The rise of a strong American middle class did not happen accidentally. It required a healthy economy supported by large and intentional public investments. These actions were largely structured to benefit whites to the exclusion of communities of color, and that decision bears serious moral and economic consequences for our future well-being. Nationally, whites are projected to become a racial minority by 2045.[77] In California, people of color already constitute the majority of the state’s population, and their share is projected to rise to more than two-thirds (68%) by 2045.[78] As a result, the economic welfare of people of color will increasingly determine the welfare of our state and of the larger society. Californians and all Americans need to decide which future we want. One option is to continue down our current path, disproportionately concentrating wealth and opportunity with a handful of whites, while locking out people of color. A better option is to improve public policies at the state and federal levels in order to ensure equitable investments in all of our people and create a strong and inclusive economy.

Appendix

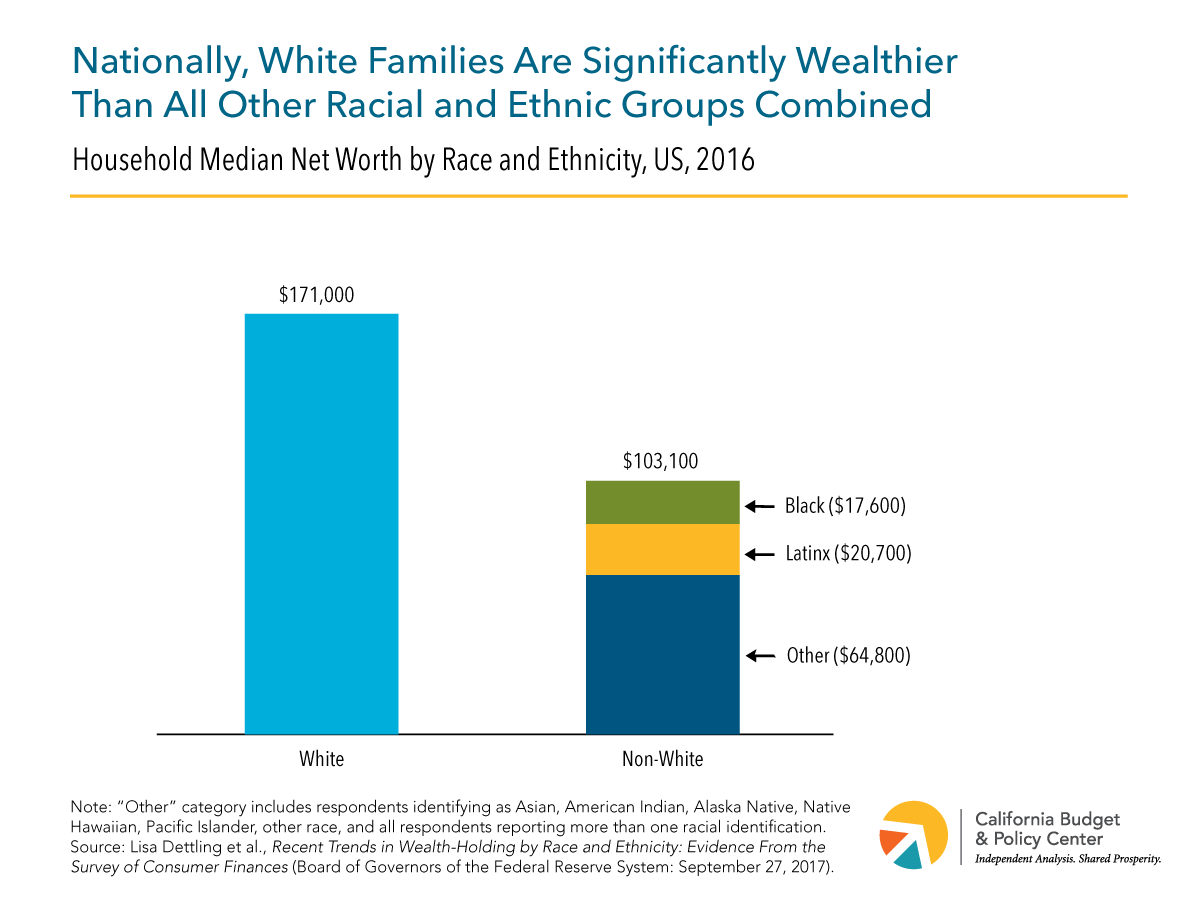

Measuring Wealth

Researchers primarily use three surveys to explore the distribution of wealth in the US: the US Census Bureau’s Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP), the Federal Reserve Board’s Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF), and the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) conducted by University of Michigan faculty. While all three of these surveys allow for comparisons by race and ethnicity, these categories tend to be limited. For example, due to sample size constraints, Asians, Native Americans, Pacific Islanders, and those who report more than one race are grouped into a single “Other” category, as in the SCF.[79] Wealth-related data by race and ethnicity is available for certain localities — including the Los Angeles area — from The National Asset Scorecard and Communities of Color survey (NASCC).[80] Due to these data limitations, The Racial Wealth Gap: What We Can Do About a Long-Standing Obstacle to Shared Prosperity focuses on the national differences in wealth between white, black, and Latinx households and reports local data when available.

Back to Top

Endnotes

[1] In this report, the term “racial wealth gap” is used to refer to an economic problem that affects various races and ethnicities.

[2] Jesse Bricker, et al., Changes in US Family Finances From 2013 to 2016: Evidence From the Survey of Consumer Finances (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System: September 2017), p. 10.

