Proposition 10, which will appear on the November 6, 2018 statewide ballot, would repeal a state law that limits the scope of local rent control policies that cities and other local jurisdictions are allowed to adopt. Prop. 10 was placed on the ballot by petition signatures and qualified for the ballot with key financial support from Michael Weinstein of the AIDS Healthcare Foundation. This post provides an overview of Prop. 10, discusses its expected impact, and examines other issues the measure raises in order to help voters reach an informed decision.

What Would Proposition 10 Do?

Prop. 10 would repeal a state law, the Costa-Hawkins Rental Housing Act (or “Costa-Hawkins”), that currently places restrictions on the rent control policies that cities and other local jurisdictions may choose to apply to rental housing in order to limit allowed rent increases. Costa-Hawkins currently prohibits cities from limiting rent increases in certain types of rental homes, including single-family homes, apartments that were built after February 1995 (or after an earlier date in some cities), and vacant apartments that are turning over to new tenants. By repealing Costa-Hawkins, Prop. 10 would allow cities to choose to limit rent increases in these types of rental homes in addition to the older, occupied rental apartments to which local jurisdictions may currently apply rent control if they choose.[1]

What Problem Does Proposition 10 Aim to Address?

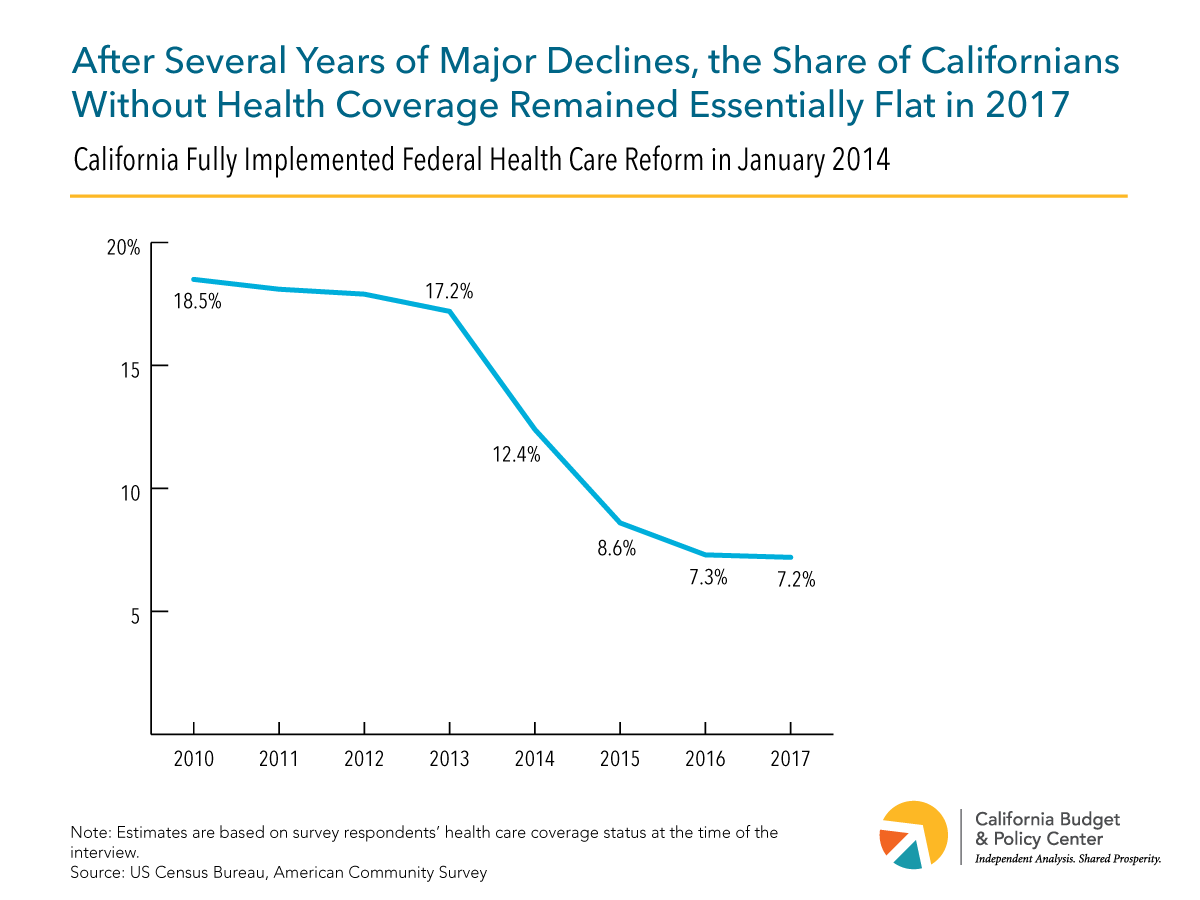

