As Californians scramble to submit their personal income tax returns before the Tax Day deadline, we at the Budget Center think this is the perfect time to take stock of how the state’s tax system performs on two key parameters: its ability to raise sufficient revenue to support public services, and how fairly it raises that revenue. Tax Day is also a chance to look forward and consider key opportunities for policymakers to more equitably raise revenue and support robust new investments that advance the health and well-being of all Californians, especially those who are struggling to make ends meet.

California Has Made Significant Strides Toward Tax Fairness in Recent Years, but There Is Room for More Progress

One key feature of a fair tax system is its progressivity — that is, the extent to which it asks taxpayers of different income levels to contribute taxes based on their ability to pay. According to this standard, higher-income taxpayers should pay more in taxes as a share of their incomes than lower-income taxpayers. In the years following the Great Recession and the state budget crisis, the state’s tax system has become fairer while raising significant revenues to fund new investments in California’s families and communities. This is thanks to both new Personal Income Tax (PIT) rates on high-income taxpayers and the creation and subsequent expansions of the California Earned Income Tax Credit (CalEITC), a refundable tax credit for working families with low incomes.

Proposition 30, approved by voters in 2012, temporarily created three new PIT rates affecting taxpayers with high incomes as well as a quarter-cent increase in the sales tax rate. With Proposition 55 in 2016, voters approved the extension of the higher PIT rates (but not the sales tax rate) through 2030. The increased PIT rates not only helped the state climb out of the budget crisis by bringing in new revenues, they have made the state’s tax code more progressive by asking Californians with a greater ability to pay to chip in more for state-provided resources that in many cases have helped high-income taxpayers to achieve their current economic success. These new income tax rates, which are almost exclusively paid by the richest 1%, contributed to the state’s ability to support new investments in K-12 education, child care and early learning, health coverage expansion, and retirement security.

The increased revenue from Prop. 30/Prop. 55 also helped make it possible to fund a state-level earned income tax credit, the CalEITC. The CalEITC was enacted in 2015 and expanded in the 2017-18 and 2018-19 budget agreements. By increasing the after-tax incomes of low-income working families, the CalEITC reduces economic hardship and can supplement other documented benefits of the federal Earned Income Tax Credit, such as enhancing children’s health and educational outcomes and increasing children’s future earnings capacity. Additionally, the CalEITC makes the state’s tax code more progressive by reducing the amount of income taxes lower-income families pay as a share of their income.

