key takeaway

Despite California’s commitment to funding education through Proposition 98, increased child poverty and budget shortfalls pose substantial challenges.

All California students deserve the opportunity to learn and achieve their goals. Recognizing the critical role schools play in supporting student success, California voters adopted Proposition 98 (Prop. 98), which established an annual minimum funding guarantee for public K-12 schools and community colleges.

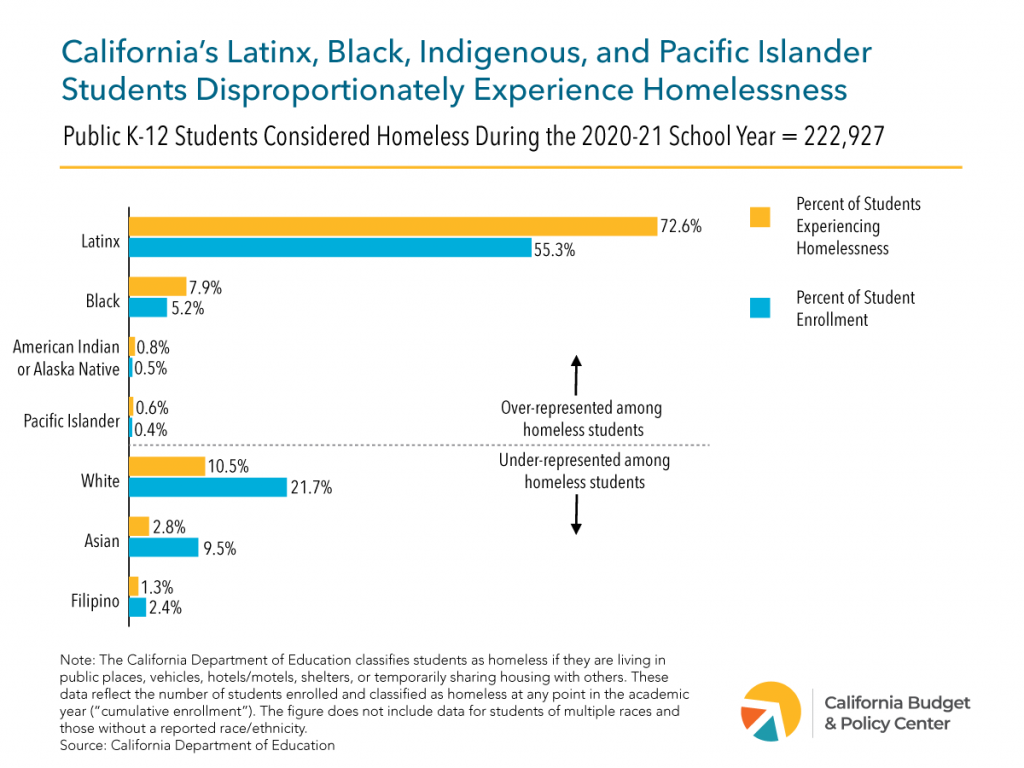

When students and their families struggle to make ends meet, their educational success is put at risk. The poverty rate for children in California more than doubled from 2021 to 2022, suggesting that more support is needed to help families meet their basic needs.

Helping Californians meet those needs while adequately funding K-14 education is challenging when the state experiences a budget shortfall that results from revenues falling far short of projections — as is the case this year. Understanding Prop. 98 and its interaction with the state budget is essential to assess policymakers’ options for addressing the challenges this year’s state budget presents.

What is Proposition 98?

Prop. 98 is a constitutional amendment adopted by California voters in 1988 that establishes an annual minimum funding level for K-14 education each fiscal year — the Prop. 98 guarantee. Prop. 98 funding comes from a combination of state General Fund revenue and local property taxes. Prop. 98 spending supports K-12 schools (including transitional kindergarten), community colleges, county offices of education, the state preschool program, and state agencies that provide direct K-14 instructional programs. While Prop. 98 establishes a required minimum funding level for programs falling under the guarantee as a whole, it does not protect individual programs from reduction or elimination.

How is the Prop. 98 minimum funding guarantee calculated?