Housing costs in many parts of California are very high, and housing is unaffordable for many residents in all parts of the state.[2] [3] Many Californians now pay more than 30% of their income for housing, which the US Department of Housing and Urban Development defines as an unaffordable housing cost burden. Among all Californians in 2016, more than 4 in 10 households across the state were housing cost-burdened, and more than 1 in 5 were severely cost-burdened, spending over half their incomes on housing, according to a Budget Center analysis of US Census Bureau data. Unaffordable housing is a problem that disproportionately affects low-income households, and the majority of individuals with high housing cost burdens in California are people of color.[4] Moreover, California renters are particularly affected by unaffordable housing cost burdens. More than half of California renter households paid over 30% of their income toward housing in 2016, and nearly 1 in 3 paid more than half of their incomes toward housing (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

These high housing cost burdens have serious consequences for California families. By making it harder for families to make ends meet, unaffordable housing costs may force families to double-up to save on rent or settle for substandard housing in unhealthy, low-opportunity neighborhoods. Families who are paying more than they can afford for housing may have to cut costs by choosing low-quality child care or letting health problems go unaddressed, and they may be unable to set aside savings for emergencies or for retirement. In the worst cases, they may be pushed into homelessness. These kinds of hardships have both immediate and long-term consequences, for adults and especially for children.[5]

