View the PDF version of this Fact Sheet.

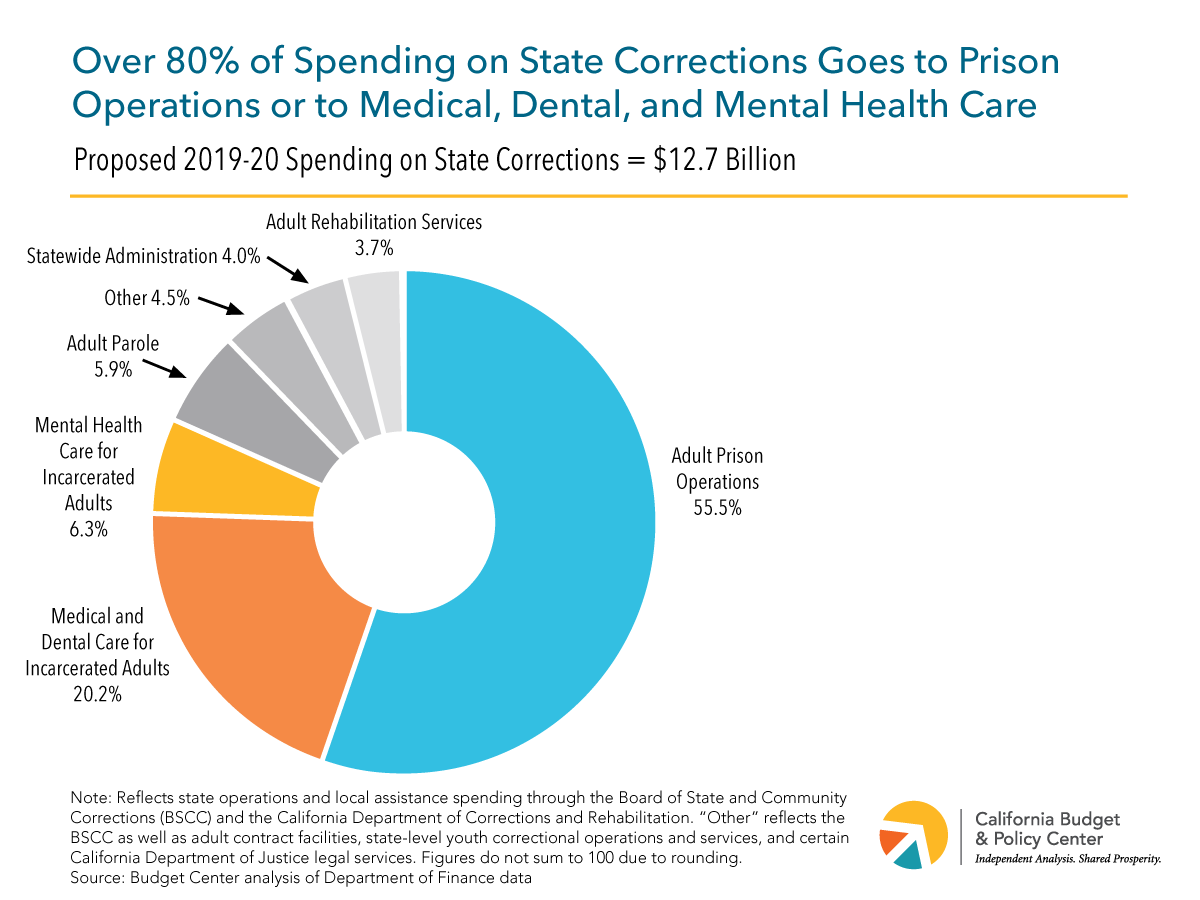

Governor Newsom’s proposed 2019-20 state budget includes $12.7 billion for state corrections.[1] The largest share of this proposed spending (55.5%, or $7.1 billion) goes to state prison operations. This includes the cost of salaries and benefits for correctional officers as well as the cost of various support services for incarcerated adults, such as meals and clothing.

The next-largest set of state corrections expenditures — totaling a proposed $3.4 billion in 2019-20 — pays for health-related services for incarcerated adults. Of this amount, $2.6 billion (20.2% of total spending on state corrections) is for medical and dental care and roughly $800 million (6.3% of the total) is for mental health care.

The fact that California spends hundreds of millions of dollars each year to provide mental health services in state prisons points to the prevalence of mental illness among incarcerated adults. Over 38,500 prisoners received mental health care in December 2017, the most recent month for which data are available.[2]

Moreover, the number of prisoners receiving mental health treatment has grown in recent years. In April 2013, these prisoners totaled 32,535 and accounted for less than 25% of all incarcerated adults.[3] By December 2017, this number had increased by more than 6,000 — to 38,561 — and was equal to nearly 30% of all incarcerated adults.[4] In contrast, during this same period the total number of adults incarcerated by the state declined by about 2,300, from 132,567 to 130,263.

Since the 1990s, a court-appointed officer has overseen mental health care delivery in California’s prisons to ensure that the state provides a constitutionally adequate level of care.[5] According to this officer, conditions are improving for prisoners who experience mental illness. “While more work remains to be done, [state officials] should take well-deserved encouragement from the progress they have made toward compliance.”[6]

Other observers note that prisons “are singularly ill-suited to house the mentally ill.”[7] People experiencing mental illness “are especially sensitive to the unique stresses and traumas of prison life, and their psychiatric conditions often deteriorate as a result.”[8] While California must continue to improve mental health care for incarcerated adults, reforms are also needed to address “the intersection between mental illness and criminal justice” so that Californians who need mental health treatment receive the appropriate care and do not end up in state prisons (or local jails).[9]

Support for this Fact Sheet was provided by the California Health Care Foundation.

[1] As used in this Fact Sheet, spending on “state corrections” reflects all funds budgeted through the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) and the Board of State and Community Corrections for state operations and local assistance. Several categories in the chart reflect the cost of both services and administration. In the case of dental and mental health care, the Department of Finance (DOF) combines the costs of administering these services into a single expenditure category. The Budget Center estimated the respective shares of administrative spending for dental care vs. mental health care in state prisons based on a methodology recommended by the DOF.

[2] California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, Offender Data Points: Offender Demographics for the 24-Month Period Ending December 2017 (no date), pp. 4 and 15.

[3] Matthew A. Lopes, Jr., Twenty-Sixth Round Monitoring Report of the Special Master on the Defendants’ Compliance With Provisionally Approved Plans, Policies, and Protocols (May 6, 2016), p. 3.

[4] The reasons for this increase are unclear. The CDCR suggests it may reflect the state’s improved ability “to assess, diagnose, and respond to [prisoners’] mental health treatment needs” as the prison population has declined and mental health-related staffing has increased. California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, An Update to the Future of California Corrections (January 2016), pp. 12-13.

[5] See Legislative Analyst’s Office, Overview of Inmate Mental Health Programs (March 16, 2017), p. 1, and California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, Notice: Decision in Mental Health Care Class Action (Coleman v. Brown) (no date).

[6] Matthew A. Lopes, Jr., Twenty-Sixth Round Monitoring Report of the Special Master on the Defendants’ Compliance With Provisionally Approved Plans, Policies, and Protocols (May 6, 2016), p. 123.

[7] Stanford Law School Three Strikes Project, When Did Prisons Become Acceptable Mental Healthcare Facilities? (February 2015), p. 7.

[8] Stanford Law School Three Strikes Project, When Did Prisons Become Acceptable Mental Healthcare Facilities? (February 2015), pp. 7-8.

[9] Stanford Justice Advocacy Project, The Prevalence and Severity of Mental Illness Among California Prisoners on the Rise (May 2017), p. 8.