[3] Though these gaps decrease when accounting for other demographic and economic factors associated with wealth, sizable disparities remain. See Lisa Dettling, et al., Recent Trends in Wealth-Holding by Race and Ethnicity: Evidence From the Survey of Consumer Finances (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System: September 27, 2017).

[4] William Darity Jr., et al., What We Get Wrong About Closing the Racial Wealth Gap (Samuel DuBois Cook Center on Social Equity and Insight Center for Community Economic Development: April 2018), p. 9.

[5] Data are from the 2014 National Asset Scorecard and Communities of Color survey and are for Los Angeles and Orange counties. The authors do not account for nativity status, with the exception of distinguishing between US-born blacks and African blacks. Median net worth for African blacks was $72,000. See Melany De La Cruz-Viesca, et al., The Color of Wealth in Los Angeles (Duke University, The New School, the University of California, Los Angeles, and the Insight Center for Community Economic Development: March 2016), p. 40.

[6] Christian E. Weller and Jeffrey Thompson, Wealth Inequality Among Asian Americans Greater Than Among Whites (Center for American Progress: December 20, 2016).

[7] This analysis excludes retirement savings. Including retirement savings, black and Latinx Americans had $200 and $340 in median liquid wealth, respectively, while whites had $23,000. See Rebecca Tippett, et al., Beyond Broke: Why Closing the Racial Wealth Gap Is a Priority for National Economic Security (Center for Global Policy Solutions and Duke Research Network on Racial and Ethnic Inequality at the Social Science Research Institute: May 2014), p. 2.

[8] Data are from the 2014 National Asset Scorecard and Communities of Color survey and are for Los Angeles and Orange counties. The authors do not account for nativity status, with the exception of distinguishing between US-born blacks and African blacks. See Melany De La Cruz-Viesca, et al., The Color of Wealth in Los Angeles (Duke University, The New School, the University of California, Los Angeles, and the Insight Center for Community Economic Development: March 2016), p. 38.

[9] Lisa Dettling, et al., Recent Trends in Wealth-Holding by Race and Ethnicity: Evidence From the Survey of Consumer Finances (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System: September 27, 2017).

[10] Lisa Dettling, et al., Recent Trends in Wealth-Holding by Race and Ethnicity: Evidence From the Survey of Consumer Finances (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System: September 27, 2017).

