California’s subsidized child care providers offer vital early learning and care options for families struggling to make ends meet. These early educators — who are primarily women and disproportionately women of color — deserve fair and just wages for essential work that helps children learn and grow while parents are working or going to school to support their families.

Despite providers’ critical role in nurturing children and assisting families, state leaders have failed to consistently and adequately increase provider payment rates in recent years. Without sufficient payments, child care providers are unable to offer early educators fair wages, struggle to keep pace with the rising statewide minimum wage, and can’t afford the increasing price of food and supplies. Ultimately, California providers and families suffer when affordable child care is limited in their communities because of policymakers’ lack of investment.

How Are Subsidized Child Care Providers Paid in California?

Subsidized child care providers are paid in one of two ways in California: 1) by accepting vouchers from families or 2) by contracting directly with the state. Providers who accept vouchers are reimbursed by the state based on the Regional Market Rate (RMR) Survey. The RMR survey — administered every two to three years — provides “rate ceilings” based on provider setting and the age of the child for all 58 California counties. The rate ceiling is the highest payment a provider can receive from the state for the care of a child. Providers who contract directly with the state are paid based on a Standard Reimbursement Rate (SRR). The SRR is adjusted to reflect the additional cost of serving certain children.1In 2018-19, policymakers also increased the Standard Reimbursement Rate adjustment factors for certain higher-cost groups of children, such as infants and children with disabilities. However, some (but not all) of these adjustment factors were eliminated in the 2021-22 budget agreement as part of the transition to a single reimbursement rate system for subsidized child care providers. See Assembly Bill 1808 (Committee on Budget, Chapter 32, Statutes of 2018), https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=201720180AB1808; and Assembly Bill 131 (Committee on Budget, Chapter 116, Statutes of 2021), https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=202120220AB131. Moreover, beginning in 2022-23, state law requires an annual cost-of-living adjustment to the SRR, although the Legislature may suspend it for a given fiscal year.

Payment Rates for Voucher-Based Child Care Providers Are Not Keeping Pace Across 58 Counties