Each year’s Prop. 98 guarantee is calculated based on a percentage of state General Fund revenues or the prior year guarantee adjusted for K-12 attendance and an inflation measure.1The inflation measure is either the percentage change in state per capita personal income for the preceding year or the annual change in per capita state General Fund revenues plus 0.5 percent. Since some of this information is not available until after the end of the state’s fiscal year, the Legislature funds Prop. 98 at the time of the annual Budget Act based on estimates of the Prop. 98 minimum funding level.

Once the final Prop. 98 guarantee is determined, the process of reconciling the actual and estimated guarantee is known as “settle up.” If the final Prop. 98 guarantee turns out to be higher than initially estimated, the Legislature must provide additional funding to make up the difference. On the other hand, if the Prop. 98 spending requirement is below the funding level assumed in a budget act, the Legislature has the option to amend the Budget Act to reduce funding to the lower revised minimum Prop. 98 guarantee.2The Legislature also can suspend Prop. 98 for a single year by a two-thirds vote of each house.

To the extent that the Legislature provides funding above the Prop. 98 minimum guarantee, it can increase the following year’s Prop. 98 minimum funding level and state spending required to fulfill the Prop. 98 obligation in future years. In other words, deciding to provide funding above the Prop. 98 minimum guarantee for one budget year can increase the minimum funding level for the subsequent year’s budget and beyond.

What is the Prop. 98 reserve?

California voters approved a constitutional amendment in 2014 that established the Public School System Stabilization Account (the PSSSA) – the Prop. 98 reserve. Constitutional formulas require the state to make deposits into, and withdrawals from, the Prop. 98 reserve. When the state faces a budget problem, discretionary withdrawals from the Prop. 98 reserve may also be made if the governor declares a budget emergency and the Legislature passes a bill to withdraw funds, which can only be used to support K-14 education.

Why is California facing a budget shortfall? And how large is it?

California faces a budget shortfall, also known as a “budget problem,” of tens of billions of dollars. The shortfall is based on estimates of revenues and spending across three fiscal years: 2022-23, 2023-24, and 2024-25 (the fiscal year that begins on July 1, 2024). This three-year period is known as the “budget window.” The main reason for the budget problem is that state revenue collections have fallen short of projections. A large portion of the problem is related to state revenues for the 2022 tax year, which are estimated to be about $25 billion lower than what policymakers expected when they adopted the budget for the current fiscal year last summer.

The extent of the 2022 revenue shortfall only became clear in late 2023 due to the extension of tax filing deadlines for 2022 taxes to November 2023. Because of this delay, state leaders had to finalize the 2023-24 budget last June with much less complete revenue information than usual, and they enacted a budget assuming significantly more revenue for the 2022 tax year than actually materialized.

How does California’s budget problem affect the Prop. 98 guarantee?

Revenue collections falling short of projections not only creates a budget problem for the state, it also means the Prop. 98 minimum funding guarantee for K-14 education is significantly lower than the level assumed in last year’s enacted budget. Based on revenue estimates in the governor’s January 2024 budget proposal, the Prop. 98 minimum funding guarantee dropped by $14.3 billion across the three-year budget window (2022-23 to 2024-25) compared to assumptions made last June.3The amount of state funding required to fulfill the Prop. 98 guarantee across the three-year budget window dropped by $15.2 billion below the Prop. 98 funding level assumed last June. The difference between the state’s funding requirement and the $14.3 billion total decline in the Prop. 98 guarantee reflects estimates in the governor’s January 2024 budget proposal that include a $900 million increase in local property tax revenue, which offsets the $15.2 billion reduction in the state’s portion of the Prop. 98 funding obligation.

Reconciling Prop. 98 spending with revised estimates of the Prop. 98 guarantee can be challenging when the minimum funding guarantee falls — and it is especially difficult if the revised guarantee falls significantly. The current challenge of managing such a large decline in the Prop. 98 minimum funding guarantee is further complicated because the majority of the drop — $9.1 billion — is attributed to the 2022-23 fiscal year, which ended on June 30, 2023.

