For the Center for Nonprofit Management’s “2018 Economic Forecast,” Executive Director Chris Hoene presented on Governor Brown’s proposed 2018-19 state budget and potential state budget policy changes affecting the nonprofit sector.

January 2018 | By Chris Hoene

Download Full PresentationFor the Center for Nonprofit Management’s “2018 Economic Forecast,” Executive Director Chris Hoene presented on Governor Brown’s proposed 2018-19 state budget and potential state budget policy changes affecting the nonprofit sector.

Join our email list!

On January 10, Governor Jerry Brown released a proposed 2018-19 budget that prioritizes building up reserves amid deep uncertainty about looming federal budget proposals, the impacts of the recently enacted federal tax bill, and future economic conditions. The Governor forecasts revenues that are $4.2 billion higher (over a three-year “budget window” from 2016-17 to 2018-19) than previously projected in the 2017-18 budget enacted last June, driven largely by continued economic growth. The Governor’s budget assumes no changes to current federal policies and funding levels and is not yet able to account for the potential impacts of the Republican tax bill passed in late December.

The Governor’s proposed budget reflects some notable advances, such as providing funding to fully implement the Local Control Funding Formula for K-12 education (designed to direct additional resources to disadvantaged students), continuing to invest in early education and higher education, and creating a home visiting pilot program that would offer a range of supports for families participating in welfare-to-work (CalWORKs). In addition, the proposal maintains resources to address the impact of federal actions targeting the state’s immigrant residents. Yet, the Governor also places a heavy emphasis on building California’s reserves. He proposes making a one-time supplemental deposit of $3.5 billion to the state’s rainy day fund, in addition to the $1.5 billion required by Proposition 2 (2014). This proposed $5.0 billion deposit would raise the rainy day fund balance to the Prop. 2 maximum of 10 percent of General Fund tax revenues.

While the prospect of major changes in federal policy is a reason for caution, this budget could strike a better balance between putting away funds for a rainy day and boosting investments now that would help more Californians make ends meet and advance economically. Opportunities include increasing basic income support provided by the California Earned Income Tax Credit (CalEITC), boosting cash assistance for low-income seniors and people with disabilities (SSI/SSP), raising CalWORKs grant levels, and advancing new proposals to address our state’s affordable housing crisis.

The 2018-19 state budget debate will move forward amid many unknowns at the federal level, making it critical that California’s congressional delegation and state lawmakers seek to advance smart policy choices that broaden economic opportunity and push back against federal proposals that would harm people and communities across the state.

The following sections summarize key provisions of the Governor’s proposed 2018-19 budget.

Download full report (PDF) or use the links below to browse individual sections of this report:

Within the past year, both the US and California have seen their lowest unemployment rates since 2000. The Administration expects the state’s unemployment rate to remain low over the next few years, at around 5 percent. The Governor’s proposed budget assumes that California’s economy will grow modestly over the next five years, but with jobs added at a slower pace than during the past five years. This expected slowdown is due in part to the state’s high housing costs, which limit the ability of employers to recruit workers to move into or within the state to access jobs. As inflation has begun to rise nationally, California’s high housing costs are also expected to contribute to continuing higher inflation within the state compared to the US.

While projecting modest economic growth, the Administration points to the risk of a national recession, noting that this current period of growth has lasted more than eight years and that unemployment rates nationally and in California are at “levels only seen near the end of an expansion.” While this risk is worth keeping in mind, a recession in the next few years is not inevitable. The Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO) and other experts have pointed out that the recent long period of expansion does not in and of itself mean that another recession is likely soon. Other potential economic risks noted by the Administration include a stock market correction and geopolitical events that disrupt global trade. It is important to note that the Governor’s budget does not incorporate projected economic impacts from the recently passed federal tax bill, with assessment of those effects postponed to the May Revision.

The Governor’s proposed budget projects higher-than-expected revenues due to an improved economic forecast. However, the Administration cautions that its revised revenue projections are subject to uncertainty. Most notably, the estimates do not take into account the impact of the recently enacted federal tax legislation, which will have significant implications for California. Budget documents note that the Administration’s revised forecast in May will include preliminary estimates of the impact of the new tax law.

The proposed budget projects that total General Fund revenues (before transfers) over the three-year “budget window,” from 2016-17 to 2018-19, will be about $4.2 billion higher than the projections included in the 2017-18 budget agreement. The stronger revenue forecast is largely driven by higher personal income tax (PIT) and sales and use tax (SUT) revenue projections. Specifically, the Governor expects PIT revenues during this three-year period to be nearly $2.9 billion higher, SUT revenues to be $1.5 billion higher, and corporation tax (CT) revenues to be $358 million lower than expected when the budget for the current fiscal year was signed into law. Higher PIT projections largely reflect stronger wage gains, particularly among higher-income taxpayers, while higher SUT projections are due to stronger-than-expected consumer spending and capital equipment spending by businesses. Lower CT revenues result from weaker-than-anticipated corporate tax receipts in spite of strong corporate profits.

California voters approved Proposition 2 in November 2014, amending the California Constitution to revise the rules for the state’s Budget Stabilization Account (BSA), commonly referred to as the rainy day fund. Prop. 2 requires an annual set-aside equal to 1.5 percent of estimated General Fund revenues. An additional set-aside is required when capital gains revenues in a given year exceed 8 percent of General Fund tax revenues. For 15 years — from 2015-16 to 2029-30 — half of these funds will be deposited into the rainy day fund, and the other half will be used to reduce certain state liabilities (also known as “budgetary debt”).