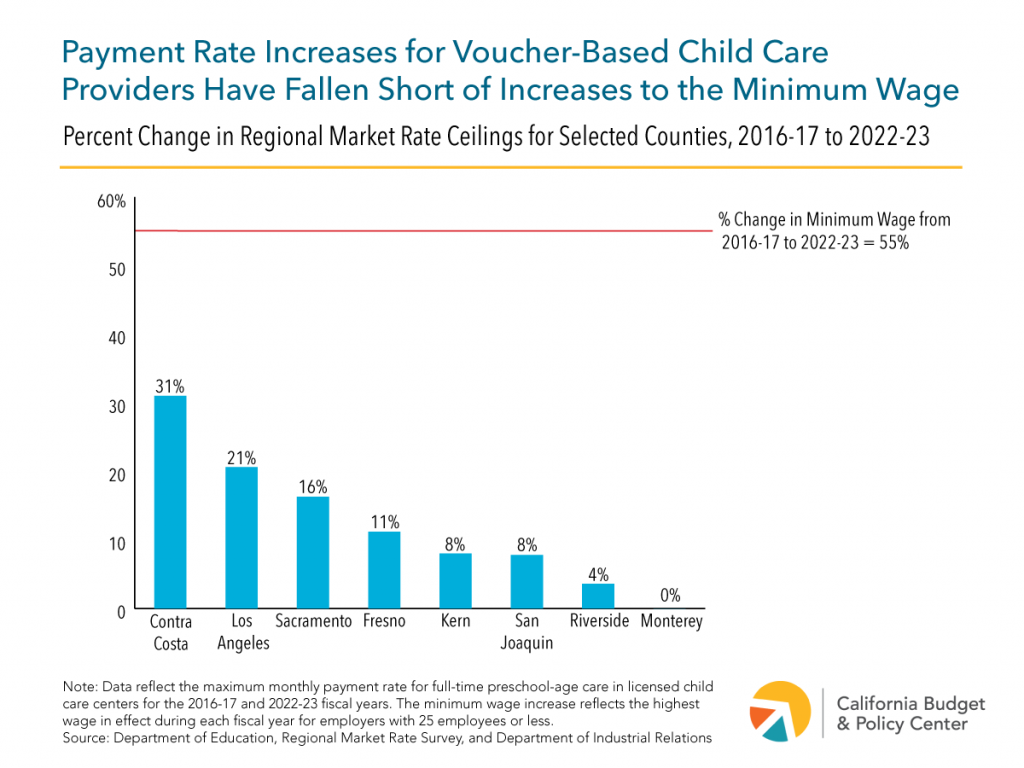

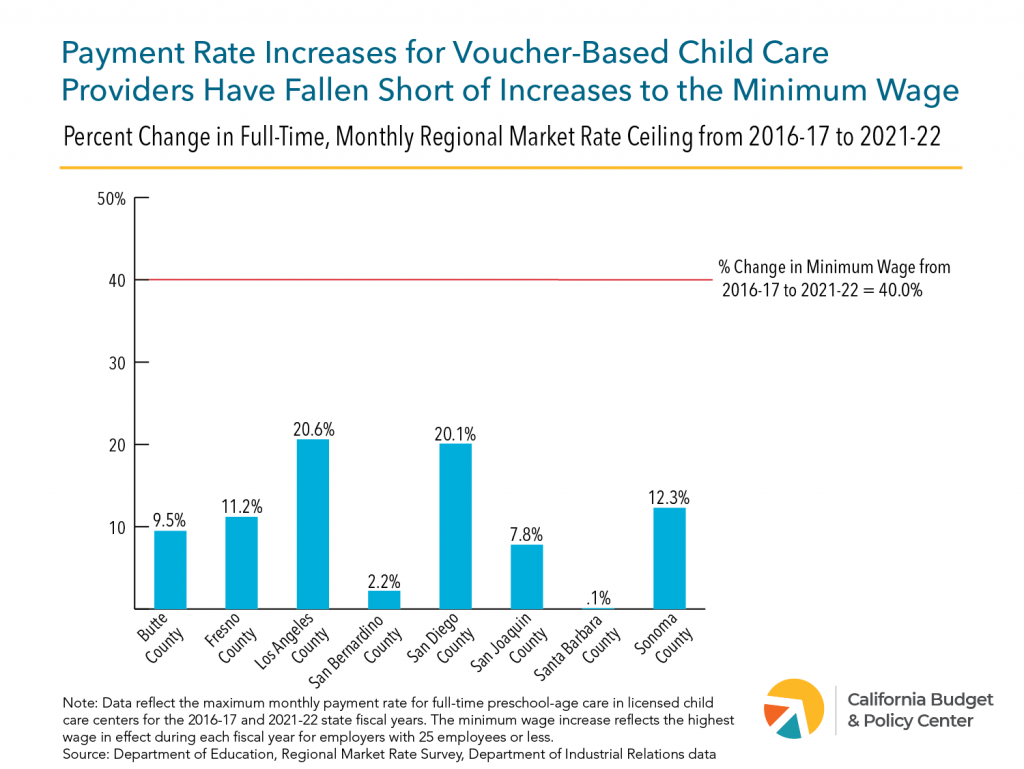

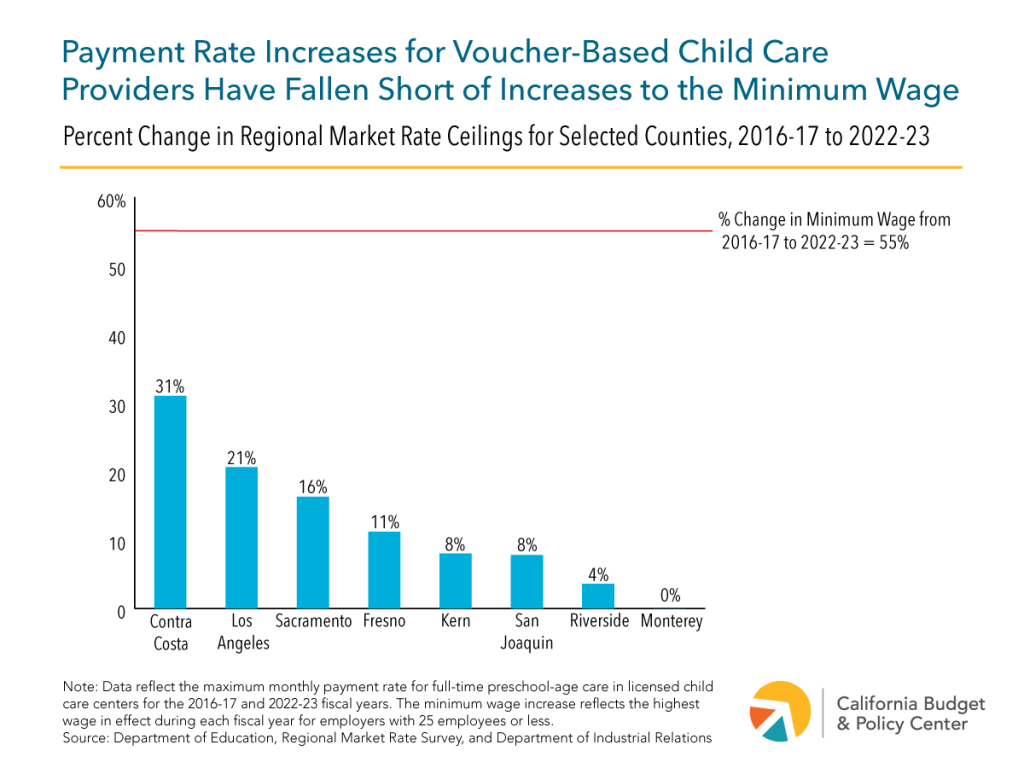

State leaders have updated voucher-based payment rates for child care providers just twice since the 2016-17 state fiscal year. During this same period, the state law requiring annual increases to the statewide minimum wage went into effect, raising the wage by 55% from 2016-17 to 2022-23 and increasing costs for providers.2Calculations are based on the minimum wage for employers with 25 employees or less. Senate Bill 3 (Leno, Chapter 4, Statutes of 2016), https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201520160SB3.

The rate ceilings for child care providers across all 58 counties generally have not kept pace with the rising minimum wage even after the most recent increase to payment rates enacted in 2021-22. In the state’s most populous county — Los Angeles — payment rates for licensed centers caring for preschool-age children increased by less than half as much as the statewide minimum wage. Providers in some counties, such as Riverside County, saw miniscule rate increases of less than 5%. And in 27 counties, due to weaknesses in the rate-setting methodology, licensed centers have not received a single rate increase for care for preschool-age children since 2016-17.3Market rate surveys collect data on the tuition and fees that families can afford to pay for child care in a geographic area. These rates typically do not cover the true cost of care, as many providers supplement tuition and fees with other sources of revenue, such as grants or donations. See Bipartisan Policy Center, The Limitations of Using Market Rates for Setting Child Care Subsidy Rates (May 2020), 4-6, https://bipartisanpolicy.org/report/the-limitations-of-using-market-rates-for-setting-child-care-subsidy-rates/

