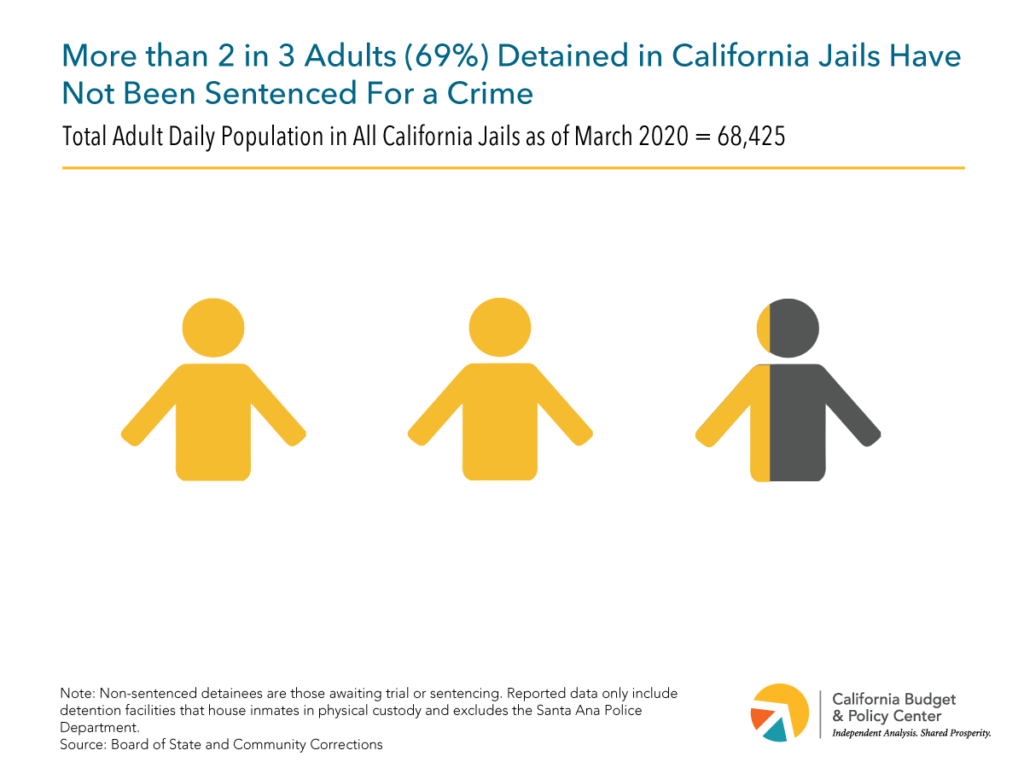

Across California and the United States, the push for bail reform has gained momentum with increasing awareness and research showing the disproportionate impact the money bail system has on people of color and low-income households. In California, it’s estimated over two-thirds of people detained in jails – around 47,000 – have not been sentenced for a crime, a number that includes both those who cannot afford bail and those who are awaiting sentencing post-conviction (Fig. 1).1These numbers reflect the unsentenced adult daily population in all California jails. Counties are not asked to report the number of unsentenced defendants who remain in custody because they cannot afford to post bail . Board of State and Community Corrections, Jail Population Survey. Data reflect the average daily jail population as of March 2020. https://public.tableau.com/profile/kstevens#!/vizhome/ACJROctober2013/About Los Angeles County alone is the largest jail system in the US and houses over 1 in 5 of adults who have not been sentenced for an alleged crime in California.

Enter Proposition 25 that will appear on the November 3, 2020 statewide ballot and asks California voters to decide whether a 2018 state law that effectively ends money bail should take effect. If voters approve Prop. 25, judges will be able to utilize risk-based assessment tools – examining population links between rearrest or reconviction and individual factors such as age, gender, or criminal record – to determine if individuals detained for certain crimes can be released before a court appearance rather than posting money bail.

how does money bail work in california?

Bail is the process of securing release for an arrested person who a judge has decided may be released from jail pending any court hearings. While some people are released without financial conditions, many others will only go free if they pay either the courts or a bail bond agent first. This payment is referred to as money bail.

