Today marks World Maternal Mental Health Day and the start of Mental Health Awareness Month. Maternal mental health (MMH) is vital to the health and well-being of children and families. When mothers feel emotionally healthy and well supported, they are better able to develop strong bonds with their children, which promote children’s physical, mental, and emotional development. Conversely, when mothers experience mental health conditions during pregnancy or after giving birth and do not receive treatment, their health and that of their children, families, and communities are negatively impacted. This blog post discusses the impacts of untreated MMH conditions and highlights strategies to improve outcomes in California.

Untreated Anxiety and/or Depression During Pregnancy and After Childbirth Can Negatively Impact Mothers and Their Children

In California, 1 in 5 women experience pregnancy-related depression — the most common MMH disorder — during pregnancy or the first year following childbirth. That’s about 100,000 women every year. MMH disorders encompass a range of mental health conditions, including depression, anxiety, and postpartum psychosis, although many studies related to MMH disorders focus on depression. Substance use is not included in the definition of MMH disorders, but they sometimes occur together. Research suggests that depression during pregnancy is associated with substance use and that new mothers with postpartum depression may be at a higher risk for substance use. Given this overlap and the limited research on MMH disorders more broadly, this blog post focuses on maternal depression and substance use.

Untreated MMH disorders negatively impact the short- and long-term health outcomes of women and their children and often lead to:

- adverse birth outcomes;

- impaired maternal-infant bonding;

- poor infant growth; and

- childhood emotional and behavioral problems.

In addition, untreated MMH disorders have significant medical and economic costs. The cost of untreated maternal depression is estimated to be $22,500 per mother in lost income and productivity along with associated health costs. With 100,000 California mothers experiencing a MMH disorder every year, “the annual cost of untreated maternal depression in California is estimated at $2.25 billion,” according to the California Task Force on the Status of Maternal Mental Health Care.

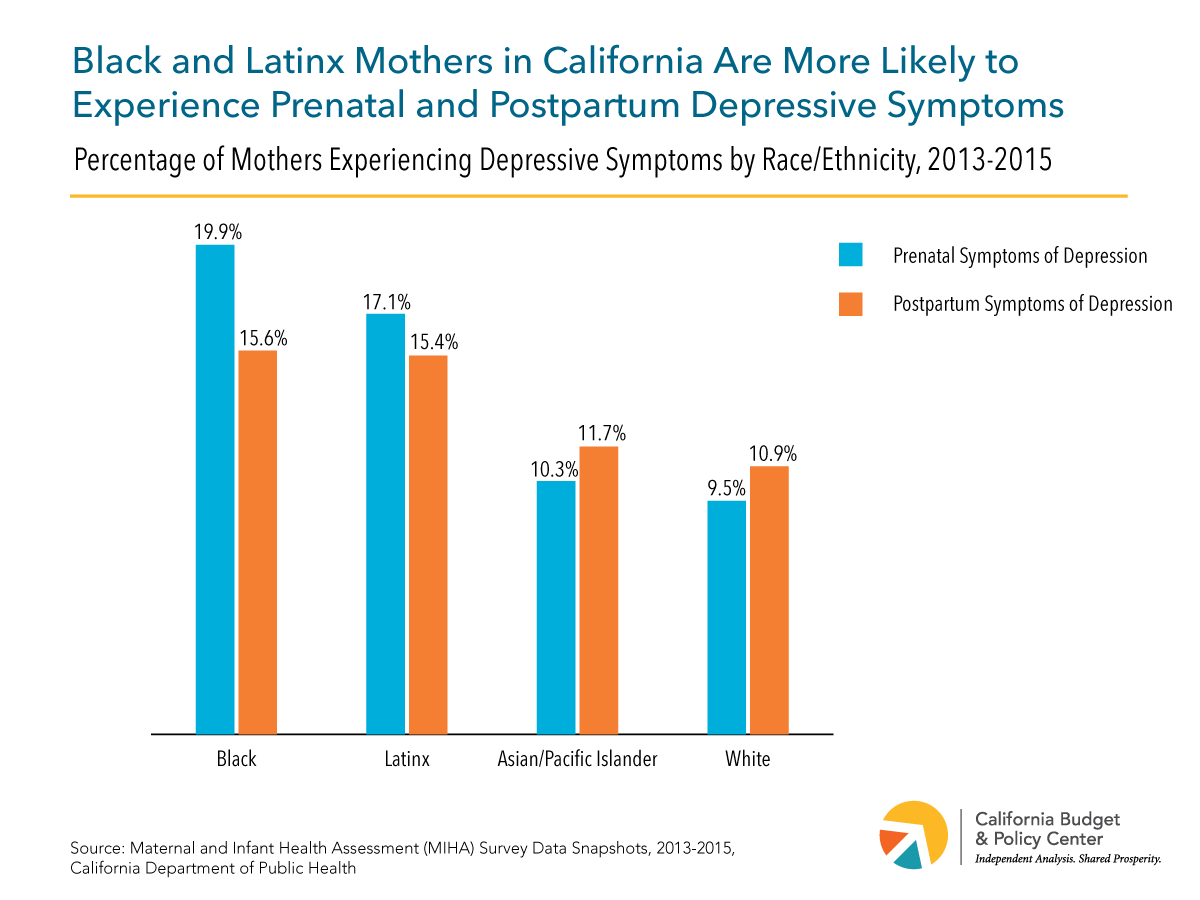

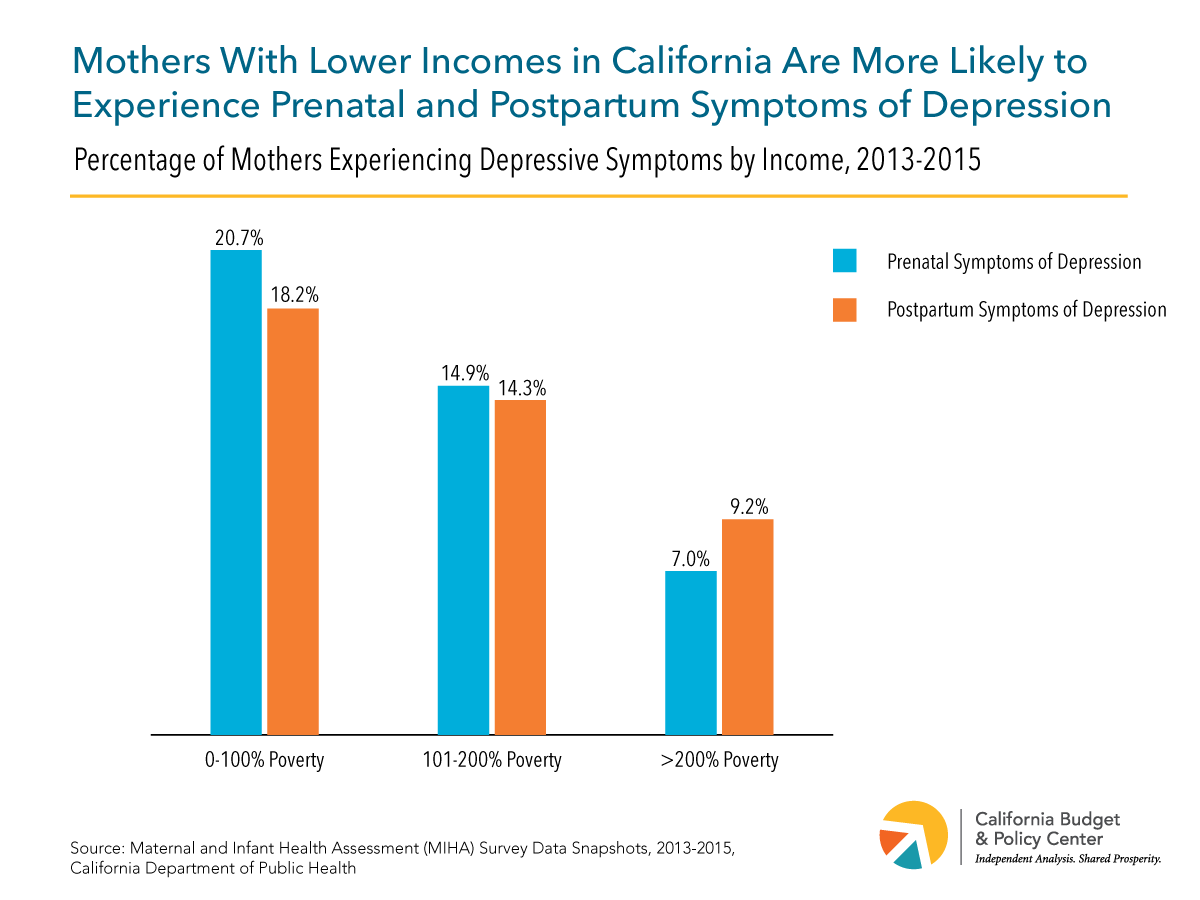

All women are at risk of MMH disorders, but the risk is higher for some women. Socioeconomic status, race and ethnicity, neighborhood, and access to quality health care can impact the likelihood of both experiencing MMH disorders and seeking treatment. One study in California found that women who are black or Latinx and women with low incomes are more likely to have depressive symptoms before and after giving birth. Women who have experienced childhood adversity and stressors during pregnancy are more likely to have depressive symptoms as well. Addressing these factors would help to improve MMH outcomes. Strategies include increasing and improving home visiting services, bolstering income support programs, and improving mental health services and treatment.

Home Visiting Programs Can Help to Improve Maternal Mental Health Outcomes, But There Are Opportunities to Improve the Model

Home visiting programs involve regular visits to expecting parents and parents of young children, typically by a nurse or social worker. These professionals offer training and other assistance aimed at improving maternal and child health and helping parents achieve their education and employment goals. Home visiting programs help to reduce parental stress as well as encourage positive parenting and help to improve child development. Research suggests that home visiting programs have positive effects on MMH and substance use. A study of one home visiting program showed a positive impact on participants’ mental health and coping. An evaluation of a nurse home visitation program showed a decrease in prenatal and postpartum cigarette smoking.