Based on the Governor’s revenue projections for 2018-19, Prop. 2 would constitutionally require the state to deposit $1.5 billion into the BSA (and to use an additional $1.5 billion to repay budgetary debt). In addition, the Governor proposes to make an optional, one-time supplemental transfer of $3.5 billion from the General Fund to the BSA. (The total transfer to the BSA would be $5.0 billion: $1.5 billion as required by the state Constitution, plus the $3.5 billion supplemental transfer.) As a result, the BSA would total $13.5 billion by the end of the 2018-19 fiscal year.

Under the scenario outlined by the Governor, the BSA would reach its constitutional maximum of 10 percent of General Fund tax revenues in 2018-19. When this limit is reached, Prop. 2 requires that any additional dollars that would otherwise go into the BSA be spent on infrastructure, including spending on deferred maintenance. In other words, Prop. 2 prohibits these additional dollars from being allocated to ongoing programs and services.

The BSA is not California’s only reserve fund. Each year, the state deposits additional funds into a “Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties” (SFEU). The Governor’s proposed budget calls for an SFEU balance of $2.3 billion. Including this fund, the Governor’s proposal would build state reserves to a total of $15.8 billion in 2018-19.

One additional implication of the Governor’s proposal is that the $3.5 billion supplemental transfer to the BSA may not be readily available to help the state meet needs created by future developments, such as federal budget cuts. In order to access the BSA funds, the Governor would need to declare a “budget emergency,” defined by Prop. 2 as a disaster or extreme peril, or insufficient resources to maintain General Fund expenditures at the highest level of spending in the three most recent fiscal years, adjusted for state population growth and the change in the cost of living. In contrast, an additional transfer to the SFEU would leave the funds more readily available to help the state address uncertainties. This is because funds in the SFEU can be accessed without the need to declare a budget emergency.

The California Earned Income Tax Credit (CalEITC) is a refundable state tax credit designed to boost the incomes of low-earning workers and their families and help them afford basic expenses. The credit was established by the 2015-16 budget agreement and was subsequently expanded as part of the 2017-18 budget deal.

Prior to this expansion, the CalEITC provided an average credit of more than $500 to around 370,000 families and individuals across the state. (Those with dependents received an average of more than $800, while those without dependents received an average of just over $100.) Many more Californians will likely benefit from the CalEITC this year due to the credit expansion.

The Governor’s proposed budget makes no changes to the CalEITC. Consistent with prior years, the Governor proposes maintaining the CalEITC “adjustment factor” at 85 percent for tax year 2018. (California policymakers must specify the CalEITC adjustment factor in each year’s state budget. This factor sets the state EITC at a percentage of the federal EITC, thereby determining the size of the state credit available in the following year.) Additionally, the Administration projects that the CalEITC will reduce state General Fund revenues by $343 million in 2017-18 and by $353 million in 2018-19.

The proposed budget also does not appear to include any funding to maintain community-based efforts to promote the CalEITC in order to boost credit claims. The 2016-17 and 2017-18 budget agreements each included $2 million for grants to community-based organizations and other local entities to support efforts to raise awareness of the CalEITC. Education and outreach efforts are important because evidence suggests that many families who were eligible for the credit missed out on it in recent years.

Approved by voters in 1988, Proposition 98 constitutionally guarantees a minimum level of funding for K-12 schools, community colleges, and the state preschool program. The Governor’s proposed budget assumes a 2018-19 Prop. 98 funding level of $78.3 billion for K-14 education, $3.1 billion above the revised 2017-18 minimum funding level. The Prop. 98 guarantee tends to reflect changes in state General Fund revenues and growth in the economy, and estimates of 2017-18 General Fund revenue in the proposed budget are higher than those in the 2017-18 budget agreement. As a result, the Governor’s proposed 2018-19 budget reflects a $75.2 billion Prop. 98 funding level for 2017-18, $688 million more than the level assumed in the 2017-18 budget agreement.

California’s school districts, charter schools, and county offices of education (COEs) provide instruction to approximately 6.2 million students in grades kindergarten through 12. The Governor’s proposed budget increases funding for the state’s K-12 education funding formula — the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF) — providing sufficient dollars to reach the LCFF’s target funding level in 2018-19. The proposed budget also pays off outstanding state obligations to school districts. Specifically, the Governor’s proposed budget:

A portion of Proposition 98 funding supports California’s community colleges (CCCs), which help prepare approximately 2.4 million full-time students to transfer to four-year institutions as well as obtain training and skills for immediate employment. The Governor’s budget proposes a new funding formula for CCC general-purpose apportionments and also calls for establishing a fully online community college. Specifically, the proposed budget:

The Governor’s proposed budget also provides CCCs with $264.3 million in one-time funding for deferred maintenance and an additional $32.9 million to fund a new Student Success Completion Grant, consolidating funding for the Full-Time Student Success Grant and the Community College Completion Grant and basing the new grant on the number of units a qualifying student takes each semester or each year.

