With COVID-19 cases plummeting and vaccine distribution expanding, businesses are picking up hiring. This is bringing hope that California has turned the corner on the pandemic and is setting a path forward for an economic recovery to finally take hold. But as the state begins to emerge from the recession, lawmakers must keep in mind that their policy choices will determine whether the recovery is inclusive of all people and builds toward an economy that works for everyone. The economic crisis amplified long-standing economic and health inequities, hitting Black, Latinx, and other Californians of color, as well as women, immigrants, and workers paid low wages much harder. These inequities will not disappear as the economy recovers unless lawmakers dismantle racist, sexist, and anti-immigrant barriers to opportunity and make investments that allow all Californians to share in the state’s prosperity.

Low-paying industries continue to face the largest job shortfall. Although the majority of California’s private-sector job gains in March were in the state’s lowest-paying industries, these industries still had 15% fewer jobs in March 2021 than in February 2020. In contrast, moderate- and high-paying industries each had just 5% fewer jobs. In fact, some of the lowest-paying industries still had massive job shortfalls in March: 90% of the arts, entertainment, and recreation jobs that California lost were still gone, as were 61% of the accommodation and food service jobs, and 68% of the “other services” jobs, which include jobs at barber shops, hair salons, and nail salons. Rehiring in these sectors could take time, and it’s possible that not all of the jobs that were lost will come back. For example, to the extent that office workers continue to work remotely after the pandemic ends, restaurants and other businesses near office buildings or downtown hubs may see fewer customers and won’t need as many employees as they did prior to the pandemic. Similarly, if companies continue to hold remote meetings and conferences, hotels and other businesses serving business travelers may not need to rehire as many workers.

The “official” unemployment rate significantly understates California’s jobs crisis, highlighting the need to track broader measures. The unemployment rate published monthly by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) is typically used to assess conditions for workers. However, this measure has substantially understated the pandemic jobs crisis, prompting many economists to use alternative measures of unemployment that include people who want to work, but left the labor force after losing their jobs because other jobs weren’t available or weren’t safe, or because they had to care for children schooling from home or for sick family members (see technical note). Based on one such broader measure, about 1 in 10 Californians were out of work in March 2021 (10.3%) — notably higher than California’s “official” unemployment rate of 8.3%. In fact, a total of about 2 million Californians were unemployed in March based on this expanded measure — over 400,000 more than those counted in the official measure. Like the official unemployment rate, this broader measure has fallen significantly from its peak last spring, but remains about twice as high as it was in February 2020, just before the recession began.

Black and Latinx Californians remain considerably more likely to be out of work. One year into the recession, 15.3% of Black Californians and 13% of Latinx Californians were unemployed, based on the broader measure described above. This is considerably higher than the 9.7% unemployment rate for white Californians and 8.6% rate for Asian Californians. (Due to data limitations, it is not possible to present monthly unemployment figures for other Californians of color, such as Pacific Islanders, American Indians, and people who are multi-racial, or to disaggregate the data further to show, for example, the diverse range of experiences within Asian Californians. National data, however, show high unemployment among American Indians and Pacific Islanders during the recession.) Women were also more likely to be out of work than men, and national research has suggested that at least some of this disparity reflects mothers leaving the labor force because of remote schooling or child care responsibilities during the pandemic. Immigrants — who experienced greater job losses when the pandemic first began — were less likely to be unemployed one year into the recession than Californians who are not immigrants.

Layoffs during the pandemic reduced the earnings of the majority of Black and brown Californians. More than 60% of Black and Latinx households lost earnings during the pandemic, compared to well under half of Asian and white households. (Due to data limitations, it is not possible to present monthly unemployment figures for other Californians of color, such as Pacific Islanders, American Indians, and people who are multi-racial, or to disaggregate the data further to show, for example, the diverse range of experiences within Asian Californians.)

While striking, these job and income inequities are not new for Black and brown Californians; they are rooted in our nation’s history of structural racism. Even before the current jobs crisis, Black and American Indian Californians were about twice as likely to be unemployed as white Californians, and Latinx women were about one-and-one-half times as likely to be unemployed as white women. In addition, Californians of color — particularly women and those who are American Indian, Black, Latinx or Pacific Islander — earned considerably less than white men before the pandemic, even when working full-time, year-round. (See the employment and earnings component of the Women’s Well-Being Index for more information.) These inequities are the product of past and present racist policies and practices, including housing segregation, the underfunding of predominantly Black and brown public schools, mass incarceration, and employment discrimination — all of which make it difficult for many people of color to access good jobs and be paid fair wages.