[11] Thomas M. Shapiro, The Hidden Cost of Being African American: How Wealth Perpetuates Inequality (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), p. 190.

[12] Office of the Historian, United States Department of State, Indian Treaties and the Removal Act of 1830; Gregory P. Downs and Kate Masur, The Era of Reconstruction: 1861-1900 (National Park Service, US Department of the Interior: 2017), p. 70; and Masao Suzuki, “Important or Impotent? Taking Another Look at the 1920 California Alien Land Law,” The Journal of Economic History 64 (2004), pp. 125-130.

[13] Richard Rothstein, The Racial Achievement Gap, Segregated Schools, and Segregated Neighborhoods: A Constitutional Insult (Economic Policy Institute: November 12, 2014).

[14] Dedrick Asante-Muhammad, et al., The Road to Zero Wealth: How the Racial Wealth Divide Is Hollowing Out America’s Middle Class (Institute for Policy Studies and Prosperity Now: September 2017), p. 15.

[15] Jeremiah Battle, Jr., et al., Toxic Transactions: How Land Installment Contracts Once Again Threaten Communities of Color (National Consumer Law Center: July 2016), pp. 3-4.

[16] Under the 1968 Fair Housing Act, the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) had to investigate complaints of discrimination within 30 days. If HUD pursued the claim, it could only seek voluntary settlements with noncompliant parties or advise complainants to file private lawsuits, for which penalties were capped at $1,000. In 1988, Congress updated the Act to provide administrative enforcement of the law, extend HUD’s investigation time to 100 days, and increase the maximum civil penalties, which currently range from $20,111 for a first offense to $100,554 for those with a history of offenses. See Douglas S. Massey, “The Legacy of the 1968 Fair Housing Act” Sociological Forum 30 (2015), pp. 571-588; Administrative Conference of the United States, Enforcement Procedures Under the Fair Housing Act (June 18, 1992); and 82 Federal Register 24523 (2017).

[17] Douglas S. Massey, “The Legacy of the 1968 Fair Housing Act” Sociological Forum 30 (2015), pp. 571-588; Nikole Hannah-Jones, “Living Apart: How the Government Betrayed a Landmark Civil Rights Law,” ProPublica (June 25, 2015).

[18] US Department of Housing and Urban Development, Housing Discrimination Against Racial and Ethnic Minorities 2012: Executive Summary, (June 2013), p. 1.

[19] This analysis excludes durable goods. Dedrick Asante-Muhammad, et al., The Road to Zero Wealth: How the Racial Wealth Divide Is Hollowing Out America’s Middle Class (Institute for Policy Studies and Prosperity Now: September 2017), p. 8.

[20] Lisa Dettling, et al., Recent Trends in Wealth-Holding by Race and Ethnicity: Evidence From the Survey of Consumer Finances (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System: September 27, 2017).

[21] Lisa Dettling, et al., Recent Trends in Wealth-Holding by Race and Ethnicity: Evidence From the Survey of Consumer Finances (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System: September 27, 2017).

[22] Rebecca Tippett, et al., Beyond Broke: Why Closing the Racial Wealth Gap Is a Priority for National Economic Security (Center for Global Policy Solutions and Duke Research Network on Racial and Ethnic Inequality at the Social Science Research Institute: May 2014), p. 4.

[23] Lisa Dettling, et al., Recent Trends in Wealth-Holding by Race and Ethnicity: Evidence From the Survey of Consumer Finances (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System: September 27, 2017).

[24] Refundable tax credits are the exception, as they are recorded in the federal budget. See Lewis Brown Jr. and Heather McCulloch, Building an Equitable Tax Code: A Primer for Advocates (PolicyLink: 2014), p. 3.

[25] Lewis Brown Jr. and Heather McCulloch, Building an Equitable Tax Code: A Primer for Advocates (PolicyLink: 2014), p. 7.