California supports two public four-year higher education institutions: the California State University (CSU) and the University of California (UC). The CSU provides undergraduate and graduate education to roughly 479,000 students on 23 campuses, and the UC provides undergraduate, graduate, and professional education to about 273,000 students on 10 campuses.

The Governor’s proposed 2018-19 budget includes modest increases in General Fund spending for the CSU and the UC, with the expectation that these institutions will implement certain improvements. Specifically, the proposed spending plan:

California’s child care and development system allows parents with low and moderate incomes to find jobs and remain employed while caring for and preparing children for school. State policymakers dramatically cut funding for these programs during and after the Great Recession, which hampered families’ access to safe and reliable early care and education. Even as the state’s economy continues to grow and revenues increase faster than earlier forecasted, funding for the child care and development system in the current 2017-18 fiscal year remains more than $500 million below the pre-recession level, after adjusting for inflation.

The 2018-19 budget proposal creates a new competitive grant program with one-time funding of $167.2 million ($125 million Proposition 98, $42.2 million federal TANF funds). The stated goal of the Inclusive Early Education Expansion Program is to “increase the availability of inclusive early education and care for children aged 0 to 5 years old” in order to boost school readiness and improve academic outcomes for children from low-income families and children with exceptional needs. The grants are to be targeted to areas with low incomes and low access to care. In addition, the budget proposal:

Last year, congressional leaders made multiple attempts to repeal the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and substantially reduce federal funding for Medicaid, which provides health coverage to tens of millions of Americans with low incomes, including more than 13 million in California. (Medi-Cal is California’s Medicaid program.) While these efforts failed, the federal government has pursued other changes that threaten to destabilize insurance markets and reduce the number of people with health coverage. For example, the Republican-backed tax bill – which President Trump signed into law last month – repealed the financial penalty (effective in 2019) for people who fail to opt in for health coverage. This change is expected to both reduce the number of people with health insurance and drive up premiums for those who continue to purchase coverage on the individual market. In addition, President Trump has used his executive authority to advance a number of policies designed to weaken the ACA.

The Governor’s budget summary acknowledges the uncertainty surrounding these potential federal policy changes, including whether they would “ultimately be approved or when they would take effect.” As a result, the Governor’s proposals assumes that current federal and state health policies will remain in place.

In addition, the Governor’s proposed budget:

CHIP is a joint federal-state program that supports health insurance for almost 9 million children throughout the US during the course of a year, including over 2 million in California. In California, CHIP-eligible children from families with incomes up to 266 percent of the federal poverty line (FPL) —$65,436 for a family of four — receive health care services through Medi-Cal. (These children previously would have been enrolled in the Healthy Families Program, which was eliminated in 2013). Through separate, smaller programs, CHIP also supports health care services for certain children whose families earn up to 322 percent of the FPL in San Francisco, San Mateo, and Santa Clara counties, as well as for pregnant women in families with incomes up to the same level.

Since late 2015, the federal government has paid 88 percent of CHIP costs in California, with the state covering the remaining 12 percent. Previously, the federal share was set at 65 percent. Last year, with the program authorized only through September 2017, the Governor assumed that Congress would reauthorize CHIP at the 65 percent level effective October 1, 2017. However, Congress failed to allocate long-term federal funding for CHIP and has only managed to approve temporary funding that expires in March 2018. The short-term extension funded CHIP at 88 percent, and the Governor expects about $150 million General Fund savings to be reflected in the May Revision. These savings are not reflected in the January proposal because the funding extension occurred after the budget was finalized.

The Governor’s proposed 2018-19 budget still assumes that Congress will eventually renew CHIP funding, at the lower 65 percent level. If Congress does not reauthorize CHIP, however, the Affordable Care Act requires California to continue coverage for those children receiving care through Medi-Cal, with a 50 percent federal share. On a conference call with stakeholders, Administration officials did not confirm that the state would continue to cover the 32,000 children and pregnant women who do not qualify for federally funded Medi-Cal.

The California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) program provides modest cash assistance for 860,000 low-income children while helping parents overcome barriers to employment and find jobs. CalWORKs is the state’s version of the federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program. Counties receive most of their funding to support CalWORKs activities (including employment services and certain child care services) through the “CalWORKs single allocation,” which has historically been budgeted based on projected caseload.

Last year, in response to the continued decline in the CalWORKs caseload, the 2017-18 budget agreement reduced the single allocation by about $140 million and required the Administration and the counties to devise a new budgeting methodology to “address the cyclical nature of the caseload changes and impacts to county services.” The Governor’s 2018-19 proposed budget includes a one-time increase in the single allocation of $187 million until the revised methodology is adopted; this is an 11 percent increase relative to the 2017-18 allocation of $1.7 billion. Additionally, with the state minimum wage scheduled to increase from $11 to $12 on January 1, 2019 for large businesses, CalWORKs spending is expected to decrease by $1.2 million General Fund as more families earn an income that is above the eligibility limit (but still far below the level needed to make ends meet).

At their current levels, CalWORKs grants fail to lift most families out of “deep poverty,” which is defined as having an income that is below half of the federal poverty line ($10,210 for a family of three in 2017). The Governor does not propose any increase to CalWORKs grant levels or time limits, even though this would be necessary to fully restore cuts that state policymakers made to the program during and after the Great Recession.