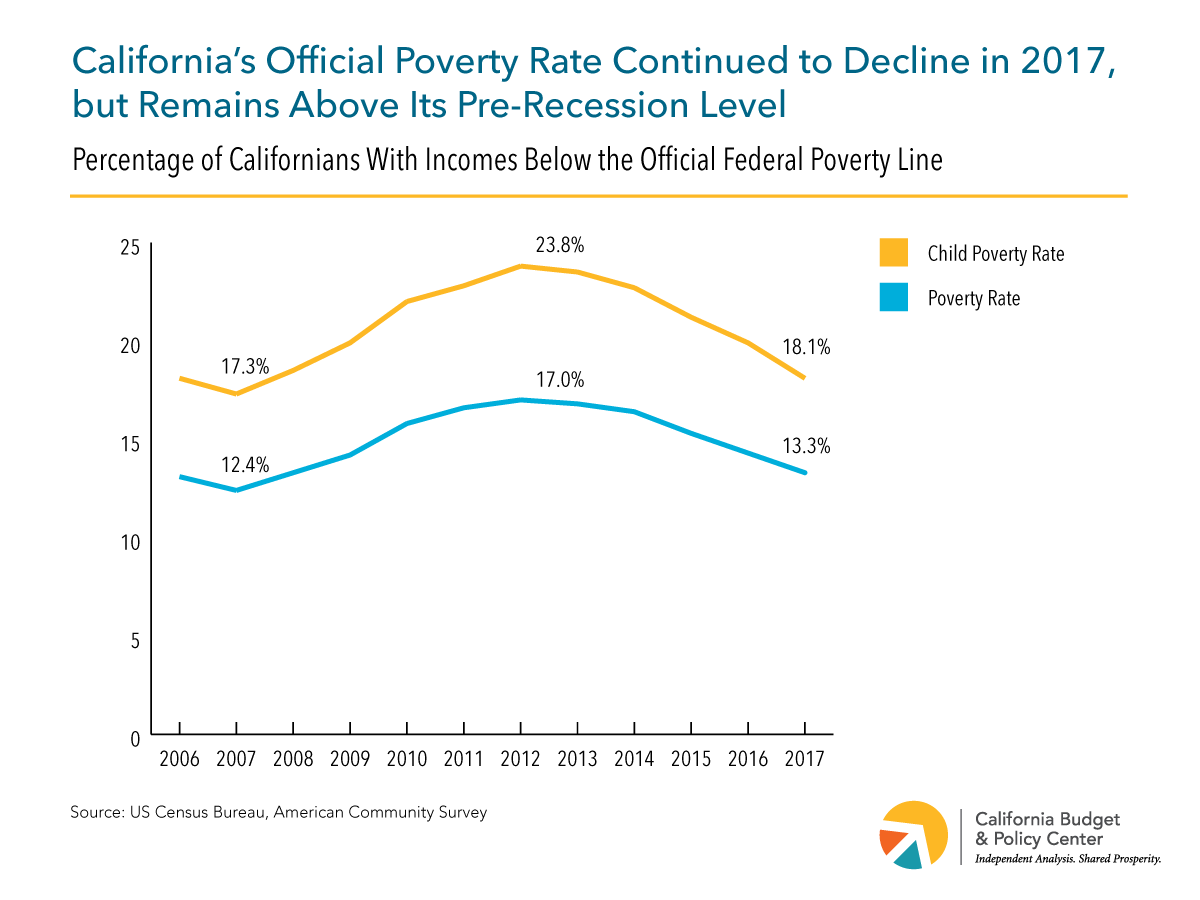

California’s unaffordable housing costs are a problem not simply because housing costs are high, but because they have been growing quickly relative to incomes. While median annual earnings for full-time workers in California increased 4% from 2006 to 2016, median household rents increased by 13%, more than three times as much as earnings did, during the same period (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

With earnings outpaced by living costs, families and single individuals struggle to cover the basic costs of housing, food, child care, and other needs. As a response to California’s housing pressures, rent control focuses on protecting renters from rapidly rising housing costs. Prop. 10 would allow cities to choose to expand local rent controls by repealing the restrictions on rent control imposed by Costa-Hawkins.

What Is the History of the Costa-Hawkins Rental Housing Act?

In the 1970s and 1980s, an earlier period of rapidly rising rents, several California cities adopted local policies that limited the rent increases that landlords were allowed to impose, policies known as rent control or rent stabilization. Landlords and housing developers sought to restrict the allowed scope of these types of local policies through a failed state ballot initiative and repeated failed legislative proposals in the 1970s, 1980s, and early 1990s. Finally, in 1995, the Costa-Hawkins Rental Housing Act, sponsored by the California real estate industry, passed the Legislature and was signed by Governor Pete Wilson.[6]

Through Costa-Hawkins, the state imposed three limits on the scope of local rent control laws.[7] First, single-family homes were exempted from rent control. Secondly, rent control could not apply to any newly built housing starting February 1, 1995. For cities that already had some form of rent control, Costa-Hawkins back-dated this second restriction on rent controls on new housing to the date of the local ordinance. (For example, since Los Angeles instituted rent control in 1978, housing built after 1978 in Los Angeles was required to be exempt from rent control.) Finally, the Act prohibited local jurisdictions from imposing “vacancy control,” or requiring that below-market rents be maintained on rent-controlled apartments even after tenant turnover. In other words, Costa-Hawkins required that landlords of rent-controlled buildings be allowed to charge market-rate rent to new tenants moving into a unit that had been vacated (known as “vacancy de-control”). By repealing Costa-Hawkins, Prop. 10 would remove these three restrictions on the rent control policies that local jurisdictions are allowed to adopt.

