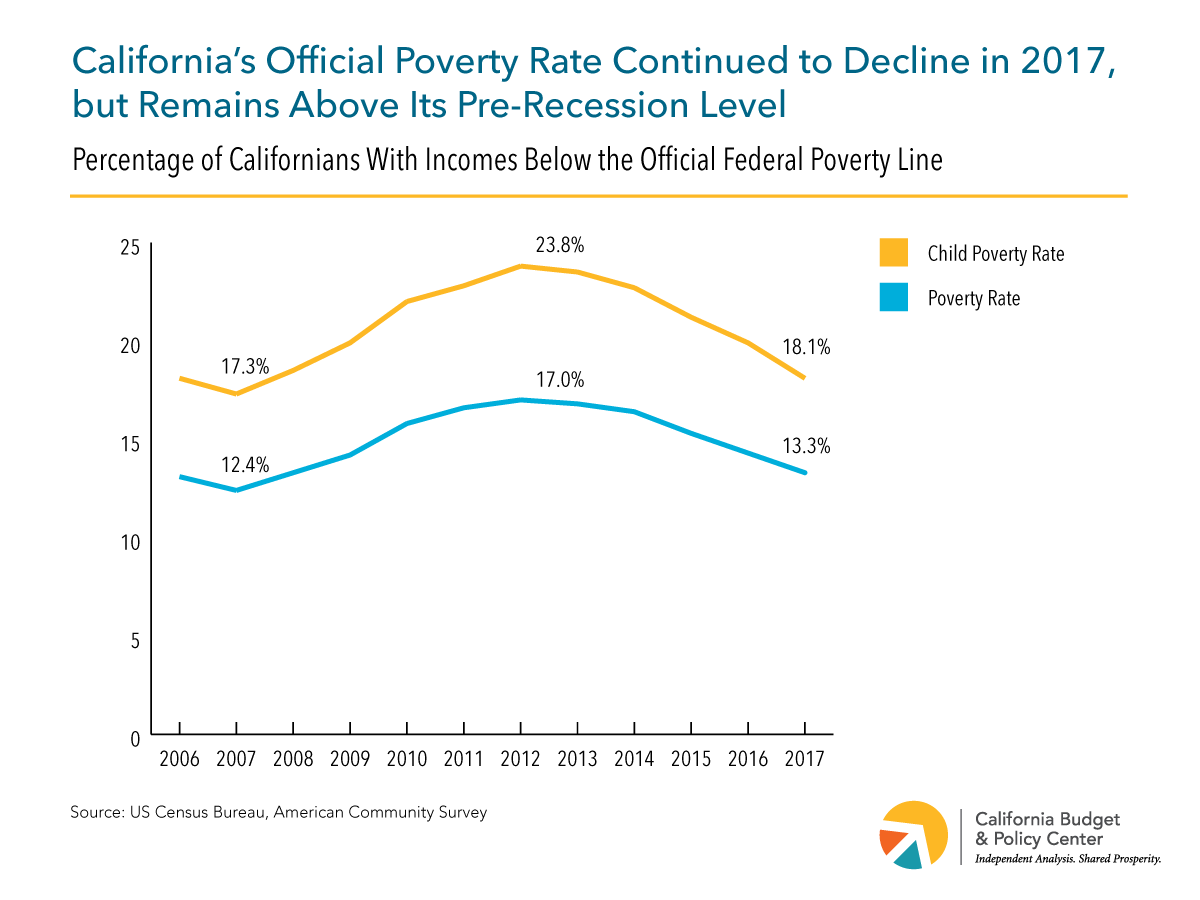

More troubling are new data from the Census that show that millions of people in California continue to struggle to get by on extremely low incomes. On the positive side, California’s official poverty rate of 13.3% for 2017 was lower compared to the previous year, when it was 14.3%. The state’s official child poverty rate also dropped to 18.1% in 2017, from a rate of 19.9% in 2016. However, 5.2 million Californians, including 1.6 million children, still lived in poverty in 2017 based on the official poverty measure. For a family of two adults and two children, for example, this means living on an annual cash income of less than about $24,900. Moreover, the state’s poverty rate and child poverty rate under the official poverty measure still have not dropped to their pre-Great Recession levels.