The Governor’s proposal does allocate a total of $158.5 million in one-time TANF funds through 2021 for a new voluntary home visiting pilot program, with $26.7 million in the first year. Evidence-based home visiting programs offer resources and parenting skills development to new and expecting parents, particularly those who are at-risk. The proposed initiative would apply existing models currently in place in the state to serve first-time CalWORKs parents with the aim of encouraging healthy development of low-income children, promoting healthy parenting, and preparing parents for work. On a conference call with stakeholders, Administration officials indicated an implementation target date of January 2019 for the pilot program.

Supplemental Security Income/State Supplementary Payment (SSI/SSP) grants help well over 1 million low-income seniors and people with disabilities to pay for housing, food, and other basic necessities. Grants are funded with both federal (SSI) and state (SSP) dollars. State policymakers made deep cuts to the SSP portion of these grants in order to help close budget shortfalls that emerged following the onset of the Great Recession in 2007. The SSP portions for couples and for individuals were reduced to federal minimums in 2009 and 2011, respectively. Moreover, the annual statutory state cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) for SSI/SSP grants was eliminated beginning in 2010-11, after having been suspended for several years.

California took a modest step toward reinvesting in SSI/SSP by funding a 2.76 percent COLA for the SSP portion of the grant in the 2016-17 fiscal year. This boosted the monthly SSP grant to $160.72 for individuals (an increase of $4.32) and to $407.14 for couples (an increase of $10.94). However, SSP grants were not further increased in 2017-18, and these grants would continue to remain frozen at the current levels under the Governor’s proposed 2018-19 budget.

The Administration does project that the federal government will increase the SSI portion of the grant by 2.6 percent effective January 1, 2019. As a result of this projected federal increase:

Currently, about 130,000 people who have been convicted of a felony offense are serving their sentences at the state level — down from a peak of around 173,600 in 2007. Most of the individuals who are currently incarcerated — nearly 114,300 — are housed in state prisons designed to hold slightly more than 85,000 people. This level of overcrowding is equal to 134.3 percent of the prison system’s “design capacity,” which is below the prison population cap — 137.5 percent of design capacity — established by a 2009 federal court order. (In other words, the state is in compliance with the court order.) In addition, California houses nearly 15,700 individuals in facilities that are not subject to the court-ordered cap, including fire camps, in-state “contract beds,” out-of-state prisons, and community-based facilities that provide rehabilitative services.

The sizeable drop in incarceration has resulted largely from a series of policy changes adopted by state policymakers and the voters in the wake of the federal court order. The most recent reform was Proposition 57, a 2016 ballot measure that provided state officials with new tools to address ongoing overcrowding in state prisons. Prop. 57:

With the implementation of Prop. 57, the average daily number of incarcerated adults is projected to drop from just over 130,300 in 2017-18 to about 127,400 in 2018-19 (a 2.2 percent decline), according to Administration estimates. Moreover, the Administration anticipates that by freeing up space in state prisons, Prop. 57 — along with other recent criminal justice reforms — will allow the state to end the use of one of two remaining out-of-state prison facilities by the end of the current fiscal year (June 30), and to end the use of the other facility by the fall of 2019. Currently, more than 4,200 Californians are housed in facilities in Arizona and Mississippi because there is no room for them in state prisons given the court-imposed prison population cap.

In addition, the Governor’s proposed 2018-19 budget includes:

Finally, the Administration estimates that Prop. 47 will generate net state savings of $64.4 million in 2017-18, with ongoing annual savings expected to be approximately $69 million. Approved by California voters in 2014, Prop. 47 reduced penalties for certain nonviolent drug and property crimes from felonies to misdemeanors and generally allowed people who were serving a felony sentence for these crimes at the time of Prop. 47’s passage to petition the court to have their sentence reduced to a misdemeanor term. The annual state savings from Prop. 47 are required to be allocated as follows: 65 percent to mental health and drug treatment programs, 25 percent to K-12 public school programs for at-risk youth, and 10 percent to trauma recovery services for crime victims.

The Administration notes that more than half of all children born in California have at least one foreign-born parent and that immigrants have been critical to California’s labor force and economic growth throughout the state’s history. Given the prominence of immigrants in California’s population and the state’s economy, recent and ongoing federal actions to limit immigration and aggressively enforce immigration laws particularly impact California. These issues have been an area of particular tension between the Trump Administration and California’s state and local governments.

The Governor’s proposed budget continues an expansion of state resources included in last year’s budget to address federal actions that affect California’s immigrant residents. The proposed 2018-19 budget includes $45 million General Fund dedicated to legal services for people seeking help with securing legal immigration status, defense against deportation, and other immigration services, as well as $3 million to assist undocumented immigrants who are unaccompanied minors, both through the Department of Social Services. The Governor’s budget also maintains increased funding for the Attorney General’s office to address federal actions and proposes to make this increased funding permanent.

Last year, the Governor and Legislature passed the Road Repair and Accountability Act of 2017 (Senate Bill 1), a 10-year, $55 billion transportation package. SB 1 funds improvements in state and local transportation infrastructure by increasing the state gas tax for the first time since 1994 (raising it to its inflation-adjusted level relative to 1994) and through a series of other fuel taxes, vehicle fees, and other transportation-related fees. The Governor’s proposed 2018-19 budget includes $4.6 billion in funding provided by SB 1, split evenly between state and local transportation projects.