What Is the Expected Impact of Proposition 10?

First, it is important to note what Prop. 10 would not do. Prop. 10 would not establish the basic authority of cities in California to choose to adopt rent control policies that apply to a substantial share of rental housing in the state. Local jurisdictions are already permitted to limit rent increases in all housing that is not explicitly exempted from rent control by Costa-Hawkins, and the older apartments that are not covered by Costa-Hawkins make up roughly half of all existing rental homes in California. In fact, most recently — in 2016 — voters in two San Francisco Bay Area cities approved new policies to establish local rent controls for the first time, to apply to rental apartments built before February 1995.[8] Moreover, if Prop. 10 passes, rent controls would not automatically be expanded to additional cities or (with a few exceptions) to additional rental homes in California.[9] In nearly all cases, cities or other local jurisdictions would have to take separate action, through their elected officials or voter initiatives, to adopt new local rent stabilization policies that would apply to the types of housing that are currently exempt from rent limits under Costa-Hawkins. Prop. 10 also would not force landlords to rent out units at a loss, since state law would continue to require that local rent control policies allow landlords to receive a “fair rate of return.”[10]

What Prop. 10 would do is allow cities to choose to limit rent increases within a broader range of rental homes, including single-family homes and apartments built since 1995 (or since earlier years in cities with longer-standing rent control policies) and/or when new tenants move into a vacant rental home. Cities that already have rent control policies in place (see Table 1) could choose to expand these policies to cover more of their rental stock or to restrict rent increases when a unit becomes vacant. Cities that do not currently have rent control policies could choose to adopt new policies that would apply to all of their rental housing or to any subset of rental homes without regard to the limitations currently set by Costa-Hawkins. For example, a city could choose to adopt new rent controls that would apply to all rental homes, or to all apartments built before 2005 but only for continuing tenants, or to both single-family homes and apartments built before 1995 but only for landlords that rent out at least 25 homes, or to any other subset of rental homes. Existing local rent control ordinances vary greatly in how they are designed, and any new local ordinances would likely also show considerable variation.

Table 1

While a large share of rental homes in California are not required to be exempt from rent control by Costa-Hawkins, a significant number of renters live in properties that could become newly covered by rent controls if Prop. 10 passes and their local jurisdiction chooses to adopt new rent control policies that apply to these homes. Statewide, more than one-third (35.5%) of renter households — or 2.06 million households — lived in single-family homes as of 2016, and this share has increased by about 10% since 2006, when 32.4% of renter households lived in single-family homes.[11] Renter households are most likely to live in single-family homes in the less urban, inland regions of the state — for example, more than half of renter households in the Sierra Nevada (55.4%), Central Valley (53.0%) and Far North (51.4%) lived in single-family homes in 2015-2016. Renters are least likely to live in single-family homes in the coastal urban regions of California — for example, in 2015-2016 less than a third of renter households occupied single-family homes in Los Angeles and the South Coast (29.3%) and the San Francisco Bay Area (30.6%).[12] These coastal urban regions are the areas where rents have been rising most rapidly, and while single-family homes represent a relatively smaller share of occupied rentals in these high-cost regions, they still house a significant number of renters in these areas.

Other renters live in apartments that were built within the last few decades. This means these units are not allowed to be covered by rent control under Costa-Hawkins, but could become covered if Prop. 10 passes and cities choose to adopt new rent control policies that include more recently built rentals. In the four largest cities that have current rent control policies in place — Los Angeles, San Francisco, San Jose, and Oakland — Costa-Hawkins limits rent controls to properties built before about 1980 (see Table 1). Across these four cities combined, 14.7% of renter-occupied apartments (198,000 homes) were built between 1980 and 1999, and another 8.5% (115,000 units) were built between 2000 and 2016 according to a Budget Center analysis of US Census data from 2016. If these cities chose to extend rent control to apartments built before 2000, for example, instead of before the year currently allowed by Costa-Hawkins, nearly 200,000 additional apartments could be covered by their rent stabilization policies.