Efforts to reform California’s bail system also aim to address the wide racial disparities seen in the criminal justice system. In part, these disparities stem from structural racism that exacerbate the disproportionate level of policing and arrests faced by communities of color. Black Californians currently face higher arrest rates than white Californians in most counties throughout the state, with the wealthiest counties having the largest gaps.2Magnus Lofstrom et al., Racial Disparities in California Arrests (Public Policy Institute of California: October 2019). Nationally, Black and Latinx defendants are also more likely to be held in pretrial custody and have bail set at a higher amount than white defendants.3Wendy Sawyer, How Race Impacts Who is Detained Pretrial (Prison Policy Initiative: October 19, 2019). With the state’s median bail amount ($50,000) five times higher than the rest of the country (less than $10,000), money bail is particularly costly for Californians compared to residents in other states.4Soyna Tafoya, Pretrial Detention and Jail Capacity in California (Public Policy Institute of California: July 2015), p.4. Additional racial, economic, and gender disparities embedded in the money bail system are discussed in this report.

| Types of Money Bail | Description | Financial Liability |

|---|---|---|

| Commercial bail bond | The defendant pays the bail bond agent a fee, which is usually 10% of the value of the bond. Bail agents may also require collateral. Family and friends may co-sign the bond and pay on behalf of the defendant. This is the primary way of paying money bail to secure a defendant’s release.5Pretrial Detention Reform Workgroup, Pretrial Detention Reform: Recommendations to the Chief Justice (October 2017), p. 29. | If defendants fail to appear, the bond agent may forfeit the full bail amount, which agents can seek to reclaim from the defendant’s family and friends.6In reality, due to forfeiture laws, bail bond agents rarely forfeit the full bail amount if a defendant fails to appear. See Pretrial Detention Reform Workgroup, Pretrial Detention Reform: Recommendations to the Chief Justice (October 2017), p. 37. The fee is nonrefundable, even if the defendant makes all of their required court appearances and no matter what happens with the case. |

| Cash | Defendants, their family, and/or friends pay bail directly to the court, either with cash or its equivalent, such as a check or money order. | If defendants fail to appear, they are liable for the full bail amount. If a defendant is convicted, some or all of the cash bond is put toward restitution costs. Otherwise, the cash bond is refunded to the defendant at the conclusion.7The defendant receives the full amount of the cash bond less any additional fines, fees, or processing costs the court may charge. However, if the defendant is convicted, the value of the cash bond may go toward restitution. See Pretrial Detention Reform Workgroup, Pretrial Detention Reform: Recommendations to the Chief Justice (October 2017), p. 30. |

| Property bond | Defendants, their family and/or friends, may post real property as collateral instead of a cash deposit.8The property can be accepted as bail if the court determines that the equity in the property is twice the value of the bail amount. See Pretrial Detention Reform Workgroup, Pretrial Detention Reform: Recommendations to the Chief Justice (October 2017), p. 31. | If defendants fail to appear, they, or their family and friends, must forfeit the property. |

What is California’s Bail Reform Law and Why is it on the 2020 Ballot?

In 2018, state legislators passed a bail reform law called Senate Bill 10 (SB 10), which former Governor Jerry Brown signed.9SB 10 (Hertzberg, Chapter 244 of 2018). SB 10 was the culmination of various efforts to replace money bail in California with a non-monetary pretrial system. The primary purpose of the law is to eliminate the money bail system and ensure that if a Californian is awaiting hearings or trial, they are not held in jail because they cannot afford to pay bail (or to pay a bail bond agent’s fee).10Under the law, if someone were accused of committing a misdemeanor, they would be automatically released, though there are some exceptions, including violations of protective orders, among others. See SB 10 (Hertzberg, Chapter 244 of 2018). To determine who should still be detained, courts would use risk assessment tools, which are intended to predict the chance that someone might not appear for a hearing date or might be rearrested before trial.11Risk-based assessments are typically generated by statistically analyzing large data sets to identify links between rearrest or reconviction and other factors such as age, gender, or criminal record. See Megan T. Stevenson, “Assessing Risk Assessment in Action,” Minnesota Law Review 103:1 (2018), p. 304.

Shortly after the law passed, the American Bail Coalition spearheaded a challenge through a veto referendum petition to place the law on the ballot.

Under Prop. 25, California voters are asked to decide in November 2020 if they want to uphold the bail reform law or if they want to repeal it. A YES vote on Prop. 25 would allow SB 10 to take effect, effectively ending the state’s money bail system. A NO vote on Prop. 25 would repeal SB 10 and keep the current money bail system in place.

Equity and Safety Concerns about Money Bail

As California, local jurisdictions, and many states examine public safety priorities, and in light of Black and brown communities calling for justice from police and sheriff departments along with courts, many questions are raised about the economic, racial and gender implications of money bail. This also leads to questions about the role money bail plays in deterring criminal activity and accountability for individuals.

