COVID-19 has disrupted California Community College (CCC) students’ higher education plans, causing many to reduce their course loads or pause their education altogether. The CCCs serve high percentages of students of color and students with low incomes, and drops in enrollment can further narrow educational opportunities and undermine workforce development priorities statewide. While state and federal leaders have enacted policies to mitigate the pandemic’s effects on CCCs, the path forward for community college students requires more long-term investments that address their broader educational and economic needs.1

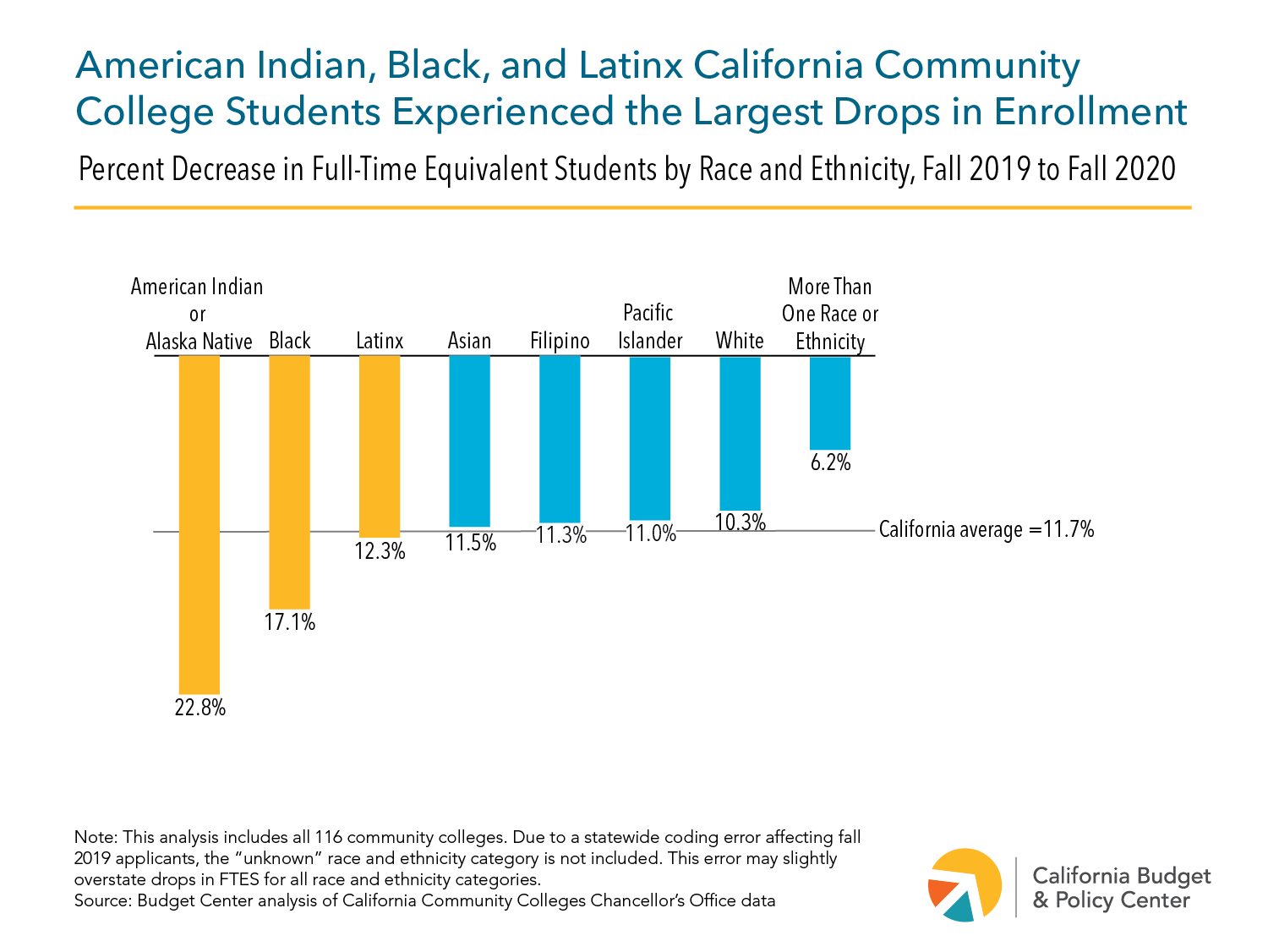

The number of full-time equivalent students (FTES) at the CCCs declined steeply compared to pre-pandemic levels — nearly 12% overall from fall 2019 to fall 2020, the largest year-over-year decrease in over a decade.2 An FTES represents one student who takes a full course load during an academic year.3 The decline in FTES reflects a drop in the number of students, a reduction in student course loads, or both. While all racial and ethnic groups experienced declines, American Indian or Alaska Native students had the largest drop (23%) followed by the drop in Black students (17%). Latinx students fell by 12%, representing over half of the total decline. Reductions from fall 2019 to fall 2020 vary across campuses and student groups. All but six colleges saw declines and ten colleges had drops greater than 25%, and the 19-or-under and the 20-to-24 age groups had declines of approximately 10% and 15%, respectively.