How Could Low- and Moderate-Income Californians Be Helped by Proposition 10?

California’s housing affordability crisis most deeply affects low- and moderate-income households and renters.[13] Allowing local jurisdictions to expand rent control could provide more of California’s current renters with a guarantee of modest, predictable rent increases as long as they remain in the same home, protecting them from large or repeated jumps in rent that may outpace any increase in their incomes. This protection from rapidly rising rents is particularly valuable for lower-income households because wages and earnings for low- and midwage workers have experienced only sluggish growth in recent years, even as the economy overall has been improving.[14] Savings on rent due to rent control vary greatly depending on how local rent control ordinances are structured and how long a tenant has been in the same home, but they can be very large for long-term tenants in jurisdictions with strong control of rents. A study that examined renters in San Francisco from 1995 to 2012, for example, found that renters saved an average of $2,300 to $6,600 per person each year if they lived in a rent-controlled apartment.[15]

Rent control also encourages tenants to remain in the same home longer, both because tenants are less likely to be forced out by unaffordable rent increases and because they are less likely to be able to find equally low rent if they move to a new home. Increased housing stability is generally associated with positive health, social, and educational outcomes, particularly for children.[16] In some cases, rent control can discourage renters from moving to access new jobs or other opportunities or to secure a housing unit that better meets their needs — a less positive outcome — but this reduced mobility may be better understood as renters requiring a higher payoff from moving to compensate for the higher housing costs that would result from moving. At a neighborhood level, fewer moves among tenants translates into greater neighborhood stability, which can also mean a slower rate of gentrification in neighborhoods subject to gentrification pressures.[17] [18]

Are There Potential Disadvantages for Low- and Moderate-Income Californians of Allowing an Expansion of Rent Control?

Local rent control policies can create incentives for landlords that have the undesired effect of working against the interests of low- and moderate-income renters. However, these potential negative effects can often be minimized with careful design of local rent controls and by coupling rent control with other local policies:

- Capping allowed rent increases can incentivize landlords to neglect maintenance of their rental properties, but local rent control policies can address this issue by allowing landlords to pass through to renters some maintenance and improvement costs. Active local code enforcement can also help ensure that rent-controlled properties continue to meet health and safety standards.

- Rent controls that apply to newly built housing, as Prop. 10 would allow cities to pursue, tend to reduce the expected profits from building market-rate rental housing, particularly in areas with rapidly rising rents, and could therefore discourage developers from building as much new rental housing as they otherwise would have. However, local rent control policies can address this problem by choosing to exclude newly constructed rental units from rent control for a period of years long enough to maintain an adequate incentive for developers. For example, newly built market-rate rental units could be exempted from rent control for 15 or 20 years after construction, allowing developers a set period of time in which to recoup their investment costs and collect potentially higher profits before the unit falls under rent control.

- Extending rent control to new types of rental housing like single-family homes or more recently built apartments, as cities could choose to do if Prop. 10 passes, would tend to reduce the expected profits from renting out these homes, especially in areas with rapidly increasing rents. In turn, this would create an incentive for landlords with these types of properties to remove them from the rental market, converting them to ownership housing and selling them in order to cash out on the profits generated by a strong housing market. In fact, research shows that owners of rental properties subject to rent control are more likely to convert their properties to ownership housing.[19] Removing units from the rental market harms tenants in two ways: tenants residing in those units may be forced to move, and the reduction in the overall supply of rental housing will tend to intensify competition for vacant units and drive up rents in homes that are not subject to rent control. However, local jurisdictions can strive to minimize this outcome by coupling rent control with other tenant-protection policies. They can allow only “just cause” evictions and require significant compensation for tenants evicted when landlords seek to remove units from the rental market. They can also guarantee affordable legal services for tenants facing eviction to be sure these tenant protections are enforced. They can also restrict the conditions under which apartments can be converted to ownership condominiums, and implement separate policies designed to incentivize more housing development.