Is money bail unfair to low-income Californians?

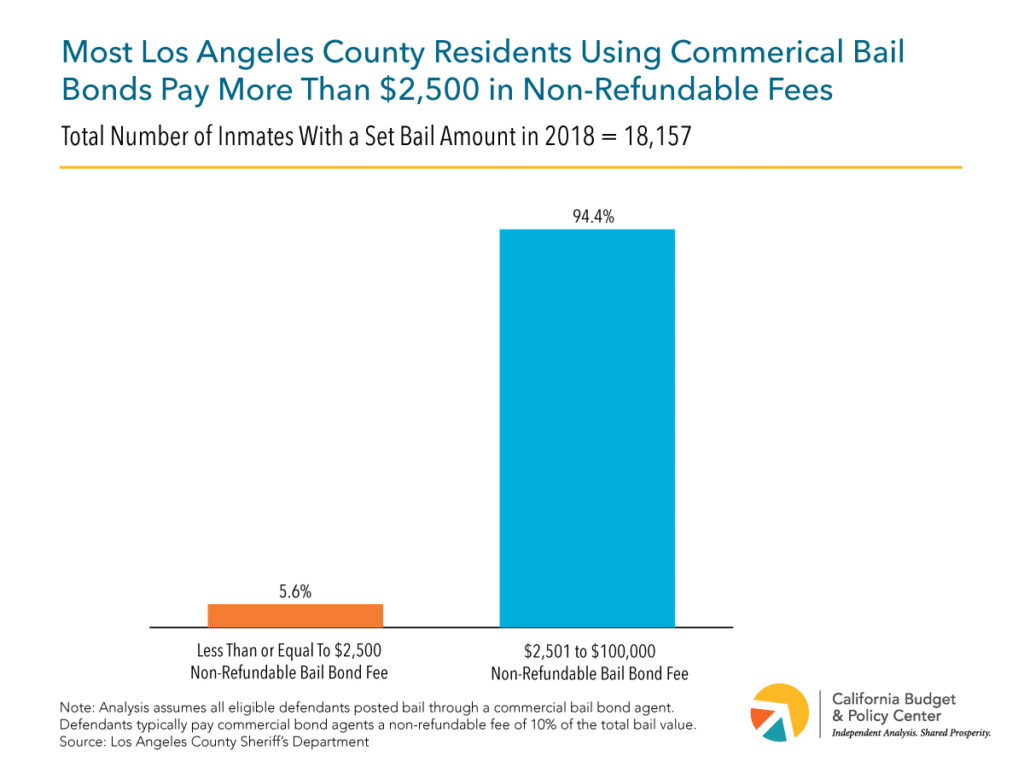

Requiring people pay bail to secure their freedom before trial disproportionately impacts Californians with low incomes. In 2009, the most recent year for which data are available, the median bail amount in California was $50,000.12Sonya Tafoya, Pretrial Detention and Jail Capacity in California, (Public Policy Institute of California: July 2015). Considering median annual household income in 2010 was about $57,700, bail was – and continues to be – set higher than many Californians can afford.13US Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2010 1-Year Estimates. Table S1903: Median Income in the Past 12 Months (In 2010 Inflation-Adjusted Dollars), downloaded from https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?t=Income%20%28Households,%20Families,%20Individuals%29&g=0400000US06&y=2010&tid=ACSST1Y2010.S1903&hidePreview=true on August 24, 2020.Though the Eighth Amendment protects against “excessive” bail, the Supreme Court has ruled that bail may only be considered excessive if it is more than necessary to achieve the court’s goals, not if bail is more than a person can pay. The court found that “[t]he plain meaning of ‘excessive bail’ does not require that it be beyond one’s means, only that it be greater than necessary to achieve the purposes for which bail is imposed.” See Pretrial Detention Reform Workgroup, Pretrial Detention Reform: Recommendations to the Chief Justice (October 2017), p. 73. In the majority of cases, Californians must contract with a commercial bail bond agent who posts bail for them.14In Los Angeles County, San Francisco County, and Santa Clara County, commercial bail bonds were the primary means of posting bail. In one year, cash bonds were used in less than 2% of total cases, followed by property bonds (less than 1%). See Pretrial Detention Reform Workgroup, Pretrial Detention Reform: Recommendations to the Chief Justice (October 2017), p. 31. Additionally, in 2017, 99.9% of people who posted bail in the city of Los Angeles did so through a commercial bail bond agent. See Isaac Bryan, et. al, The Price of Freedom: Bail in the City of Los Angeles (UCLA Bunche Center for African-American Studies and Million Dollar Hoods: May 2018). In turn, the person has to pay a premium (often 10% of the total bail amount) that is nonrefundable, even if the prosecutor never files charges or if the person is ultimately acquitted.15The defendant (or their family members and friends) may also face extra costs, such as late payment fees and interest on the premium. See The UCLA School of Law Criminal Justice Reform Clinic, The Devil is in the Details: Bail Bond Contracts in California (May 2017), p. 15. Moreover, as just under 4 in 10 Americans (37%) cannot easily cover an unexpected expense of $400, even this fee could be out of reach of many.16Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Report on the Economic Well-Beingof U.S. Households in 2019, Featuring Supplemental Data from April 2020 (May 2020). For example, in 2018 in Los Angeles County, assuming everyone eligible for bail turned to a commercial bail bond agent, 95% of people would have had to pay fees ranging from $2,501 to $100,000 (Fig. 2).17Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, Custody Division Population Year End Review, p. 30. With this money bail system, many may simply be unable to pay. In 2017, the majority of bail (81.6%) levied in the city of Los Angeles actually went unpaid and people stayed in jail, either because they could not pay or chose not to.18Isaac Bryan, et. al, The Price of Freedom: Bail in the City of Los Angeles (UCLA Bunche Center for African-American Studies and Million Dollar Hoods: May 2018).

