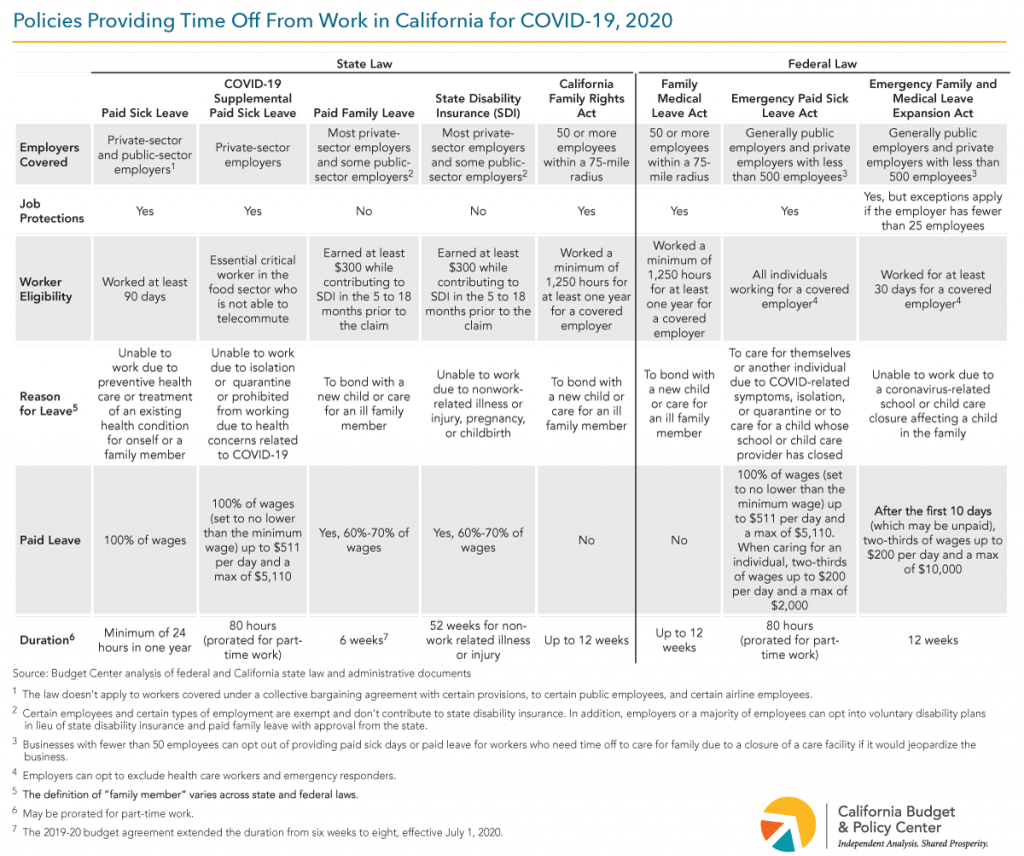

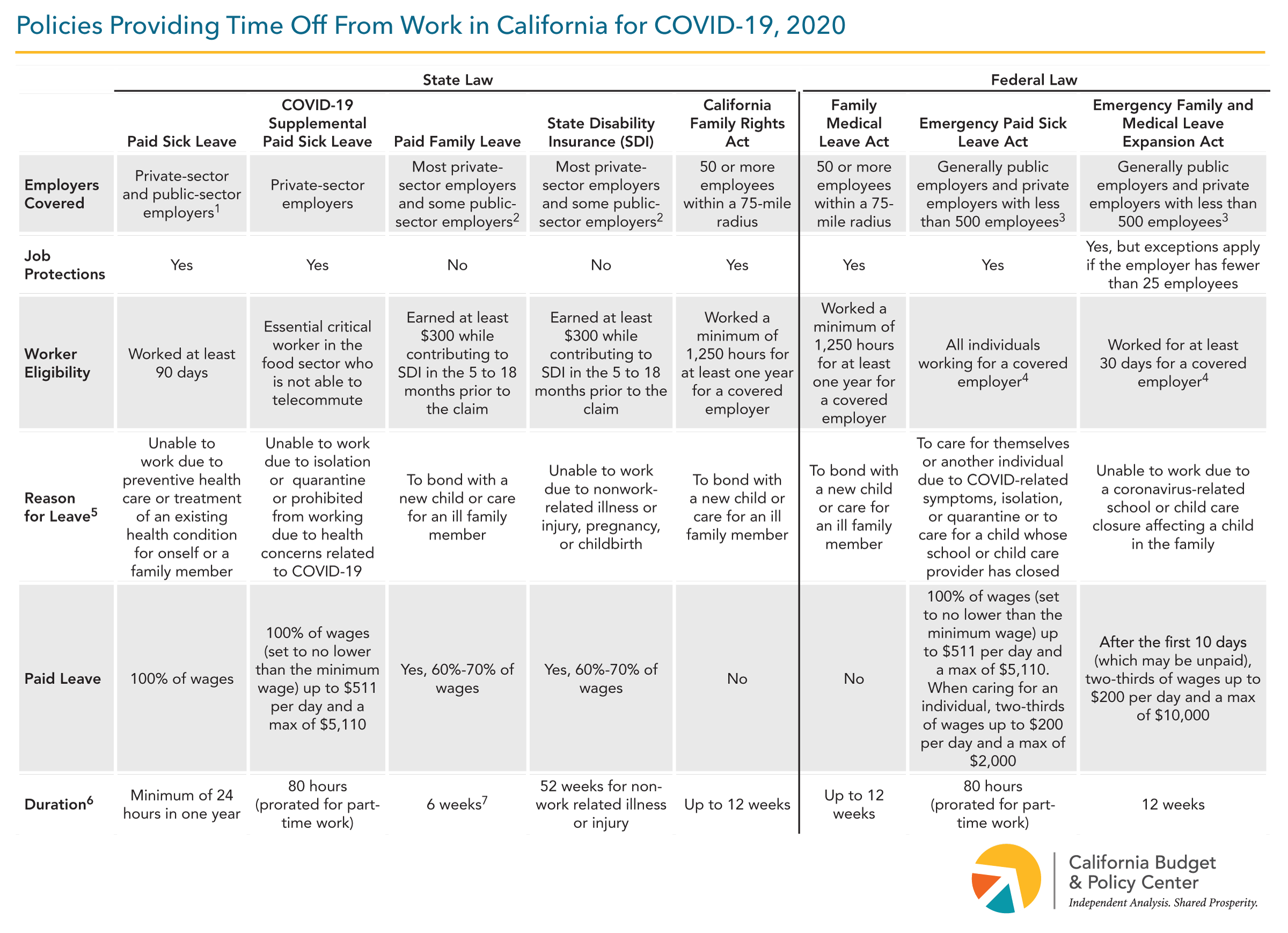

Choosing between paying the bills or caring for their families has never been an easy choice for California workers, and COVID-19 health and economic conditions have only exacerbated that dilemma. The federal Families First Coronavirus Response Act temporarily addresses workers’ lack of paid time off in the United States by requiring employers to provide both paid sick days and job-protected paid leave to care for a family member (see Table for more details). While the federal government will provide tax credits to businesses to cover the cost of the required leave policies, the federal law has exemptions that allow some employers to opt out of providing paid time off to workers, many of whom earn low wages, have limited benefits, and are at heighted risk of being exposed to COVID-19.

Workers ineligible for new federal leave laws may be able to rely on California’s family and medical leave laws, but these policies also have limitations that create barriers for workers taking paid time off from work. These barriers are particularly acute for workers with low wages – disproportionately women, Black, and Latinx workers. Finally, some workers may be covered by their employers’ benefits, but workers with low wages are far less likely to have paid time off via workplace benefits. This means that even as state leaders work to stop the spread of COVID-19 and have directed people to stay home, some workers cannot access paid time off to care for themselves or family members and still support their household needs.

How are workers caught in the paid time off gap?

Caught in the Gap: A part-time cashier at a nationwide pharmacy needs several weeks away from work to stay home to care for her spouse who is gravely ill and is under an isolation order, but she is ineligible for federal paid time off because she works for an employer with more than 500 employees. While this worker could use California’s paid family leave, she would not be able to take leave with job security because she works just 20 hours a week, which does not meet the requirements for job-protected leave under California law. Closing the Gap for Workers:

- Federal policymakers should require large businesses with more than 500 employees who are currently excluded in the Families First Act to provide paid time off. This could reach millions of additional workers in California.

- State policymakers should extend job protections to all workers who take family and medical leave regardless of the size of the employer, hours worked, or tenure.

Caught in the Gap: A single mom working at a small, local grocery story finds herself without care for her children due to the closure of local schools and day care centers. Her employer has told her that providing her with paid time off to care for her children would be a hardship that would jeopardize the business, and she is not eligible to utilize federal paid leave. California’s paid family leave program is not an option for parents who suddenly find themselves without care for their children due to a public health emergency. Her only option is to apply for unemployment insurance benefits. Closing the Gap for Workers:

- Federal leaders should limit small-business exemptions to those who would be forced to immediately close if they gave their employees paid time off under this new federal leave program. Currently, the Department of Labor definition of hardship is vague and requires only self-certification by small employers. Small businesses should also be required to submit a simple form to the federal Department of Labor, rather than current practice, which is to self-certify without any documentation.

- State policymakers should include care for a family member due to the closure of school, child care center, or adult day center during a public health emergency or natural disaster as a reason one can utilize paid family leave.

Caught in the Gap: A worker in the cleaning and maintenance department of a small, rural hospital fears he might have been exposed to COVID-19 when he dropped off groceries for his mother who has since tested positive for the virus. He knows he should self-quarantine for the recommended 14 days, but he only has three days of sick time under California’s paid sick days law and he’s worried about paying his bills. His employer has already informed him that he is considered a health care worker, and they won’t be providing any paid sick days under new federal laws. He could apply for state disability insurance, but he needs medical certification. Unfortunately, even though he works in a hospital, he does not have a primary care doctor, has been unable to schedule an appointment with a new doctor, and is afraid to go to urgent care due to the risk of spreading the virus or increasing his risk of exposure. Closing the Gap for Workers:

- Federal policymakers should provide health care workers and emergency responders with paid time off to care for themselves or their family. The regulations are overly broad and allow employers to exclude many workers, many of whom have a greater chance of being exposed to COVID-19, and they may need time off, too. Adding to their dilemma and economic hardship, many of these workers likely earn low wages, such as janitors in hospitals and factory workers building medical supplies.

- State policymakers should increase the minimum required number of paid sick days provided by all employers, which is currently just three days or 24 hours, to the equivalent of two weeks during a public health emergency and seven days when not in a public health emergency. Governor Newsom recently signed an Executive Order expanding paid sick days, but just for essential workers in the food sector who work for large employers currently excluded from federal law.

- State policymakers should waive medical certification necessary for state disability insurance or paid family leave during a public health emergency to ease the strain on the health care system.

Everyone needs time off to care for themselves or their families, and the COVID-19 pandemic has only heightened the necessity for all workers – crisis or not – to know they can safely keep their jobs and care for the health and well-being of loved ones. State and federal laws create a patchwork of policies to address the need for paid time off but leave notable gaps and workers without a reliable way to care for themselves and others. Both state and federal policymakers should take additional action in the midst of this public health and economic crisis to support California’s workforce in the same way workers show up for the economy every day.

Support for this work is provided by First 5 California.