Policymakers Must Create an Inclusive Recovery that Builds Toward a More Equitable Economy

There is growing optimism that a recovery from the economic crisis is finally underway for California. But the employment and income inequities that widened during the recession for Black and brown Californians, women, immigrants, and workers paid low wages will likely not disappear on their own as the state’s economy improves. To avoid returning to the deeply inequitable economy that predated the pandemic, state and federal lawmakers must make policy choices that foster an inclusive recovery and lay the foundation for a more equitable economy – one that ensures that Black, Latinx, and other Californians of color, women, immigrants, and Californians with low incomes share in the state’s economic gains and vast wealth.

To do this, federal policymakers must first not cut off too soon the economic supports, such as enhanced federal unemployment benefits, that are helping families meet basic needs during the crisis. Doing so would harm Black and Latinx Californians and others who continue to be hit hard by the pandemic and recession. In addition, state policymakers should provide much more financial support to undocumented Californians and their families, who have been excluded from nearly all economic relief during the pandemic.

Beyond responding to the immediate crisis, policymakers must better prepare for the next recession, for example by reforming the unemployment insurance system to ensure that workers receive the support they need when they lose work. Lawmakers also must prioritize equity in all policies and institutions so that all people can thrive. Some California current efforts that would help include:

- Establishing an independent body to address systemic and institutional racism in order to ensure that the state plays a more active role in dismantling racial inequities that hold back Californians of color.

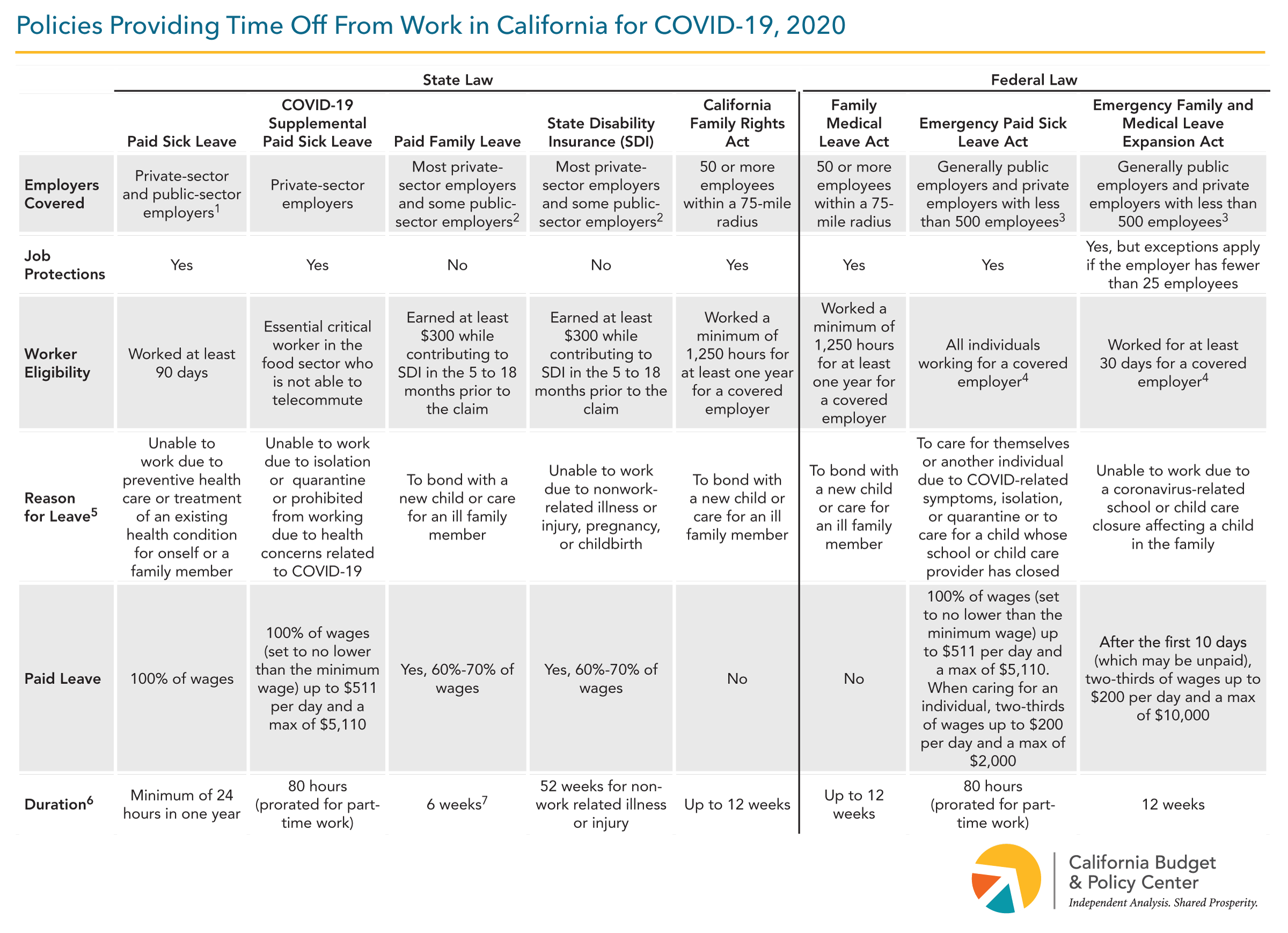

- Investing in the state’s child care infrastructure and making paid family leave more accessible to people with low earnings to help reduce employment and pay inequities between women and men due to family care responsibilities.

- Ensuring basic workplace protections, such as through the Health and Safety for All Workers Act and the Garment Worker Protection Act, as well as ending exclusions from public supports, such as full-scope Medi-Cal and the California Food Assistance Program in order to improve conditions for immigrants.

Lawmakers must also invest in better publicly accessible data because economic and health equity cannot be achieved if information on inequities affecting the lives of Californians is not collected. Major federal data, including monthly unemployment figures, do not allow for sufficient disaggregation for racialized communities or for intersectional analyses. In fact, the experiences of LGBTQ+ people are almost entirely absent from federal surveys. This renders the experiences of many communities invisible, making it difficult to show with data where policy change is needed or can be targeted to better serve Californians, especially LGBTQ+ Californians and many Californians of color.

Policies that address the economic and health needs of communities and dismantle structural racism, sexism, and other forms of discrimination can help California emerge from the pandemic recession to a more equitable economy where all Californians share in the state’s prosperity.

Technical Note

The “official” unemployment rate reported each month by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) is widely understood to have underreported the extent of joblessness during the pandemic. Consequently, many economists, including those at the Federal Reserve Board and the President’s Council of Economic Advisors, have published adjusted unemployment rates that are likely more accurate than the official BLS measure.

This report presents unemployment rates with two adjustments that should result in a more accurate measure of joblessness. Specifically, these unemployment rates:

- Include people who were likely unemployed, but misclassified as employed. The BLS believes that during the COVID-19 recession a large number of workers who reported being employed, but absent from work, were in fact on temporary layoff and should have been counted as unemployed. Each month since March 2020, the BLS has estimated how many workers may have been misclassified in this way and reported what the national unemployment rate would have been had these workers been counted as unemployed. This report follows the BLS methodology for identifying potentially misclassified workers, which is described here, and adds these workers to the number of unemployed to calculate adjusted unemployment rates.

- Include people who were not counted in the labor force because they did not look for work recently, but who want a job. To be officially counted as unemployed, workers must have made specific efforts to find employment in the past four weeks. If they did not, then they are counted as not in the labor force even if they want to work. This means that they are not included in the unemployment rate. However, many workers who lost their jobs during the COVID-19 recession did not search for work even if they wanted a job, particularly at the beginning of the recession when state-mandated business closures meant that there were far fewer jobs available. Moreover, California temporarily waived the requirement that unemployed workers search for jobs each week in order to receive unemployment benefits, recognizing that whole sectors of the economy had to be shut down in order to protect the public’s health. This analysis adds to the number of unemployed people who did not look for work in the past four weeks as long as they reported wanting a job, being available for work, and having looked for employment in the past year. This is a more conservative adjustment than the one made by the Federal Reserve Board, which counts all people who dropped out of the labor force since February 2020 as unemployed.