Does money bail reflect and exacerbate racial and gender inequities?

Due to ongoing over-policing and discrimination, Black and Latinx Californians are disproportionately arrested and detained, and thus are more likely to have to pay bail.19Magnus Lofstrom, et. al., Racial Disparities in California Arrests (Public Policy Institute of California: October 2019) and Pranita Amatya, et. al., Bail Reform in California (UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs: May 2017), p. 27. In Los Angeles, Latinx residents paid nearly half (48%) of all non-refundable bail bond deposits, and Black residents paid a quarter (25%).20Isaac Bryan, et. al, The Price of Freedom: Bail in the City of Los Angeles (UCLA Bunche Center for African-American Studies and Million Dollar Hoods: May 2018). Latinx and Black families are less likely to have the means to weather such financial setbacks, as they have less wealth.21Esi Hutchful, The Racial Wealth Gap: What California Can Do About a Long-Standing Obstacle to Shared Prosperity (California Budget & Policy Center: December 2018). Money bail may also particularly harm women, who tend to be less likely to afford bail themselves and who are most likely to bear the financial burden of bail and other fees when family members are incarcerated.22Ella Baker Center for Human Rights, Forward Together, and Research Action Design, Who Pays?: The True Cost of Incarceration on Families (September 2015) and Leon Digard and Elizabeth Swavola, Justice Denied: The Harmful and Lasting Effects of Pretrial Detention (Vera Institute of Justice: April 2019), p. 7. In San Francisco County, for example, most co-signers of commercial bail bonds are women.23Pretrial Detention Reform Workgroup, Pretrial Detention Reform: Recommendations to the Chief Justice (October 2017), p. 39.

Does money bail deter criminal activity?

One of the common justifications of bail is that it upholds public safety by keeping people who could be dangerous in jail or by discouraging a released person from committing a crime as they await their court hearings.24Judicial Council of California, Bail in California: Legal Framework (February 19, 2016). However, there is no evidence that money bail serves either purpose. Currently, people who are eligible for bail yet remain detained have already been deemed by a judge to be safe enough for release. They only remain in jail because they cannot or have not paid, not because they are a greater safety risk than those who managed to pay. Moreover, money bail may not provide a strong financial deterrent to future offenses. When a person is released on bail, they do not forfeit the total bail amount they paid if they are accused of committing a new offense; they only forfeit bail when they fail to appear for their hearing.25Curtis E. Karnow, “Setting Bail for Public Safety,” Berkeley Journal of Criminal Law 13:1 (2008), p. 20. As a result, there is not a direct link between a defendant allegedly committing a new crime and forfeiting bail.

Does money bail ensure court appearances?