Also troubling, 2.2 million individuals, including 600,000 children, lived in deep poverty in 2017 based on the official poverty measure, meaning that their families had cash incomes of less than half of the official poverty threshold last year, or less than about $12,400 for a two-parent family with two children. The state’s deep poverty rates of 5.8% overall and 7.2% for children were lower than in 2016 (when they were 6.2% overall and 8.1% for children), but remain problematically high.

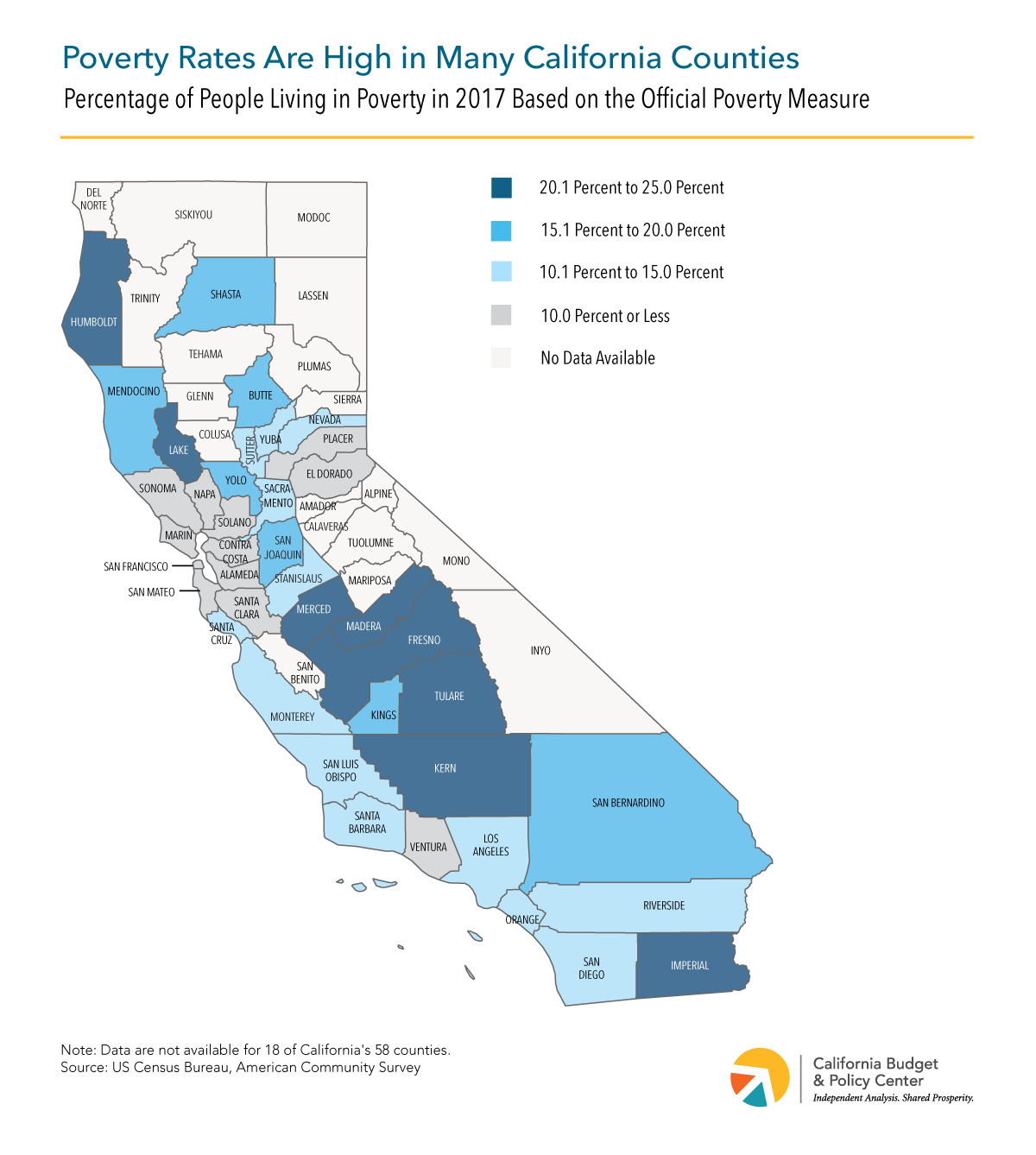

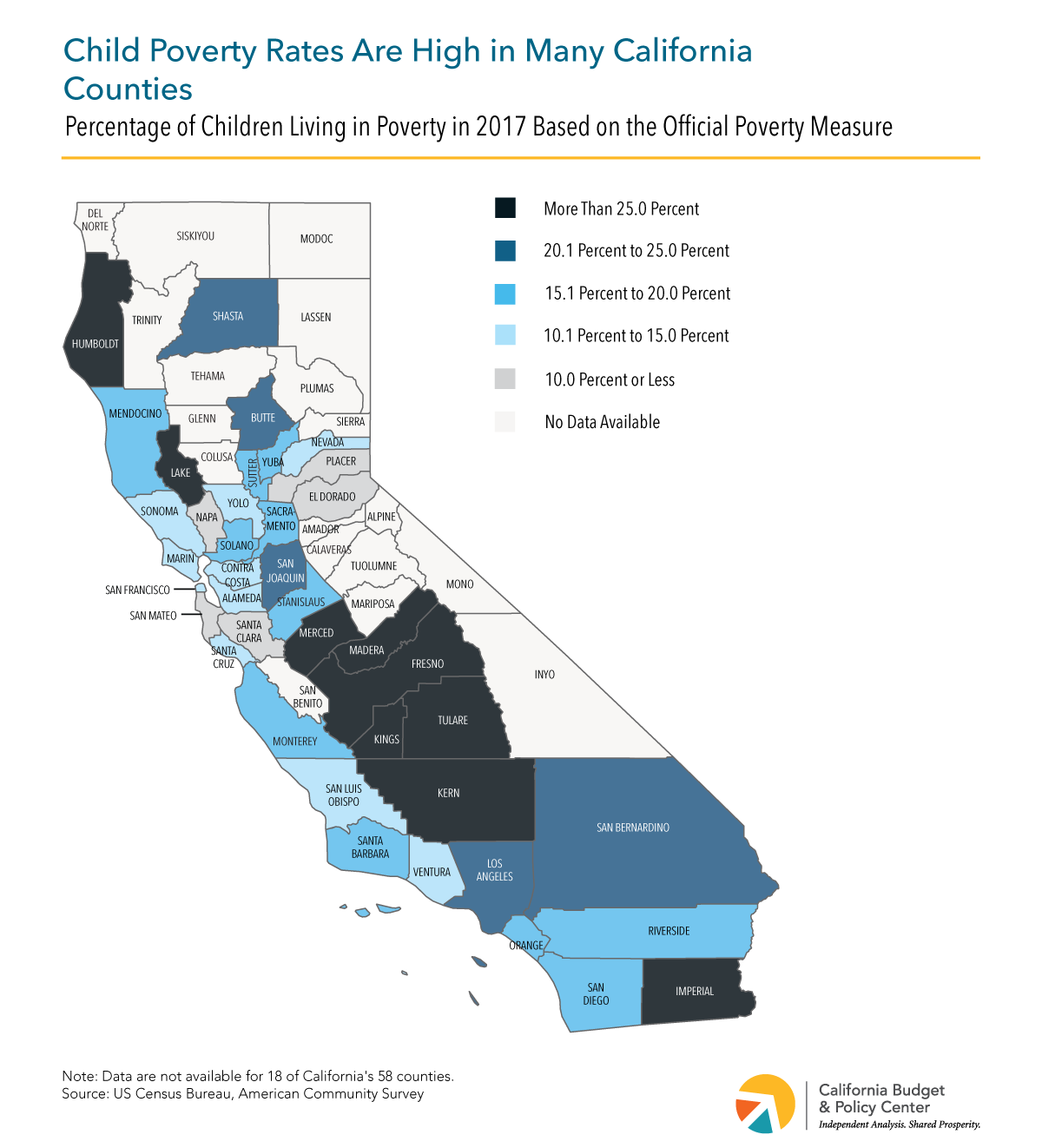

The latest Census figures also show that there are stark differences in people’s economic well-being across California’s counties. In 2017, the official poverty rate ranged from a low of 5.6% to a high of 24.6% across the counties, while the official child poverty rate ranged from 3.2% to 37.1%. In eight counties, more than 1 in 5 people lived in poverty, largely in the Central Valley (see Map 1). Additionally, more than 1 in 5 children lived in poverty in 14 counties, and this includes four counties — again, most in the Central Valley — where over 30% of children were in poverty (see Map 2).