Of these potential negative effects of allowing an expansion of rent control, the removal of homes from the rental market may be the most likely to harm low- and moderate-income Californians. This is because a reduction in the overall number of rental units exacerbates the shortage of rental housing, which is a key driver of the rapid increase in market-rate rents, and also because local rent control and tenant-protection policies cannot fully prevent properties from being removed from the rental market. These negative effects would, however, be felt only by a subset of low-income renters: those who are seeking a new rental home or living in units not covered by rent control. They would therefore particularly affect individuals and families entering the local rental market for the first time (e.g., young adults moving out of their parents’ homes, or individuals moving to access job or educational opportunities, including those moving into California from out of state) and renters who are involuntarily forced to move to a new home (e.g., tenants whose homes are converted to ownership housing, or families in financial crisis who are evicted for nonpayment of rent). On the other hand, as noted above, expanding rent control would produce substantial benefits for continuing renters in homes newly subject to rent control who do not need or want to move. These substantial benefits for continuing renters must be weighed against the potential negative impacts for new renters and movers.

An expansion of local rent control policies would also likely reduce state and local government revenues, according to the Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO), largely because the value of affected rental properties would be expected to drop, leading to lower property tax revenues over time.[20] Low- and moderate-income Californians benefit from the public services and supports funded by local and state revenues, so would be affected by a decline in these revenues. How much revenues decline would depend directly on how many local communities chose to extend rent control to newly allowed types of rental housing and how their rent control policies were designed. The drop in public revenues could range from insignificant to hundreds of millions of dollars annually, according to the LAO. This loss of revenues to support public services should be considered together with the substantial benefits to continuing renters from paying lower and more stable rents over time.

Conclusion: Understanding How Proposition 10 Relates to Other Policies to Address Housing Affordability

An expansion of local rent control policies, as Prop. 10 would allow, would not increase the supply of rental housing, and the shortage of rental housing is a root cause of California’s rapidly rising rents. If anything, as noted above, an expansion of rent control would be likely to encourage some landlords to remove current rental properties from the rental market, contributing to a decrease in the rental housing supply. For that reason, rent control expansion alone would not solve California’s housing affordability crisis. Other policies that are designed to increase the state’s supply of rental housing would also be needed, such as direct state and local investment in building affordable rental housing, financial or regulatory incentives to promote more private development of rental housing (such as inclusionary zoning or density bonuses), and local government accountability to support housing development at levels that meet the demand for rental housing. An expansion of rent control also would not address the needs of all renters, since rent control primarily benefits current renters who do not need or want to move to new homes, and may even disadvantage new renters and those who must or want to move.

However, many California renters are struggling to afford their housing costs now, and rent control is one of the few financially feasible and scalable policy tools available to address the immediate needs of those facing rents in the private market that are rising faster than incomes. Given the scale of the housing affordability crisis in California, policies that address affordability within housing provided by the private market are necessary, since the vast majority of renters will have to live in market-based housing. An expansion of rent control has advantages as a policy option to address private-market rents because it requires limited direct state and local costs and can be implemented and address housing affordability immediately. Local jurisdictions can also design local rent control policies in ways that minimize the potential negative effects of rent control and/or couple them with other policies that protect tenants and incentivize housing development.

Indeed, the design of local policies is central to the expected effects of Prop. 10 on housing affordability in California. If Prop. 10 passes, its effects would directly depend on how cities and other local jurisdictions chose to use their expanded authority to limit rent increases in rental housing at the local level. As a result, passage of Prop. 10 would primarily set the stage for local policymakers and voters to decide whether and how broadly to implement rent control policies within their local jurisdictions.

Endnotes

[1] Legislative Analyst’s Office, “Proposition 10: Expands Local Governments’ Authority to Enact Rent Control on Residential Property. Initiative Statute. Analysis by the Legislative Analyst,” in Secretary of State’s Office, California General Election Tuesday November 6, 2018: Official Voter Information Guide, pp. 58-59.

