Introduction

The California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) program provides modest cash assistance to about 755,000 low-income children and their parents. It also helps parents overcome barriers to work and find jobs through key support services such as subsidized child care and transportation reimbursement.[1] As this Brief outlines, although Governor Newsom proposed new funding for CalWORKs grants in his 2019-20 budget proposal, the declining value of the earned-income disregard (EID) would reduce the economic impact of these investments, especially in the face of a rising state minimum wage.

A Fixed Earned-Income Disregard Does Not Serve CalWORKs Families

As parents who are participating in CalWORKs enter the workforce, the earned-income disregard allows families to continue to receive benefits while earning a paycheck — up to a certain limit. Specifically, the EID is the amount of a recipient’s gross monthly earnings that is overlooked when their grant levels are calculated. Since CalWORKs’ implementation in 1997-98, state law has exempted the first $225 of monthly earnings, then 50% of the remainder.[2] As a family’s earnings increase, their grant amount decreases until they reach the CalWORKs income limit. The income limit, which is partly based on the maximum monthly grant and the earned-income disregard, determines when a family is no longer eligible for CalWORKs cash assistance. The greater the value of the disregard, the smaller the reduction in the monthly grant and the more parents can earn before losing eligibility. This allows for a smoother transition out of the CalWORKs program.

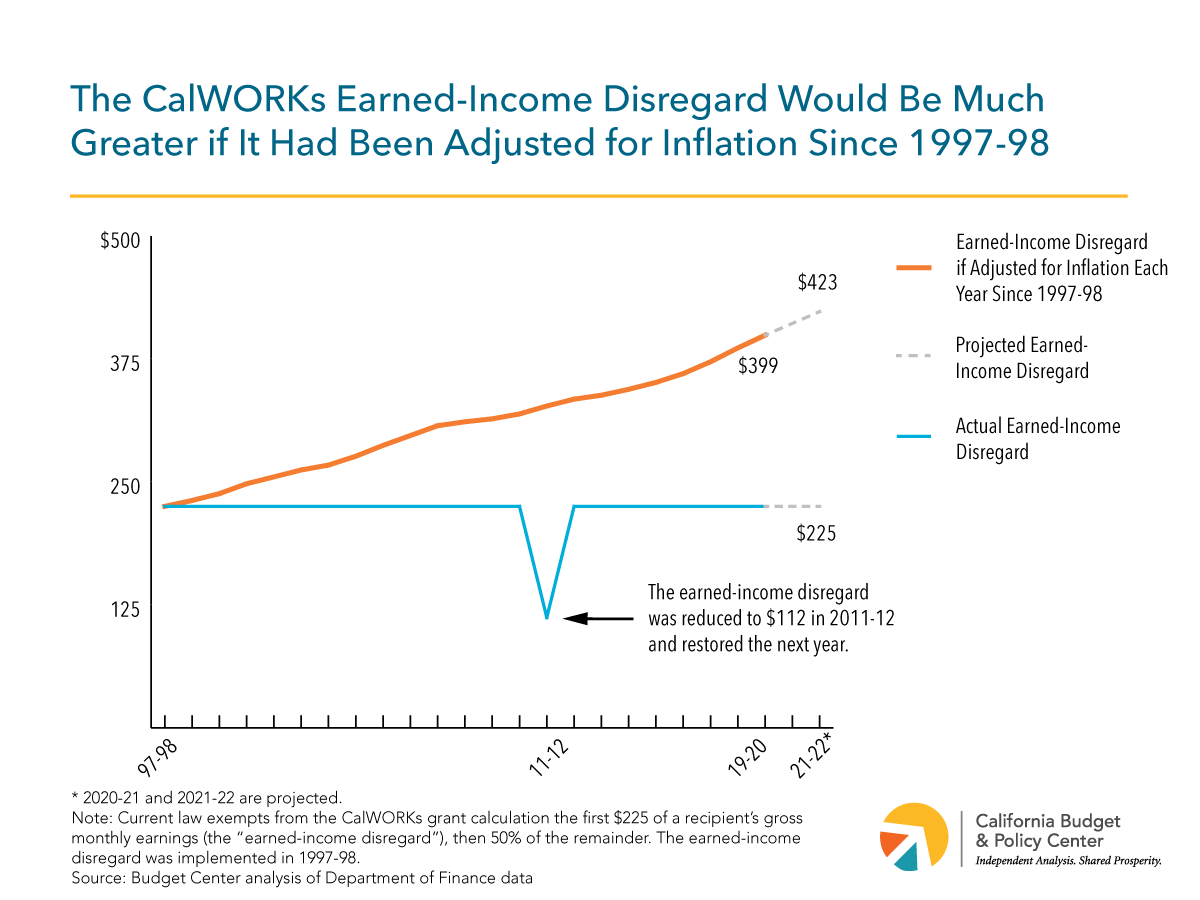

Unfortunately, the value of the EID has not changed in more than 20 years, leaving families with fewer resources (Figure 1). With the current $225 disregard, the annualized income limit in 2019-20 will be $23,772 (or $1,981 a month) for a family of three in a high-cost county. If policymakers had increased the disregard each year to account for inflation, the EID would have been $399 in 2019-20. Families would have had up to $25,858 in annual income (or $2,155 a month) before reaching the income limit. For working families who face rising rents and find it harder each year to keep a roof over their heads, that extra $174 a month is substantial.[3] In other words, policymakers’ failure to increase the disregard to keep up with the rising cost of goods and services has left already struggling families with even fewer resources to make ends meet in our state.