The evidence suggests that the threat of bail forfeitures in the event of failure to appear does not effectively ensure appearances. For those who use a commercial bail bond to pay for their pretrial release, the fee they pay to the bail agency is nonrefundable whether they later show up to court or not. For those who pay their own bail, the threat of forfeiture is not the determining factor in if people appear. Research suggests failure to appear may be more indicative of personal circumstances and, potentially, the length of pretrial detainment.26While a frequently cited study conducted in Kentucky found pretrial detention increased a defendant’s likelihood to fail to appear for court, these results have not been replicated. A growing body of evidence actually hints that pretrial detention reduces failure to appear rates. Léon Digard and Elizabeth Swavola, Justice Denied: The Harmful and Lasting Effects of Pretrial Detention (Vera Institute of Justice: April 2019), p.3. Generally, very few people released pretrial purposefully miss their court dates, and those who do miss them eventually appear for court on their own. If a person does fail to appear, it is often attributed to lack of child care, work, homelessness, disability due to a serious mental illness, negligence, or error.27Human Rights Watch, “Not in it for Justice:” How California’s Pretrial Detention and Bail System Unfairly Punishes Poor People (April 11, 2017), p.7.

Some suggest that because the bail bond agents are financially liable if a person does not show, they are encouraged to ensure an appearance. However, there is no strong evidence supporting the notion that bail bond agents in California directly ensure a defendant appears for court.28Pretrial Detention Reform Workgroup, Pretrial Detention Reform: Recommendations to the Chief Justice (October 2017), p. 36. Studies conducted in San Francisco and Santa Clara County found that although bail bond agents are responsible for a defendant, the responsibility often falls on the county to provide pretrial supervision and recover fugitives who are in custody.29Pretrial Detention Reform Workgroup, Pretrial Detention Reform: Recommendations to the Chief Justice (October 2017), pp. 39-41. Moreover, if a defendant does not appear for their hearing, it is rare for bail bond agents to pay the total remaining bail amount because of strict and costly forfeiture laws courts must follow to receive full payment.30Pretrial Detention Reform Workgroup, Pretrial Detention Reform: Recommendations to the Chief Justice (October 2017), p. 37.

Equity and Safety Concerns about Pretrial Detention

As the equity and public safety concerns are weighed about reforming bail in California, this option also brings up questions about pretrial detention, which Prop. 25 does not end. It is important to understand the economic and public safety aspects of pretrial detention for Californians held in jail, their families, and the larger community.

Does pretrial detention unfairly punish people and their families?

While someone is in jail, they lose their freedom, are unable to go to work, are unable to care for their children and other dependent family members, and risk losing their housing.31Shima Baradaran Baughman, “Costs of Pretrial Detention,” Boston University Law Review 97:1 (2017) p. 5. Detention can therefore be regarded as a way of punishing people who have not even had their day in court. Detention can also have further implications for a person’s case. Research indicates that when compared to similar defendants who are released, those who remain detained are more likely to plead guilty, to be convicted, and to receive harsher sentences.32United States Department of Justice, National Institute of Corrections, “Pretrial,” accessed at https://nicic.gov/pretrial on July 6, 2020 and Leon Digard and Elizabeth Swavola, Justice Denied: The Harmful and Lasting Effects of Pretrial Detention (Vera Institute of Justice: April 2019), pp. 3-5. Results of a study of one Texas county suggested that 17% of jailed residents who pleaded guilty would not have been convicted at all if they had been released pretrial, suggesting that they may have pleaded guilty just to secure their release.33Data reflect misdemeanor defendants. In the study, detention increased the likelihood of pleading guilty by 25%. Paul Heaton, Sandra G. Mayson, and Megan Stevenson, “The Downstream Consequences of Misdemeanor Pretrial Detention” Stanford Law Review 69:3 (2017), p. 771. Californians and their families–particularly those who are Black, Latinx, or who have low incomes– bear these costs irrespective of whether they are ultimately acquitted, convicted, or their charges are dismissed.

Does detention raise public safety concerns?

Research shows that even short periods of pretrial detention will increase an individual’s risk of allegedly committing more crimes, not reduce it. A study conducted in Harris County, Texas, the fourth largest county in the US, found pretrial custody was associated with a 20% increase in new misdemeanor charges and a 30% increase in new felony charges 18 months after a defendant’s initial post-bail hearing.34Paul Heaton, Sandra G. Mayson, and Megan Stevenson, “The Downstream Consequences of Misdemeanor Pretrial Detention” Stanford Law Review 69:3 (2017), p. 718. In California, research found that large urban areas which heavily rely on pretrial detention experienced higher rates of failure to appear in court and higher levels of felony arrests during a defendant’s pretrial period, compared to other urban areas nationally which did not heavily rely on pretrial detention.35Sonya Tafoya et al., Pretrial Release in California (Public Policy Institute of California: May 2017), p. 5. These findings suggest that the use of money bail acts as a deterrent to public safety and ultimately contributes to outcomes that come at a greater cost to society and leads to more incarceration. And while opponents of bail reform also point to increasing levels of offenses in New York that implemented bail reform similar to risk-assessments, these statistics have been criticized because of the short analysis period and potential data manipulation.36The New York state legislature has since amended their bail reform law with a number of changes that took effect in July. See Jamiles Lartey, New York Rolled Back Bail Reform. What Will the Rest of the Country Do? (The Marshall Project: April 23, 2020).