The Governor’s proposed budget includes several references to California’s high housing costs and their implications for families and individuals as well as the economy. The Governor notes the large percentage of Californians paying more than half of their incomes toward housing, the negative impact of high housing costs on job growth and inflation, and the significant gap between housing production and demand. To begin to address California’s housing affordability crisis, last year the Legislature passed, and the Governor signed, a comprehensive package of housing legislation. These bills included multiple strategies to improve housing affordability, including directly financing affordable housing production, facilitating private-market housing production, and increasing local accountability for accommodating a fair share of new housing development.

The housing proposals in the Governor’s budget reflect implementation of components of the legislative housing package. Specifically, the Governor’s proposed budget:

These proposals, combined with continuation of existing programs, loans, and tax credits administered through various state departments and agencies, bring the total proposed state funding for affordable housing and homelessness to $4.37 billion.

California Competes provides income tax credits to certain businesses in order to encourage companies to move to, stay in, or expand in California. The program was established in 2013, together with two other economic development programs, as a replacement for the state’s Enterprise Zone programs. Under current law, California Competes will expire in 2017-18.

The Administration proposes extending California Competes for five years and making $180 million in credits available to qualifying businesses in each of those years. The proposed budget also provides $20 million annually to assist small businesses and “reconstitutes” $50 million per year to encourage businesses to hire people facing barriers to work, such as parolees, CalWORKs parents, and veterans.

A recent Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO) report recommended that the Legislature end California Competes based on a preliminary evaluation of the program. Specifically, the LAO found that while the “executive branch has made a good faith effort to implement California Competes,” the program produced “windfall benefits” to businesses in some cases without any increase in overall state economic activity. Additionally, the LAO noted that it is difficult to assess the effectiveness of targeted tax incentives and suggested that “broad-based tax relief” for all businesses would be preferable.

Join our email list!

For the Budget Center’s annual budget preview, “The State Budget Process and Key Issues to Watch for in 2018,” Director of Research Scott Graves provided an overview of the state budget process and highlighted opportunities for public engagement.

Join our email list!

Director of Research Scott Graves provided an overview of the California budget process for the California Environmental Justice Alliance’s legislative call. Scott discussed how to actively engage in the budget process effectively, identified key players, and highlighted the differences between the legislative and budget pathways.

Join our email list!

This post is the first in a California Budget & Policy Center series that will discuss the tax cuts proposed by President Trump and Republican congressional leaders and explore the implications for Californians and the nation.

Now that Republican leaders in Washington, DC, have moved on from their latest failed effort to repeal the Affordable Care Act, they have quickly turned their attention to a combination of tax cuts and deep spending reductions that together would have dire implications for many low- and middle-income people in California and across the nation. In September, the Trump Administration and leaders in the US House of Representatives and Senate unveiled their unified tax framework, which would provide significant tax cuts that predominantly benefit the wealthy.

Republican leaders are developing the full details of their tax plan in parallel with efforts to enact a budget for fiscal year 2018, and in order to offset the costs of tax cuts they are also seeking draconian cuts in spending on an array of critical programs and services. Congressional rules allow for a “fast track” process to pass tax cuts and certain spending reductions with a simple majority in the Senate (without needing any Democratic votes) — a process known as “reconciliation.” If GOP leaders pursue their proposed tax cuts, they will enact a massive redistribution of wealth that would be, in part, paid for through budget cuts to programs that help low- and middle-income families make ends meet and access greater economic opportunity.

Despite their stated goal of providing a tax cut for middle-class families, the latest GOP framework would provide the vast majority of its benefits to wealthier Americans and corporations. For instance, the current tax framework is most specific about repealing the estate tax; ending the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT); cutting corporate tax rates; potentially lowering the highest income tax rates; and preserving tax preferences for mortgage interest — in short, a range of benefits that accrue disproportionately to wealthier households.

In contrast, the tax proposal’s benefits for working families are less explicit — and apparently far less substantial. Based on information released so far, the clearest proposals benefiting middle-class households are a doubling of the standard deduction and an unspecified increase in the Child Tax Credit, though the tax framework also includes some vague language about future “additional measures.” However, accounting for changes like the elimination of personal exemptions and an increase in the bottom marginal income tax rate for some filers, many low- and middle-income families could see little benefit, if any.

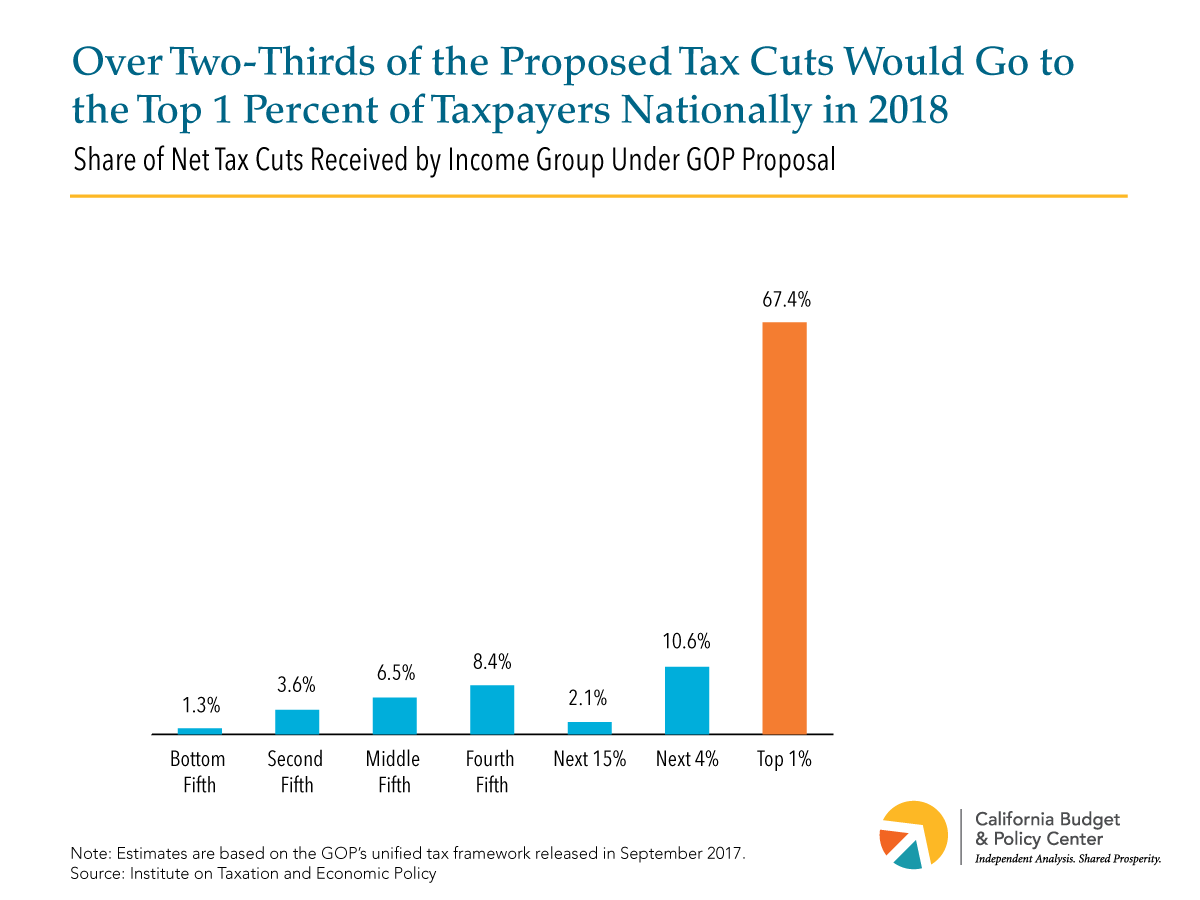

Though the President had promised that the rich “will not be gaining at all with this plan,” the numbers tell a different story. In fact, a recent analysis of the GOP tax package points to a vastly unfair distribution of its benefits. According to the nonpartisan Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, the top 1 percent of households — a group whose annual incomes are at least $615,800 and average over $2 million — would receive over two-thirds of the tax cuts in 2018 (see chart below), an amount equivalent to 4.3 percent of this group’s pre-tax income. The bottom 60 percent of Americans, however, would receive 11.4 percent of the tax cuts, equal to a meager 0.7 percent of this group’s total income. What’s more, these Americans would be most likely to be affected by corresponding federal spending cuts that GOP leaders are proposing to offset the overall cost of the tax cuts.

In other words, the latest GOP tax plan is heavily skewed to benefiting the wealthiest households in the US, likely at the expense of many low- and middle-income households.