Map 1

Map 2

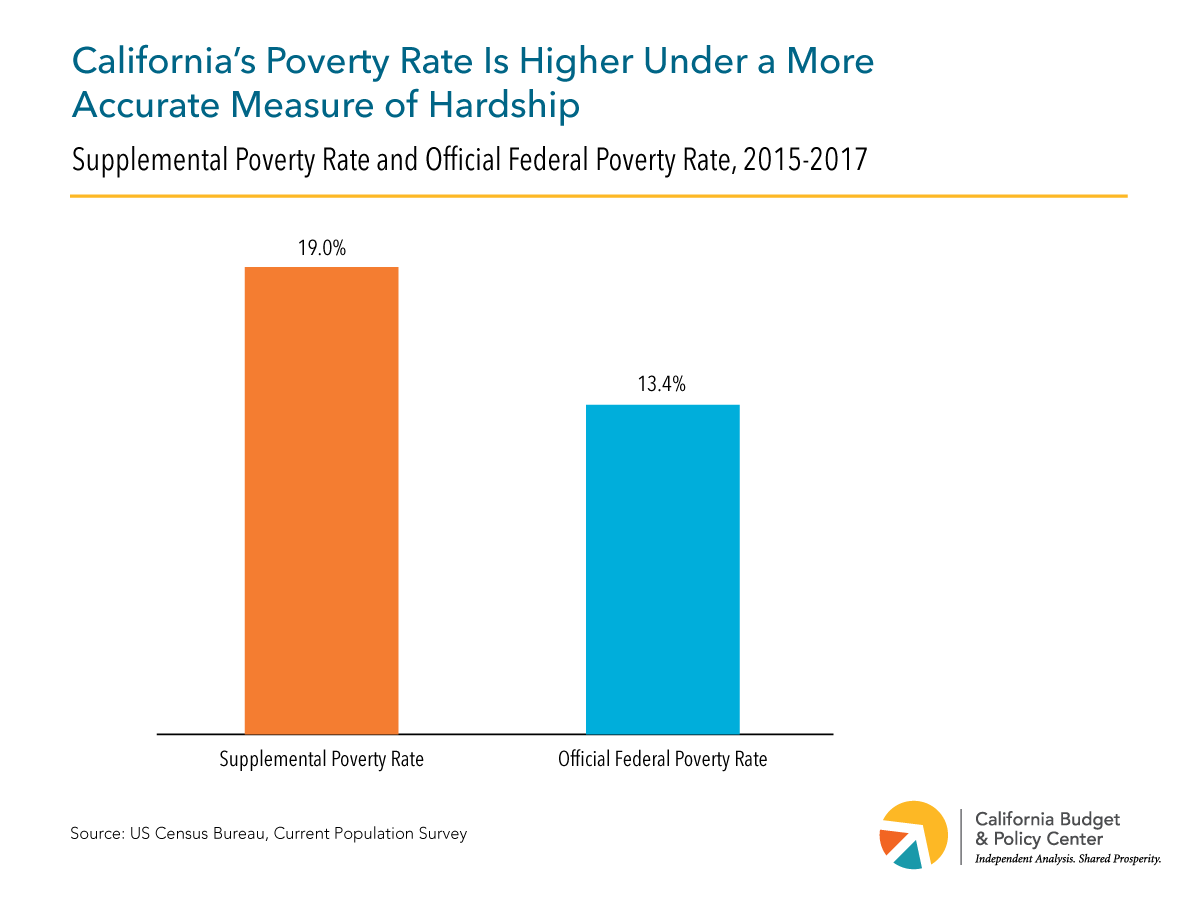

Although these Census figures published today show that poverty remains unacceptably high in California, they actually understate the problem of economic hardship in the state because they reflect an outdated measure of poverty. Census figures released yesterday based on an improved measure — the Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM), which accounts for the high cost of housing in many parts of the state — show that roughly 7.5 million Californians per year, nearly 1 in 5 state residents (19.0%), could not adequately support themselves and their families between 2015 and 2017. Under this more accurate measure of hardship, California continues to have one the highest poverty rates and by far the most residents in poverty of the 50 states.

The new Census poverty figures underscore the need for policymakers to do more to ensure that all people can share in our state’s economic progress. Some current state-level policy planning efforts, including the Lifting Children and Families Out of Poverty Task Force and the Assembly Blue Ribbon Commission on Early Childhood Education, represent important opportunities to prioritize investments that will help Californians avoid and overcome poverty and address the serious negative consequences of living in poverty.

Other specific steps that policymakers can take include:

- Reject steep cuts to public supports that help families make ends meet and get ahead. Public supports such as food assistance through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) (CalFresh in California) provide vital resources to help Californians make ends meet now, while also helping children in poverty succeed over the long-term, according to research. Yet this month federal policymakers are considering changes to SNAP that would reduce the number of individuals able to access this support. People in communities throughout the state would likely be harmed.