Equity and Safety Concerns about Risk Assessments

Providing a judge with more information about a Californian who has been arrested, assessing whether the individual is a risk to the community, and determining if the person should be freed without paying bail until the next decision in a case – this is the essence of risk assessment tools and Prop. 25. Risk assessment tools, as many parts of Californian’s vast criminal justice and public safety system, bring up concerns about racial, gender, and socioeconomic disparities.

Can risk assessment tools effectively predict criminal activity or likelihood to appear?

Under the existing cash bail system, when judges set a bail amount, they are intended to base their decision on the severity of the alleged offense, their estimate of a person’s probability to reoffend and flight risk. As California’s bail reform law eliminates bail, courts would have to focus more of their efforts on deciding who to detain. As written, the law specifically instructs courts to use “accurate and reliable” risk assessment tools to help make these decisions.37SB 10 (Hertzberg, Chapter 244 of 2018). Proponents of these tools argue that they will prevent judges from making subjective error-prone determinations.38Megan T. Stevenson, “Assessing Risk Assessment in Action,” Minnesota Law Review 103:1 (2018). p. 305. However, evidence of the effectiveness of pretrial risk assessments is unclear. While in theory such algorithm-based assessments could be effective at predicting who is likely to miss court appearances or to be rearrested, their impact depends highly on the design and underlying assumptions, as well as on how these tools are implemented.39Megan T. Stevenson, “Assessing Risk Assessment in Action,” Minnesota Law Review 103:1 (2018). pp. 306-307, 310-11, 327. Additionally, depending on the tool, the data it relies on, and the people interpreting it, pretrial risk assessments may have built-in racial and implicit biases.

Can risk-based assessments contribute to disparities in the criminal justice system?

Risk-based assessment tools could also exacerbate racial, gender, and socioeconomic disparities in the criminal justice system. This is because risk-based assessment algorithms incorporate existing criminal justice data, which reflect that communities of color are often overpoliced. Therefore, defendants who reside in communities that have high levels of crime are more likely to be considered “high risk” because of where they live than those who live in more affluent neighborhoods. However, research also shows that defendants detained in jail while awaiting trial are more likely to plead guilty, be convicted, be sentenced to prison, and receive harsher sentences than similar defendants who are released during the pretrial period. Given that people of color and those with low incomes are the majority of individuals overpoliced and arrested, the current money-based pretrial detention system also drives these gaps.

A Brief History of Bail

Today, bail is commonly understood as the amount of money someone must pay to get out of jail. However, originally bail simply meant “the right to release before trial.” This meaning has its roots in early England, where the courts differentiated between offenses that would allow for release before trial (bailable) and those that mandated detention until trial (non-bailable). If an accused person was released, a friend or family member would act as a “personal surety” and pledge to pay money if the accused did not appear in court. Critically, payment only occurred as a consequence for failure to appear and the personal surety was not allowed to profit.40Timothy R. Schnacke, “A Brief History of Bail,” The Judges’ Journal 57 (2018) and Timothy R. Schnacke, Money as a Criminal Justice Stakeholder: The Judge’s Decision to Release or Detain a Defendant Pretrial (National Institute of Corrections: September 2014).

Though these practices were carried over to the American colonies, in the 1800s this system underwent several key changes making money more important to release. As personal sureties became scarce, commercial bail emerged in the late 1800s, with bail bond agents acting as sureties who could profit if they paid the defendant’s behalf. With the exception of the Philippines, the United States stands alone in its widespread embrace of the practice of commercial bail.41Timothy R. Schnacke, Money as a Criminal Justice Stakeholder: The Judge’s Decision to Release or Detain a Defendant Pretrial (National Institute of Corrections: September 2014), p. 26. Bail thus became an upfront deposit as a condition of release, instead of a payment only as a consequence for failure to appear. These changes increased the chances that a defendant could be eligible for release and yet still remain detained due to inability to pay.

Today, payment and release are so intertwined that “money bail” has become synonymous with release outright. In California, bail bonds are primarily posted through commercial bail agents, instead of directly by the arrested person.