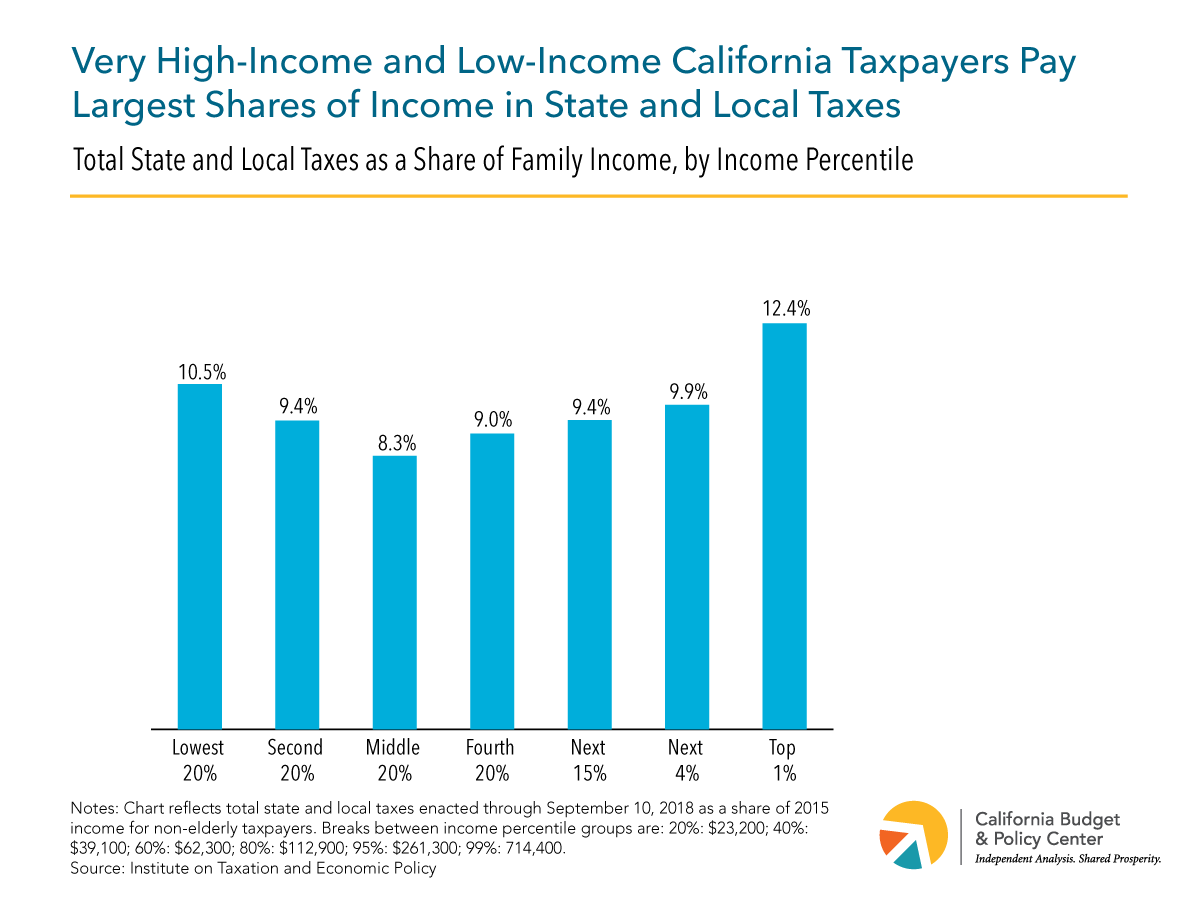

These tax policy choices are part of the reason that California’s tax code, unlike that of 45 other states, does not increase income inequality, according to data from the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP). Essentially, while most states have regressive tax systems that make incomes more unequal after taxes than they were before taxes, California’s system makes incomes more equal. In most states, low-income taxpayers pay a higher share of their income in state and local taxes (including income taxes, sales and excise taxes, and property taxes) than the highest-income taxpayers. In contrast, California’s richest 1% of taxpayers — those with incomes above $714,400 — pay a larger share of their income in taxes (12.4%) than any other income group, on average. This reflects the principle that taxpayers with the greatest resources are most able to contribute a larger share of their income.

However, California’s tax system is not perfectly progressive. The lowest-income group of taxpayers — those making less than $23,200 a year — pay a larger share of their income than all other income groups except the richest 1%. Clearly, it does not seem fair for taxpayers already struggling to make ends meet to have to dedicate a larger share of their modest incomes to taxes than better-off taxpayers. The primary reason for this is that state and local tax systems get significant revenues from sales and excise taxes, which make up a larger share of a lower-income household’s budget than a higher-income household’s budget. For instance, Californians with incomes below $23,300 pay 7.2% of their incomes in sales and excise taxes, compared to the richest 1%, who spend only 0.8% of their incomes on such taxes. While California is highly reliant on the PIT, a progressive revenue source, nearly 20% of the state’s General Fund revenues come from the sales and use tax, which hits low-income households the hardest.

Additionally, despite the previously mentioned accomplishments the state has made in past years, new investments are needed to meet the challenges facing the state, such as sustained poverty, high costs of living, an aging workforce, and uneven outcomes in health and educational attainment between income groups, racial and ethnic groups, and regions. This will require ongoing revenue sources, and the state should be careful to raise such revenue in a way that does not exacerbate income inequality.