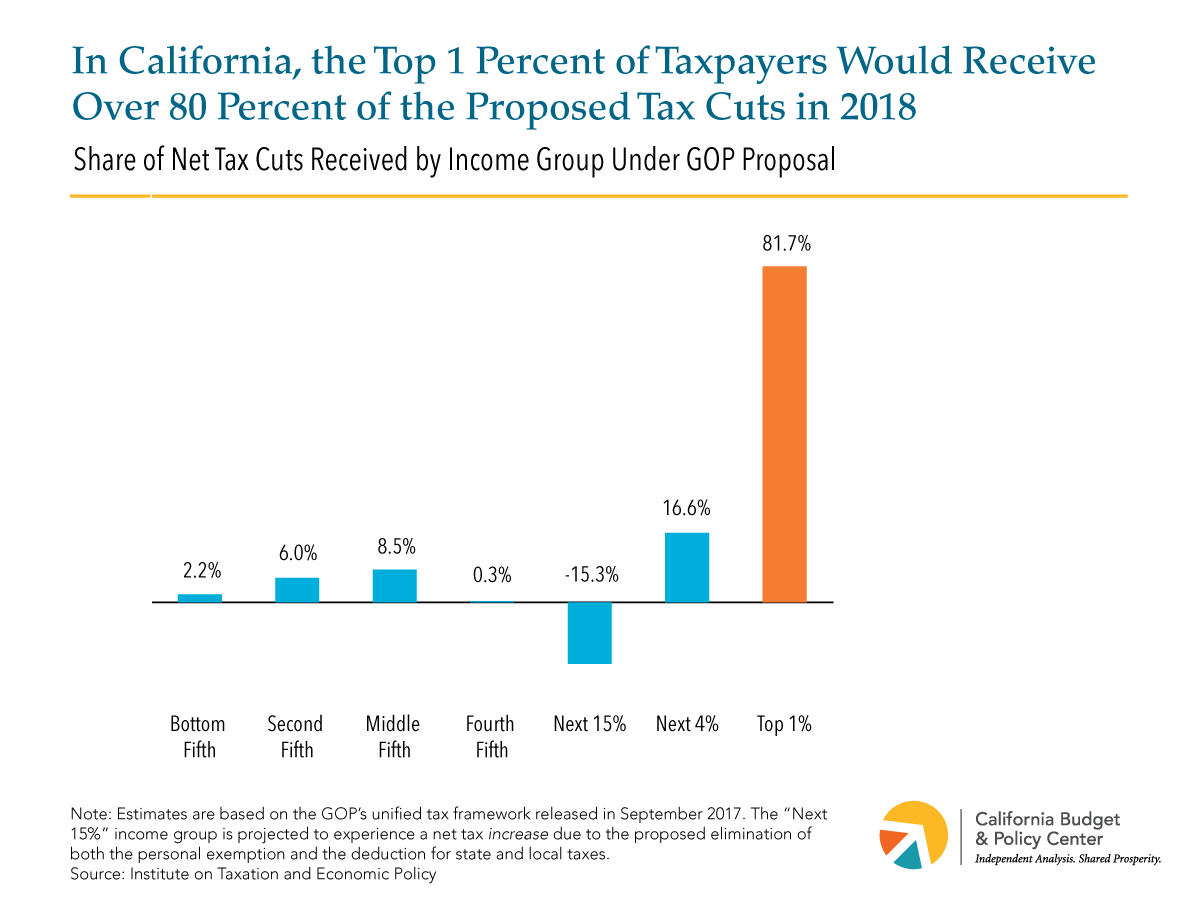

The regressive impacts of this tax framework may be even greater in some states. Here in California, an even larger share of the tax cuts — almost 82 percent — would go to just the top 1 percent of earners in 2018, with another 16.6 percent going to the next 4 percent, and the rest of the benefits spread across the remaining income levels (see chart below). The richest 1 percent of California earners — those making more than $864,900 a year — would receive an average tax cut of $90,160. In contrast, middle-income households — making between $47,200 and $75,500 a year — would receive a much smaller average tax cut of $470, and the lowest income households — those making less than $27,300 a year — would receive a tax cut of $120. For many of these low- and middle-income households the benefits of these marginal tax cuts would likely be offset by significant cuts to federal programs and services including health care, housing, food assistance, and job training assistance, among others.

The latest GOP plan would also come at a huge cost in lost revenues. Estimates of the resulting revenue loss vary from $2.2 trillion to $2.4 trillion over the next decade. While the plan purports to add $1.5 trillion to the federal debt over the next decade, yet-to-emerge details about the plan and likely compromises on some of the plan’s more controversial proposals (such as the elimination of the federal deduction for state and local taxes, widely known as the “SALT” deduction) could result in a much larger increase in federal debt.

The Trump Administration insists that the tax cuts will boost economic growth and pay for themselves, but analysts agree that this scenario is highly unlikely. Rather, in order to minimize the costs of the tax plan, the GOP would likely respond by attempting to further slash entitlement programs like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Medicaid, Medicare, and other parts of the federal budget that include funding for housing, job training, and other assistance. These cuts would likely have negative impacts on the economy by destabilizing economic conditions of millions of households who rely upon those programs to help make ends meet and to access greater economic opportunity.

The combination of GOP tax and budget proposals would be particularly harmful for many Californians and for the state of California.

In terms of budget cuts, the significant cuts to Medicaid and SNAP (Medi-Cal and CalFresh in California) would likely result in reduced or eliminated benefits for millions of Californians with low incomes — over 13 million (34.2 percent) who are enrolled in Medi-Cal and over 4 million (10.8 percent) who receive food assistance through CalFresh.

These cuts would also likely undermine California’s fiscal health, forcing state leaders to choose between destabilizing the state budget by trying to fill fiscal holes as a result of federal tax and budget cuts or, on the other hand, destabilizing vulnerable individuals and communities across the state by reducing benefits.

Some California taxpayers would also see significant increases in their tax bills. For instance, the majority of Californians earning $129,500 to $303,200 annually — which can actually be considered a “middle class” income in the many parts of California where costs of living are significantly higher than much of the country — would see a nearly $4,000 increase in their annual federal tax bills. This increase is largely the result of the repeal of the SALT deduction, mentioned earlier.

In short, the GOP tax and budget plans would increase the tax bills of some Californians, providing minimal tax cuts for many others, while reducing vital public assistance, all in pursuit of providing large tax cuts to the very wealthiest households and corporations.

Congress can still choose a more fiscally and economically responsible path. Instead of providing tax cuts that overwhelmingly go to the wealthiest households and corporations, cutting vital public programs and services, losing trillions of dollars in revenues, and adding significantly to the federal debt, Congress could seek to enact policies that move our nation in the right direction. Federal tax and budget policies should focus on making investments that enable our communities to thrive, help the most vulnerable, and broaden economic prosperity. Any federal tax cuts should be weighted toward those who need them most, and should be revenue-neutral, with lost revenues from tax cuts offset by other revenue increases (new taxes or closed loopholes) that are fairly distributed across the income spectrum.