[2] Sara Kimberlin, Rents and Home Prices Are High in Many Parts of California (California Budget & Policy Center: September 2017).

[3] Sara Kimberlin, Californians in All Parts of the State Pay More Than They Can Afford for Housing (California Budget & Policy Center: September 2017).

[4] Sara Kimberlin, Californians in All Parts of the State Pay More Than They Can Afford for Housing (California Budget & Policy Center: September 2017).

[5] Sara Kimberlin, Making Ends Meet (California Budget & Policy Center: December 2017).

[6] Peter Dreier, Rent Deregulation in California and Massachusetts: Politics, Policy, and Impacts – Part II (International and Public Affairs Center, Occidental College, May 1997).

[7] Legislative Analyst’s Office, “Proposition 10: Expands Local Governments’ Authority to Enact Rent Control on Residential Property. Initiative Statute. Analysis by the Legislative Analyst,” in Secretary of State’s Office, California General Election Tuesday November 6, 2018: Official Voter Information Guide, pp. 58-59.

[8] The cities of Mountain View and Richmond passed rent stabilization measures in November 2016.

[9] The exception would be in cities with rent control policies still on the books from before the passage of Costa-Hawkins that apply to rental housing that is currently exempt from rent control under Costa-Hawkins. For example, the City of Berkeley’s pre-Costa-Hawkins rent control policy included vacancy control, and that portion of the ordinance was never repealed, so it would go back into effect immediately if Prop. 10 passes.

[10] Birkenfeld v. City of Berkeley, California Supreme Court, 17 Cal.3d 129 (1976).

[11] Unless otherwise noted, statistics in this section are from a Budget Center analysis of US Census Bureau, American Community Survey public-use microdata for California from 2015-2016, downloaded from IPUMS-USA (University of Minnesota, www.ipums.org).

[12] In terms of the remaining regions of California, renter households occupying single-family homes represented 48.7% of renters in the Inland Empire, 44.2% in the Sacramento Region, and 43.9% in the Central Coast in 2015-2016.

[13] Sara Kimberlin, Californians in All Parts of the State Pay More Than They Can Afford for Housing (California Budget & Policy Center: September 2017).

[14] Amy Rose, Policy Choices Can Help More Midwage Workers Share in Economic Gains (California Budget & Policy Center, September 2017).

[15] Rebecca Diamond, Timothy McQuade, and Franklin Qian, The Effects of Rent Control Expansion on Tenants, Landlords, and Inequality: Evidence from San Francisco (National Bureau of Economic Research, January 2018).

[16] Nicole Montojo, Stephen Barton, and Eli Moore, Opening the Door for Rent Control: Toward a Comprehensive Approach to Protecting California’s Renters (Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, University of California, Berkeley, September 2018), p.15.

[17] Nicole Montojo, Stephen Barton, and Eli Moore, Opening the Door for Rent Control: Toward a Comprehensive Approach to Protecting California’s Renters (Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, University of California, Berkeley, September 2018).

[18] Manuel Pastor, Vanessa Carter, and Maya Abood, Rent Matters: What Are the Impacts of Rent Stabilization Mesaures? (Program for Environmental and Regional Equity, University of Southern California, forthcoming).

[19] Rebecca Diamond, Timothy McQuade, and Franklin Qian, The Effects of Rent Control Expansion on Tenants, Landlords, and Inequality: Evidence from San Francisco (National Bureau of Economic Research, January 2018); Legislative Analyst’s Office, Review of Proposed Statutory Initiative Pertaining to Rent Control (A.G. File No. 17-0041), December 12, 2017.

[20] Legislative Analyst’s Office, “Proposition 10: Expands Local Governments’ Authority to Enact Rent Control on Residential Property. Initiative Statute. Analysis by the Legislative Analyst,” in Secretary of State’s Office, California General Election Tuesday November 6, 2018: Official Voter Information Guide, pp. 58-59.