A Near-Term Opportunity to Raise Revenue and Make the Tax Code Fairer

As part of the 2019-20 budget proposal, Governor Newsom offered up a plan to raise state tax revenues by adopting (or “conforming to”) a handful of reasonable provisions from the 2017 federal tax law and invest the new revenue into further expanding the CalEITC. As we previously noted, the state could raise an estimated $2.5 billion annually by adopting just five of these federal changes that limit existing tax breaks for corporations and businesses. Adopting three additional provisions limiting personal income tax breaks that benefit higher-income taxpayers more than lower-income taxpayers — the mortgage interest deduction, the local property tax deduction, and miscellaneous itemized deductions — could raise another $1.9 billion.

The Governor proposed a package of federal tax conformity provisions that would raise enough revenue to fully cover the cost of the CalEITC, including the proposed expansions to the credit. These expansions would extend the credit to an estimated 1 million additional tax filers and increase the size of the credit for those who currently only qualify for small credits. Additionally, filers with children under 6 and incomes under $28,000 would be eligible for an additional $500. Together, these expansions would increase the cost of the CalEITC from around $400 million to $1 billion.

The Governor’s proposal is a key opportunity for lawmakers to make the tax code more fair. The limitations on corporate and business tax breaks would mostly affect higher-income taxpayers, who derive larger shares of their incomes from business-related sources, such as capital gains and dividends from holding corporate stock, or investments in a partnership or other business entity. California taxpayers in the bottom 95% of the income distribution get nearly four-fifths of their income (78.7%) from wages and only 8% from business and investment sources other than retirement accounts, according to Franchise Tax Board data. In contrast, the top 5% of California taxpayers — those making over $230,223 — get over two-fifths (43.8%) of their income from business and investment sources and just over half from wages (52.9%). If the revenues raised from the proposed limitations to corporate/business tax breaks are specifically earmarked for the CalEITC expansion, they would exclusively benefit taxpayers with incomes of $30,000 or less (the new income limit for households of all sizes proposed in the Governor’s budget.)

Since the Governor’s proposed tax conformity package would pay for the entire cost of the CalEITC and not just the increased cost, it would free up space in the state’s General Fund to help support other priorities for low- and middle-income families. Additionally, given that there is significantly more than $1 billion in potential revenues to raise by selectively conforming to the federal tax law, legislators could choose to go beyond the Governor’s proposal and raise enough revenue for the expanded CalEITC and other new investments. Beyond making the tax system fairer, such a conformity package could increase support for not only the CalEITC but also education, housing, health care, and other economic security programs, all of which can contribute to improved health and well-being for California residents.

Additional Options to Raise Revenues and Reduce Income Inequality

The tax conformity/CalEITC package is just one of the many possibilities to strengthen California’s ability to fund essential state services and lay a foundation for bold new investments in shared prosperity without making the state’s tax system less progressive. For example, policymakers could undertake a comprehensive review of the state’s arcane collection of tax expenditures (such as credits, deductions, and income exclusions) and eliminate or restructure those that primarily benefit more well-off households and corporations. One positive step would be to better target those personal income tax expenditures that are deemed to have reasonable policy goals — for instance, by capping or phasing out tax breaks for high-income taxpayers and converting some tax deductions into refundable credits that would benefit low-income households. Another would be to eliminate those corporate tax expenditures that mostly benefit large corporations while having questionable effects on the state’s economy. Wealth inequality is even more severe than income inequality, and lawmakers could also consider ideas to more adequately tax wealth — such as reinstating a state-level estate or inheritance tax or looking at options for a tax on net worth. These taxes could be structured to only affect the wealthiest taxpayers, and would offset the trend of increased concentration of wealth among those at the top, which perpetuates barriers to opportunity for households less likely to have the benefit of inherited wealth, including people of color. These are just a few of the options policymakers have to continue working toward a more equitable tax system that provides the resources to help all Californians thrive.

— Kayla Kitson