- Help families afford their basic needs. With housing costs far outpacing many families’ earnings in recent years, it has become increasingly challenging for people with low incomes to keep a roof over their heads. Over half of California renters are housing cost-burdened, meaning that they pay more than 30 percent of their income toward housing, and nearly a third spend more than half of their income on housing. Since housing costs are most families’ biggest basic expense, addressing the housing affordability crisis is key to broadening economic security in California. Voters will have the chance to consider multiple ballot measures this fall that aim to address the state’s housing challenges (which will be discussed in upcoming Budget Center blog posts and publications). Continuing to invest in affordable child care, another major basic expense for many working families, can also make a difference.

- Make sure workers earn enough to support themselves and their families. Most families in poverty work, which means that low pay and not enough work hours are key barriers to economic security and opportunity. California’s recent decision to gradually raise the state’s minimum wage to $15 per hour by 2023 has already made a difference for the lowest-paid workers in our state. California policymakers have also supported low-wage workers by creating the CalEITC — a refundable state tax credit that helps low-earning workers pay for basic necessities — and expanding it in recent years to benefit all full-time minimum wage working parents and self-employed workers as well as low-income working young adults and seniors. Policymakers could build on this important investment by increasing the size of the CalEITC, particularly for working adults without dependent children; extending the credit to workers who remain excluded (such as those filing taxes with an Individual Taxpayer Identification Number); expanding access to free tax preparation services; and ensuring that CalEITC funding is protected in future economic downturns, when tax revenues are lower but need is even greater.