Figure 1

The Earned-Income Disregard Has Fallen Behind the State Minimum Wage

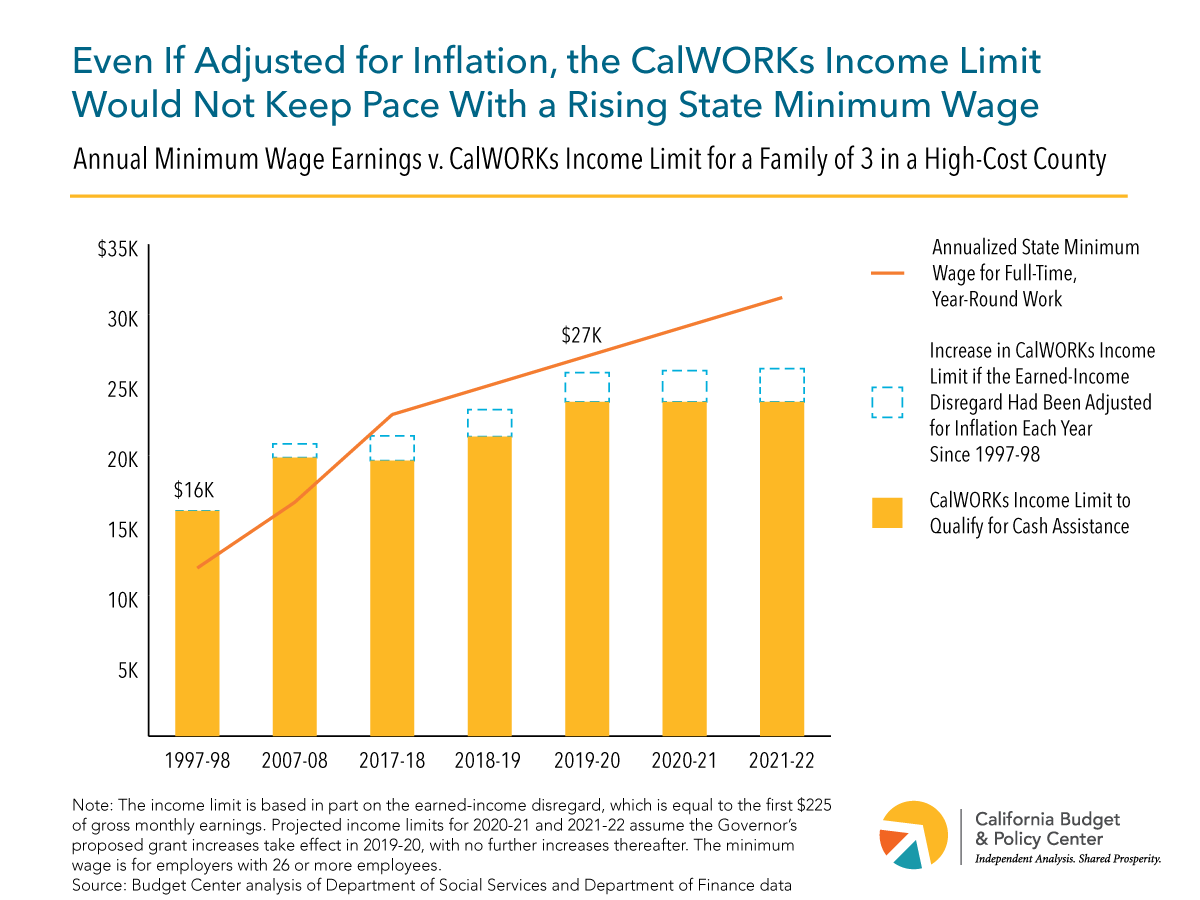

However, with a rising state minimum wage, policymakers would need to do more than adjust the EID for inflation if CalWORKs is to better support families pursuing employment (Figure 2). When CalWORKs was first implemented in 1997-98, a parent working a minimum wage job full-time and year-round earned $11,960 a year (or $5.75 an hour), well-below the annualized income limit of $16,020 (or $7.70 an hour). In 2019-20, that same parent would be ineligible for assistance because the annualized income limit of $23,772 (or $11.43 an hour) would be below minimum wage earnings of $27,040 (or $13.00 an hour). Even if the disregard had been adjusted for inflation, the annualized income limit would still fall short.[4] The gap between minimum wage earnings and the CalWORKs income limit is only projected to grow in the coming years. By 2021-22, when the minimum wage hits $15.00 an hour, working more than the required 30 hours a week at minimum wage could mean a single-parent family automatically loses support.[5]

Figure 2

State Policymakers Should Raise the CalWORKs Income Limit by Increasing the Earned-Income Disregard and Tying the Disregard to Inflation

During and after the Great Recession, state leaders made cuts to the CalWORKs program that undermined economic security for families with very low incomes. In recent years, policymakers have begun to reinvest in the program by boosting the value of CalWORKs grants. California’s leaders should continue to invest in CalWORKs by also increasing the earned-income disregard to better reflect changes made to the state minimum wage. An increase to the disregard would raise the income limit without penalizing parents for working more hours, especially for minimum-wage earners. Furthermore, to keep the disregard from losing value in the future, policymakers should ensure that the EID is increased annually to keep pace with inflation.