The Legislature can address the challenge by amending last year’s Budget Act to reduce Prop. 98 funding to the lower revised minimum Prop. 98 guarantee. But, because the state has already allocated 2022-23 dollars to K-14 education, reducing K-14 education funding would be logistically difficult and would significantly impact K-12 schools’ and community colleges’ budgets. On the other hand, maintaining 2022-23 Prop. 98 spending above the minimum funding requirement could boost the state’s funding obligation to meet the Prop. 98 guarantee in 2023-24 and 2024-25.

How does the governor propose to address the budget problem and protect students and educators?

To help address the state budget shortfall, the governor’s January budget proposal assumes a reduction in state funding to the lower revised estimates of the Prop. 98 guarantee over the three-year budget window (2022-23 to 2024-25). To reduce Prop. 98 spending, the governor proposes a combination of spending reductions and discretionary withdrawals from the Prop. 98 reserve.

A significant part of the governor’s plan is an $8 billion reduction in Prop. 98 spending attributable to 2022-23, which would help reduce state General Fund spending to the lower revised Prop. 98 minimum funding level. However, the governor’s proposal would not take away the $8 billion from K-12 schools and community colleges — dollars they received for 2022-23 that have largely been spent. Instead, the governor proposes a complex accounting maneuver that would shift the $8 billion in K-14 education costs — on paper — from 2022-23 to later fiscal years.

Specifically, $8 billion in 2022-23 costs would be spread across five state budgets from 2025-26 to 2029-30 ($1.6 billion per year). Moreover, these delayed expenses would be paid for using non-Prop. 98 funds. In other words, $8 billion in General Fund dollars from the non-Prop. 98 side of the state budget — funds that could otherwise support health, safety net, housing, and other critical services — would be spent on K-14 education but would not count as Prop. 98 spending nor boost the Prop. 98 minimum funding guarantee (the implications of this are discussed below).

In addition, to help pay for existing K-14 education program costs in 2023-24 and 2024-25, the governor proposes making $5.7 billion in discretionary withdrawals from the Prop. 98 reserve. These one-time reserve funds would help support K-14 education in 2023-24 and 2024-25 at the same time that the state reduces General Fund spending required to meet the Prop. 98 minimum funding obligation.

How could the governor’s proposal affect non-Prop. 98 spending?

The governor’s proposal would use non-Prop. 98 resources to make a total of $8 billion in payments to K-14 education starting in 2025-26, but the proposal fails to propose additional revenue or other non-spending cuts to make these payments. Because no additional alternatives are part of the plan, the proposal would create pressure to reduce spending for state budget priorities outside of K-14 education starting in 2025-26.

Shifting Prop. 98 costs to the non-Prop 98 side of the budget creates significant risks to state spending that supports California’s children and families. By creating a future obligation for K-14 education without additional resources to pay for it, the governor’s plan could force reductions in spending for programs such as child care, student aid, and social safety net services that many Californians depend on for support to make ends meet.

How can state leaders address the decline in the Prop. 98 guarantee?

Policymakers have options to address the large decline in the Prop. 98 minimum funding guarantee that include the following:

- Increase state revenues

- Rely more heavily on the state’s Prop. 98 budget reserve

- Consider the Legislative Analyst’s recommendation to use the Prop. 98 reserve to address the decline in the 2022-23 Prop. 98 guarantee

- Reduce or defer state spending for K-12 schools and community colleges

Bottom line: Policymakers can address the decline in the Prop. 98 guarantee without creating pressure to reduce spending for priorities outside of K-14 education. The decline in the state’s Prop. 98 minimum funding guarantee due to state revenues falling short of expectations creates significant challenges for state leaders this year. However, policymakers have options for addressing these challenges, including raising revenues from wealthy corporations and high-income individuals who have ample resources to contribute.

Policymakers can also choose to withdraw more from the state’s Prop. 98 reserve to support K-14 education spending. Relying on Prop. 98 reserve funds alone may not be sufficient to cover all K-14 education expenses for which the state has made commitments. However, policymakers should look to raising revenue and other options to address the decline in the Prop. 98 guarantee that do not harm K-12 schools and community colleges or create pressure to reduce spending for state budget priorities outside of K-14 education.