Home visiting programs could do even more to improve MMH. One approach is to integrate mental health supports into home visiting programs. A recent systematic review revealed that 29% to 61% percent of mothers enrolled in home visiting programs across the US experienced depression. Yet, many home visitors do not have adequate training to identify and address the mental health issues experienced by the families they serve. Integrating mental health specialists into the home visiting process would help to address this gap. An evaluation of one home visiting program that incorporated a cognitive-behavioral intervention found that participating mothers showed significantly lower depressive symptoms than those in a control group. Where mental health integration is not possible, community linkages and referral systems could be strengthened to ensure that families receive timely community-based mental health services.

Anti-Poverty Strategies Can Improve Maternal Mental Health Outcomes

Given that poverty is strongly associated with higher levels of depression, one of the most effective anti-depression strategies is an anti-poverty strategy. Poverty is known to heighten exposure to negative life events, job loss, poor housing, dangerous neighborhoods, and conflict with partners, all of which contribute to depressive symptoms. Furthermore, depression is the most common mental health condition among mothers living in poverty, and depression may, in fact, be a result of the hardships mothers experience trying to make ends meet with few resources.

Research on the impact of income support programs on MMH and substance use is limited, but promising. For instance, one study found that working mothers with two or more children whose incomes increased due to the federal Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) reported better overall physical and mental health compared with similar mothers with only one child, who received lower EITC payments. Another study of the 1990 expansion of the federal EITC suggests increasing the EITC may improve mental health for mothers, particularly for married mothers. Results from a more recent analysis using the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System also suggest that the EITC expansion improved self-reported mental health for mothers. Researchers have also found that mothers who received the largest EITC under the 1993 expansion were less likely to drink and smoke during pregnancy.

Anti-poverty strategies such as bolstering the federal EITC and the Child Tax Credit (CTC) help to lift families out of poverty and thereby address the psychological distress that is associated with poverty. In California, these two credits lifted nearly 1.3 million people — including 643,000 children — out of poverty each year, on average, between 2015 and 2017, according to a Center on Budget and Policy Priorities analysis based on the Supplemental Poverty Measure. Increasing the scope and the size of these income support programs could help to mitigate and prevent MMH disorders. Expanding immigrant mothers’ access to these programs would further improve MMH outcomes, particularly because these mothers may be at an increased risk of experiencing MMH disorders due to fear and stress related to heightened immigration enforcement activities.

Current State Budget and Policy Proposals May Also Improve Maternal Mental Health Outcomes

Last year, Governor Brown signed bills into law that aim to increase MMH screenings, which are not routine across health systems, and clinical training to improve MMH treatment. This year, there are new proposals to further improve detection, assessment, and treatment of MMH disorders as well as to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in MMH outcomes, including:

- AB 577 (Eggman) — Medi-Cal: Maternal Mental Health. This bill would extend the duration of Medi-Cal eligibility for postpartum care for an individual who is diagnosed with a MMH condition to one year after giving birth. Currently, Medi-Cal provides coverage for a 60-day period beginning on the last day of pregnancy.

- SB 464 (Mitchell) — California Dignity in Pregnancy and Childbirth Act. This bill would require hospitals and birth centers to implement an implicit bias program for all health care providers who care for expectant and new mothers and their children. By addressing implicit bias among providers, this bill aims to prepare providers to better care for mothers and reduce preventable pregnancy-related deaths. It would also require the Department of Public Health to track and publish data on maternal death and diseases or illnesses.

- AB 1676 (Maienschein) — Tele-Psychiatry. This bill would require health plans and insurers to establish a telehealth consultation program. Telehealth is the use of electronic information and telecommunication technologies to support the delivery of care at a distance. This program would allow providers who treat expectant and new mothers and their children to consult a psychiatrist in real-time regarding the diagnosis and treatment of mental illnesses.

In addition, Governor Newsom’s proposed budget includes expansive proposals that would benefit the health and well-being of mothers and their families. The Governor’s budget proposes to:

- Expand home visiting programs;

- Extend the California Earned Income Tax Credit (CalEITC) to an estimated 1 million additional tax filers (bringing the total to an estimated 3 million);

- Increase the size of the CalEITC credit for many filers who currently qualify for small credits;

- Boost California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids grants (CalWORKs provides modest cash assistance to about 755,000 low-income children while helping parents overcome barriers to employment and find jobs); and

- Increase participation in the Black Infant Health Program, which aims to improve African-American infant and maternal health through group support services and case management.

California Thrives When Mothers Thrive

Addressing the upstream factors that prevent the development of maternal mental health disorders, as well as improving early detection and treatment of these disorders, are critical to improving the health and well-being of mothers and children throughout the state. Improving mental health outcomes is the shared responsibility of multiple stakeholders — health insurers, hospitals, home visitors, community health workers, policymakers, and others. The health of California depends on the health of communities, which thrive when mothers thrive.

Support for this resource was provided by First 5 California.