[26] Heather McCulloch, Closing the Women’s Wealth Gap: What It Is, Why It Matters, and What Can Be Done About It (Closing the Women’s Wealth Gap Initiative: updated January 2017), p. 9; Suparna Bhaskaran, Pinklining: How Wall Street’s Predatory Products Pillage Women’s Wealth, Opportunities, and Futures (June 2016), p. 16.

[27] Scott Graves and Alissa Anderson, Payday Loans: Taking the Pay Out of Payday (California Budget & Policy Center: September 2008), p. 7.

[28] Suparna Bhaskaran, Pinklining: How Wall Street’s Predatory Products Pillage Women’s Wealth, Opportunities, and Futures (June 2016), p. 18-19.

[29] Suparna Bhaskaran, Pinklining: How Wall Street’s Predatory Products Pillage Women’s Wealth, Opportunities, and Futures (June 2016), p. 17.

[30] California Department of Business Oversight, Summary Report: California Deferred Deposit Transaction Law—Annual Report and Industry Survey (May 31, 2017), p. 8.

[31] In a 2013 analysis, these areas explained 61% of the ongoing racial wealth divide between whites and blacks. See Thomas Shapiro, Tatjana Meschede, and Sam Osoro, The Roots of the Widening Racial Wealth Gap: Explaining the Black-White Economic Divide (Institute on Assets and Social Policy: February 2013), pp. 2-3.

[32] Sara Kimberlin, Californians in All Parts of the State Pay More Than They Can Afford for Housing (California Budget & Policy Center: September 2017).

[33] Sara Kimberlin, Californians in All Parts of the State Pay More Than They Can Afford for Housing (California Budget & Policy Center: September 2017).

[34] Lisa Dettling, et al., Recent Trends in Wealth-Holding by Race and Ethnicity: Evidence From the Survey of Consumer Finances (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System: September 27, 2017).

[35] Lisa Dettling, et al., Recent Trends in Wealth-Holding by Race and Ethnicity: Evidence From the Survey of Consumer Finances (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System: September 27, 2017).

[36] California Budget & Policy Center analysis of US Census Bureau, American Community Survey data. Data are for household heads age 18 and older in 2016.

[37] Melany De La Cruz-Viesca, et al., The Color of Wealth in Los Angeles (Duke University, The New School, the University of California, Los Angeles, and the Insight Center for Community Economic Development: March 2016), p. 33.

[38] Thomas Shapiro, Tatjana Meschede, and Sam Osoro, The Roots of the Widening Racial Wealth Gap: Explaining the Black-White Economic Divide (Institute on Assets and Social Policy: February 2013), p. 2.

[39] Lisa Dettling, et al., Recent Trends in Wealth-Holding by Race and Ethnicity: Evidence From the Survey of Consumer Finances (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System: September 27, 2017).

[40] Thomas Shapiro, Tatjana Meschede, and Sam Osoro, The Roots of the Widening Racial Wealth Gap: Explaining the Black-White Economic Divide (Institute on Assets and Social Policy: February 2013), p. 3.

[41] Thomas Shapiro, Tatjana Meschede, and Sam Osoro, The Roots of the Widening Racial Wealth Gap: Explaining the Black-White Economic Divide (Institute on Assets and Social Policy: February 2013), p. 3.

[42] Laura Sullivan, et al., The Racial Wealth Gap: Why Policy Matters (Institute for Assets and Social Policy and Demos: 2015), p. 1.

[43] If black families owned their homes at the same rate as whites, the median black household’s wealth would increase by over $32,000 (451%). For Latinx families, equalizing homeownership rates would increase the median household wealth by over $29,000 (350%). Laura Sullivan, et al., The Racial Wealth Gap: Why Policy Matters (Institute for Assets and Social Policy and Demos: 2015), pp. 11-13.

[44] Thomas Shapiro, Tatjana Meschede, and Sam Osoro, The Roots of the Widening Racial Wealth Gap: Explaining the Black-White Economic Divide (Institute on Assets and Social Policy: February 2013), pp. 2-3.

[45] William Darity Jr., et al., What We Get Wrong About Closing the Racial Wealth Gap (Samuel DuBois Cook Center on Social Equity and Insight Center for Community Economic Development: April 2018), p. 7.

[46] William Darity Jr., et al., What We Get Wrong About Closing the Racial Wealth Gap (Samuel DuBois Cook Center on Social Equity and Insight Center for Community Economic Development: April 2018), p. 8.

[47] Laura Sullivan, et al., The Racial Wealth Gap: Why Policy Matters (Institute for Assets and Social Policy and Demos: 2015), p. 25.

[48] Heather McCulloch, Closing the Women’s Wealth Gap: What It Is, Why It Matters, and What Can Be Done About It (Closing the Women’s Wealth Gap Initiative: updated January 2017), p. 7.

[49] The data refers specifically to defined contribution plans. See Heather McCulloch, Closing the Women’s Wealth Gap: What It Is, Why It Matters, and What Can Be Done About It (Closing the Women’s Wealth Gap Initiative: updated January 2017), p. 12.

[50] Tatjana Meschede, et al., “‘Family Achievements’? How a College Degree Accumulates Wealth for Whites and Not for Blacks,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 99 (2017), p. 123.

[51] Hans Johnson, Testimony: The Need for College Graduates in California’s Future Economy (The Public Policy Institute of California: November 1, 2017).

[52] Jon Stiles, Michael Hout, and Henry Brady, California’s Economic Payoff: Investing in College Access and Completion (The Campaign for College Opportunity: April 2012), p.13.

[53] Amy Rose, State Spending Per Student at CSU and UC Remains Well Below Pre-Recession Levels, Despite Recent Increases (California Budget & Policy Center: March 2018).

[54] Yunju Nam, et al., Bootstraps Are for Black Kids: Race, Wealth, and the Impact of Intergenerational Transfers on Adult Outcomes (Insight Center for Community Economic Development: September 2015), p. 8.

[55] Tatjana Meschede, et al., “’Family Achievements?’ How a College Degree Accumulates Wealth for Whites and Not for Blacks,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 99 (2017), p. 124.

[56] There are three types of Cal Grant awards: Cal Grant A is used for tuition and fees; Cal Grant B provides an allowance for living costs known as an “access award” (in addition to tuition and fee assistance after the first year); and Cal Grant C is for students who attend occupational or career colleges. See California Student Aid Commission, What Is a Cal Grant Award?

[57] Data are from 2008. See The Campaign for College Opportunity, The State of Higher Education in California: Latinos (April 2015), p. 18 and The Campaign for College Opportunity, The State of Higher Education in California: Blacks (May 2015), p. 29.

[58] The Campaign for College Opportunity, The State of Higher Education in California: Latinos (April 2015), p.19; The Campaign for College Opportunity, The State of Higher Education in California: Blacks (May 2015), p. 29; and Amy Rose, Barriers to Higher Education Attainment: Students’ Unmet Basic Needs (California Budget & Policy Center: May 2018).

[59] Spiros Protopsaltis and Sharon Parrott, Pell Grants — a Key Tool for Expanding College Access and Economic Opportunity — Need Strengthening, Not Cuts (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities: July 27, 2017).

[60] Amy Rose, Barriers to Higher Education Attainment: Students’ Unmet Basic Needs (California Budget & Policy Center: May 2018).

[61] Mark Huelsman, et al., Less Debt, More Equity: Lowering Student Debt While Closing the Black-White Wealth Gap (Demos and Institute on Assets and Social Policy: 2015), pp. 16-17.

[62] Latinx students tend to borrow smaller amounts than both blacks and whites at public institutions but may borrow greater amounts at private for-profit institutions. See Mark Huelsman, The Debt Divide: The Racial and Class Bias Behind the “New Normal” of Student Borrowing (Demos: May 19, 2015), pp. 7-8.

[63] Mark Huelsman, The Debt Divide: The Racial and Class Bias Behind the “New Normal” of Student Borrowing (Demos: May 19, 2015), pp. 14-16.

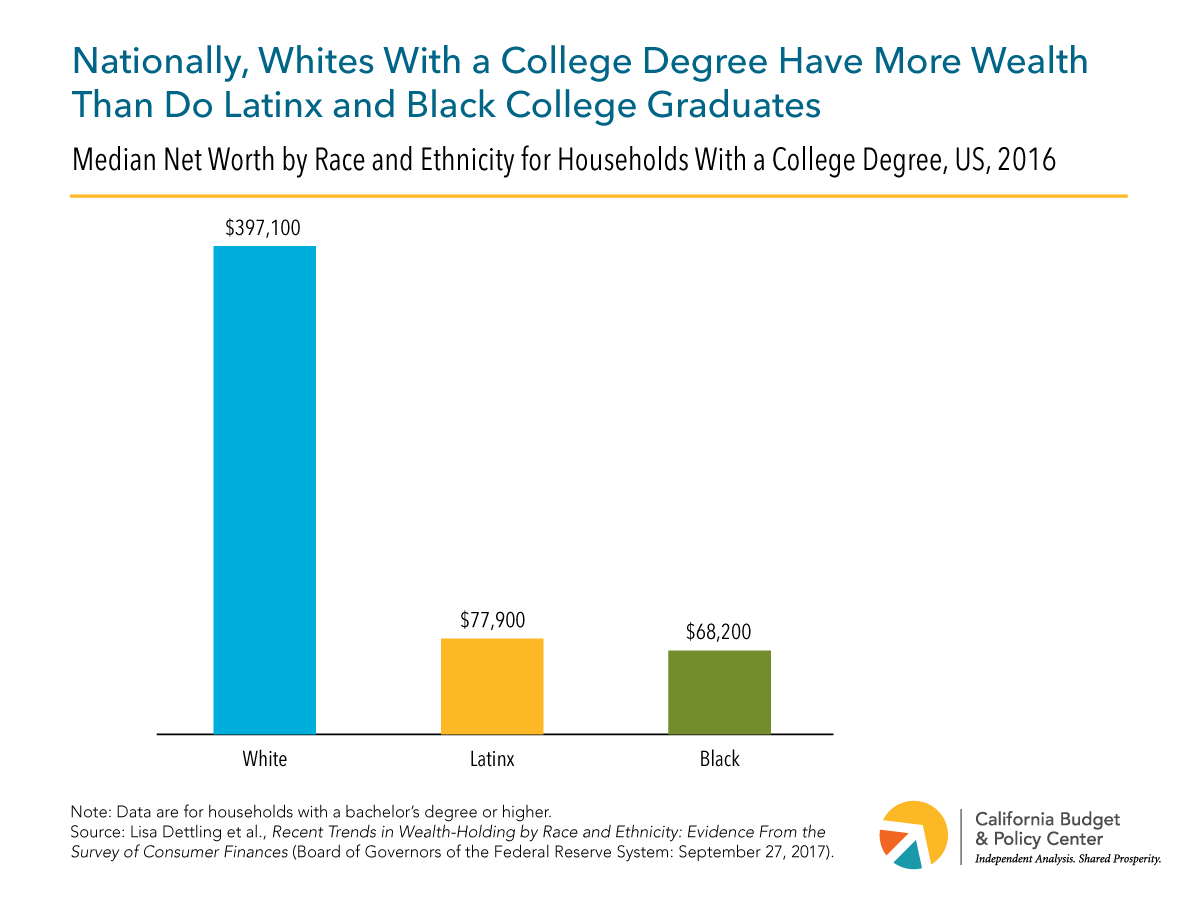

[64] For a white household whose head does not have a bachelor’s degree, median net worth is $98,100. For a black household whose head does have a college degree, median net worth is $68,200. For Latinx households, the equivalent figure is $77,900. See Lisa Dettling, et al., Recent Trends in Wealth-Holding by Race and Ethnicity: Evidence From the Survey of Consumer Finances (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System: September 27, 2017).

[65] Yunju Nam, et al., Bootstraps Are for Black Kids: Race, Wealth, and the Impact of Intergenerational Transfers on Adult Outcomes (The Insight Center for Community Economic Development: September 2015), p. 12.

[66] Jonathan Kaplan, Repeal of the Estate Tax Would Reduce Federal Resources While Key Public Services Are on the Chopping Block (California Budget & Policy Center: October 26, 2017).

[67] Even before the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, which further scaled back the national estate tax, only 2 out of every 1,000 estates were subject to the tax. Jonathan Kaplan, Repeal of the Estate Tax Would Reduce Federal Resources While Key Public Services Are on the Chopping Block (California Budget & Policy Center: October 26, 2017).

[68] Steven Bliss and Chris Hoene, Final GOP Tax Plan Is a Big Gift to the Wealthy, but Would Harm Most Households and Our Economy (California Budget & Policy Center: December 18, 2017).

[69] In order to establish a state estate tax, the Legislature would have to ask voters to repeal or amend Proposition 6 of 1982, which prohibits the state from imposing an estate, inheritance, or wealth tax. See California Budget & Policy Center, Principles and Policy: A Guide to California’s Tax System (April 2013), p. 21. For more information about state estate taxes, see Elizabeth McNichol, State Estate Taxes: A Key Tool for Broad Prosperity (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities: May 11, 2016).

[70] For estimates on the amount of revenue an estate tax could raise, see Elizabeth McNichol, State Estate Taxes: A Key Tool for Broad Prosperity (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities: May 11, 2016) and Legislative Analyst’s Office, A.G. File No. 2017-038 (November 30, 2017).

[71] Brett Theodos, et al., Affordable Homeownership: An Evaluation of Shared Equity Programs (Urban Institute: March 2017), p. 1.

[72] William Chen, Spending Through California’s Tax Code (California Budget & Policy Center: August 2016).

[73] In 2016, the average net housing wealth in the US was $215,800 for white homeowners versus $94,400 for black homeowners and $129,800 for Latinx homeowners. See Lisa Dettling, et al., Recent Trends in Wealth-Holding by Race and Ethnicity: Evidence From the Survey of Consumer Finances (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System: September 27, 2017).

[74] The Department of Finance estimates that California will lose $4 billion in revenue due to the mortgage interest deduction in state fiscal year 2018-19. See California Department of Finance, Tax Expenditure Report: 2018-19, p. 5.

[75] Mark Huelsman, et al., Less Debt, More Equity: Lowering Student Debt While Closing the Black-White Wealth Gap (Demos and Institute on Assets and Social Policy: 2015), pp. 18-20.

[76] Laura Sullivan,, et al., Equitable Investments in the Next Generation: Designing Policies to Close the Racial Wealth Gap (Institute on Assets and Social Policy and CFED: 2016), pp. 9-11.

[77] William H. Frey, The US Will Become “Minority White” in 2045, Census Projects (The Brookings Institution: Updated September 10, 2018).

[78] California Budget & Policy Center analysis of Department of Finance data.

[79] This report uses the terms “Asian” and “Asian American” depending on the cited source. For more on the SCF’s racial and ethnic categories, see Lisa Dettling, et al., Recent Trends in Wealth-Holding by Race and Ethnicity: Evidence From the Survey of Consumer Finances (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System: September 27, 2017).

[80] Melany De La Cruz-Viesca, et al., The Color of Wealth in Los Angeles (Duke University, The New School, the University of California, Los Angeles, and the Insight Center for Community Economic Development: March 2016), pp. 19-20.