State Rate for Contract Providers Doesn’t Match Rising Child Care Business Costs

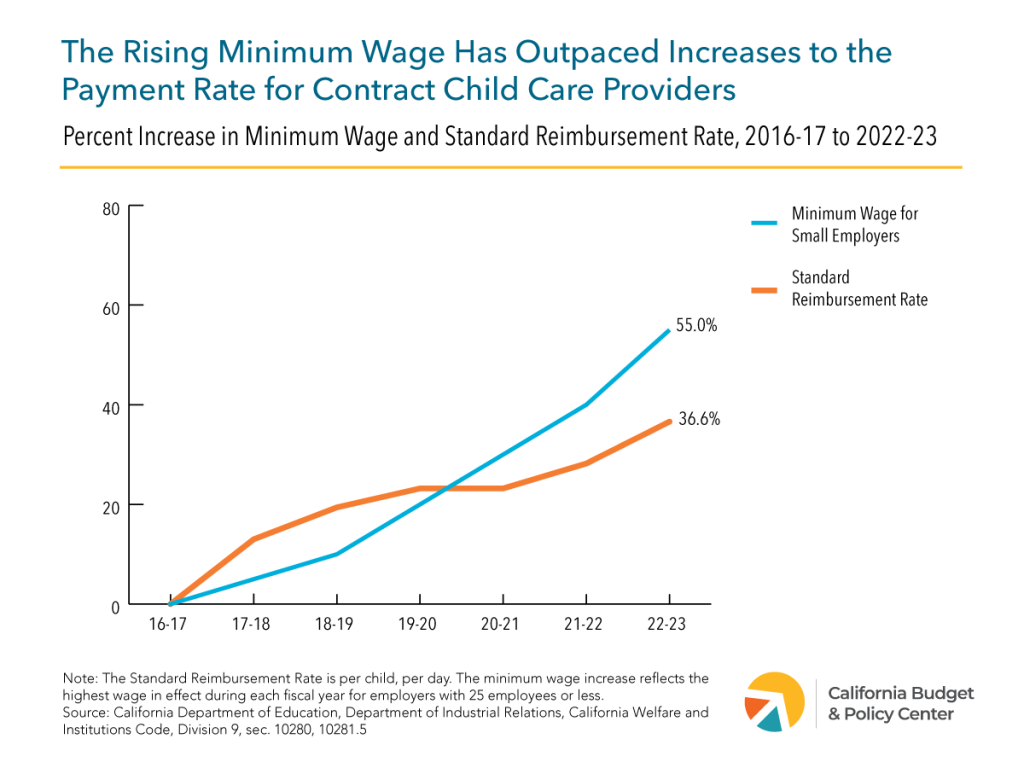

Policymakers have not consistently updated the SRR each year so that contract providers can keep pace with rising staff costs and the increasing price of food and supplies. From 2016-17 to 2022-23, the SRR increased by 36.6%, falling short of the 55% increase in the state minimum wage.

Even though contract-based providers are required to meet more program standards than voucher-based providers do, the payment rate is lower than the RMR ceiling in many counties, illustrating a key problem with the state’s bifurcated rate system. To correct for this, policymakers included a provision in the 2021-22 budget agreement to reimburse contract-based providers with either the SRR or the rate for voucher-based providers, whichever is higher.4Assembly Bill 131 (Committee on Budget).

Child Care Providers Urgently Need a Substantial Pay Raise

Child care provider rates are inadequate and further destabilize the state’s early care and learning system. Policymakers should significantly increase rates in 2023-24 to ensure child care providers can keep up with costs and continue to offer invaluable care to children and families. Doing so would offer needed relief to providers and support the longer-term implementation of a new rate system that will reflect the actual cost of providing care, including paying educators fair wages.

To fully and consistently fund these critical investments in child care, state leaders will have to develop solutions that raise ongoing revenues. One option is to scale back or eliminate costly tax breaks that provide outsize benefits to wealthy people and profitable corporations. Each dollar that goes to these poorly targeted tax breaks is a dollar that is not available to bolster core state services — such as subsidized child care. Moreover, the State Appropriations Limit (“Gann Limit”) may be a barrier to boost investments in child care and other public services. Policymakers should work to remove or significantly reform this spending cap so the state can plan and make bold investments that help families be healthy and thrive.