Esi Hutchful prepared this Issue Brief. The Budget Center was established in 1995 to provide Californians with a source of timely, objective, and accessible expertise on state fiscal and economic policy issues. The Budget Center engages in independent fiscal and policy analysis and public education with the goal of improving public policies affecting the economic and social well-being of low- and middle-income Californians. General operating support for the Budget Center is provided by foundation grants, subscriptions, and individual contributions. Support for this Issue Brief was provided by First 5 California.

[1]Legislative Analyst’s Office, The 2018-19 Budget: Analysis of the Health and Human Services Budget (February 16, 2018).

[2] For example, if a single mother with two children earns $500 a month, the first $225 she earned that month would not count towards the calculation of her grant, leaving $275. Then, half of that ($137.5) would be subtracted from the grant. The $225 disregard was reduced to $112 in 2011-12 but restored the year after. See Legislative Analyst’s Office, Review of CalWORKs Changes in the 2012-13 Budget (March 13, 2013), p. 7.

[3] Alissa Anderson and Esi Hutchful, CalWORKs Grants Continue to Fall Short as Rents Keep Rising (California Budget & Policy Center: March 2018).

[4] If the earned-income disregard had been adjusted for inflation each year since 1997-98, the annualized CalWORKs income limit would be $25,858 in 2019-20. The hourly wage equivalent would be $12.43 an hour.

[5] Unless otherwise exempt, single parents must spend on average 30 hours a week each month engaged in welfare-to-work activities if they have a child over age 6 or 20 hours per week each month if the child is under age 6. Welfare-to-work activities include unsubsidized and subsidized employment, job training, and other activities to help participants with employment. See California Department of Social Services, CalWORKs Annual Summary: February 2018 (February 2018), p. xv.