It will be important to pay attention to which path our elected officials in Washington choose in the coming weeks and months. Their actions may mean that Californians would face the prospect of holding their congressional representatives accountable for decisions that would disproportionately — and negatively — impact our state.

Join our email list!

For the Bay Area Asset Funders Network’s “Public Policy Updates and the Implications on Asset Building for Low-Income Families,” Executive Director Chris Hoene delivered his presentation “The Implications of Federal Budget & Tax Proposals for California.”

Join our email list!

Whether renting an apartment or seeking to purchase a home, Californians face very high housing costs in many parts of the state.

Typical rents for a modest two-bedroom apartment in the areas where nearly two-thirds of Californians live are $1,500 or more per month — a level that is unaffordable for residents with low and moderate incomes.[1] Affordable housing costs are defined by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) as costing 30 percent or less of household income. By HUD’s standard, a family would need at least $60,000 in annual income to afford a monthly rent of $1,500 — an income that would require 110 hours of work per week at the current state minimum wage of $10.50 per hour.[2]

However, rents vary substantially across California. Rents are highest in coastal urban areas, while rents in the Central Valley and in northern inland areas are significantly less expensive, in many cases less than $1,000 per month for a modest two-bedroom apartment. Nonetheless, even these more affordable rents are beyond the reach of many Californians. Rent that is affordable for a full-time minimum-wage worker can be no more than $546 per month — which is lower than HUD’s two-bedroom Fair Market Rent in every part of California.[3] This means that a single parent working full-time at minimum wage cannot expect to afford a modest two-bedroom apartment for her family anywhere in California.

For many middle-income Californians, buying a home is an important goal and part of achieving the “American dream” — but home purchase prices are out of reach for many households with moderate incomes.

Two-thirds of Californians live in areas where the median sales price for a single-family home is $500,000 or more. To purchase a half-million-dollar home while keeping housing expenses to no more than 30 percent of income requires an annual income of roughly $145,000, well over twice the state median household income. In addition to the high annual income required to afford monthly ownership expenses, making a 20 percent down-payment on a home that costs half a million dollars requires $100,000 in savings. Furthermore, nearly 1 in 10 Californians live in a county where the median sales price for a single-family home is $1 million or more — only affordable to households with annual incomes of roughly $244,000 or more, with $200,000 in savings required for a 20 percent down-payment.

Like rents, home sales prices vary greatly throughout the state. In many inland areas of the state, typical home prices are less than $250,000. However, these less expensive areas tend to have substantially lower household incomes than the more expensive parts of the state. In fact, even in the county with the least-expensive median home price (Lassen County), the income required to afford the median-priced home is more than 150 percent of the local median income.

California’s high housing costs create serious burdens for families and individuals with low incomes, who are likely to struggle to afford typical rents even when working full-time. Those with moderate incomes are affected by the state’s high housing costs as well, as high home sale prices put the dream of homeownership out of reach for many. High housing costs can also restrict the ability of families to relocate to access jobs or move close to family, and can push families to live farther from their jobs, leading to longer commutes, which cause increased pollution and reduced time with family. High housing costs also negatively affect the state economy by making it more difficult for employers to recruit workers and deterring individuals from moving to or remaining in California, thus limiting the available labor force and dampening economic growth.

Policy solutions are urgently needed to prevent housing costs from further escalating and to make more housing available that is affordable to lower-income households. Strategies such as subsidizing the development of affordable housing and facilitating more private housing production can help increase the supply of housing, including units affordable to residents with low incomes, thus reducing pressure on costs. These and other policy approaches need to be seriously considered in order to address the negative impacts of California’s high housing costs.

[1] Rents reflect Fair Market Rents (FMR) for 2017, published annually by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development. FMRs are based on the 40th percentile (in a few cases 50th percentile) of gross rents, or rent including utilities, paid by renters within a specific metropolitan area or rural county who moved into their housing units within the past 15 months. FMRs are broadly representative of typical rents paid within a metropolitan area, and are adjusted by HUD to account for expected inflation in housing costs, but they may be lower than the current asking rents for vacant apartments in particularly high-demand cities or neighborhoods within a larger metropolitan area, or in areas where asking rents have been increasing very rapidly.

[2] Minimum wage as of January 1, 2017 for employers with at least 26 employees. See https://www.dir.ca.gov/dlse/faq_minimumwage.htm.

[3] Assumes 40 hours of work per week at the $10.50 minimum wage for employees of large firms as of January 1, 2017. See https://www.dir.ca.gov/dlse/faq_minimumwage.htm.

Join our email list!

A number of current proposals at the federal level, put forth by the Trump Administration and congressional leaders, call for deep spending cuts to many important public services and systems that improve the lives of individuals and families across California. These cuts are proposed at a time when both President Trump and leaders in the House of Representatives have signaled support for major tax cuts that would largely benefit the wealthy and large corporations.

Although federal spending deliberations occur far from California, their outcomes have deep potential impacts right here at home, in every part of our state. In order to shed light on the local importance of federal budget choices, as well as underscore what’s at stake in the votes cast by members of California’s congressional delegation, we are pleased to provide these House district Fact Sheets. They provide district-by-district figures on public services and supports across four areas — food and shelter, health care, income support, and education — along with local information on social and economic conditions.

Click below to get the Fact Sheet for your district. (Find your representative)

Join our email list!

|

|

|

|