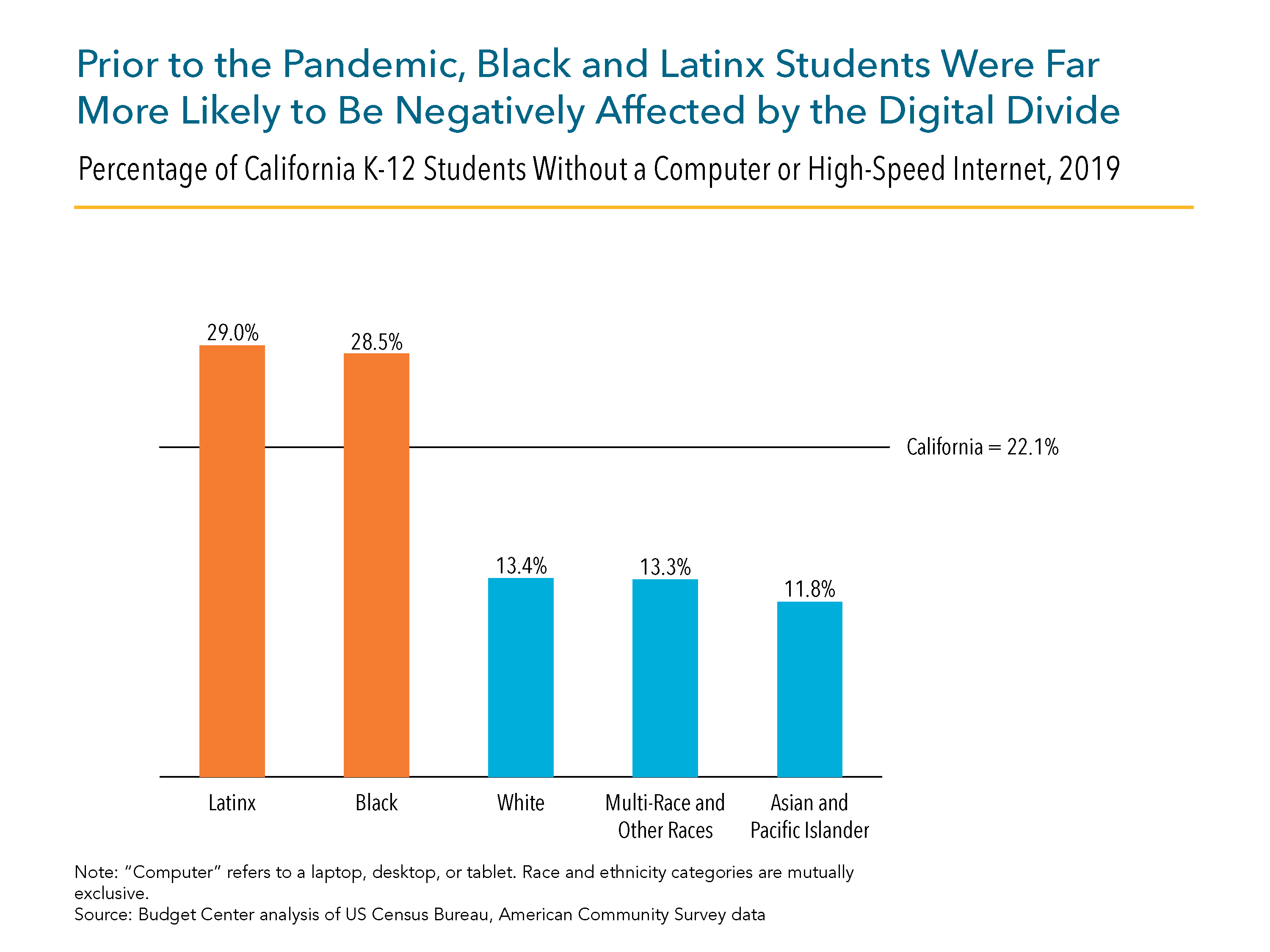

Research shows that the pandemic affected students’ decisions to cancel or delay their education plans.4 Loss of income due to job losses has particularly affected community college students.5 The added financial stress on students’ budgets has disproportionately impacted Black and Latinx students, with many reporting increased food insecurity and having missed rent, mortgage, or utility payments.6 Moreover, online education challenges such as inequitable access to broadband have also made it more difficult for students to continue their enrollment.7

Policymakers can support community college students of color and those with low incomes by pursuing policies centered on robust retention, housing, food, health, access to technology, child care support, completing transfer requirements, and developing career training. State investments in community college students now will pay off as they continue building their careers, futures, and lives across the state, and ensure that a skilled workforce is available to support the California economy.

This work was made possible through the support of Lumina Fund for Policy Acceleration, a sponsored project of Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors.