Introduction

Over many years, California lawmakers and voters adopted harsh, one-size-fits-all sentencing laws that prioritized punishment over rehabilitation, led to severe overcrowding in state prisons, and disproportionately impacted Californians of color.

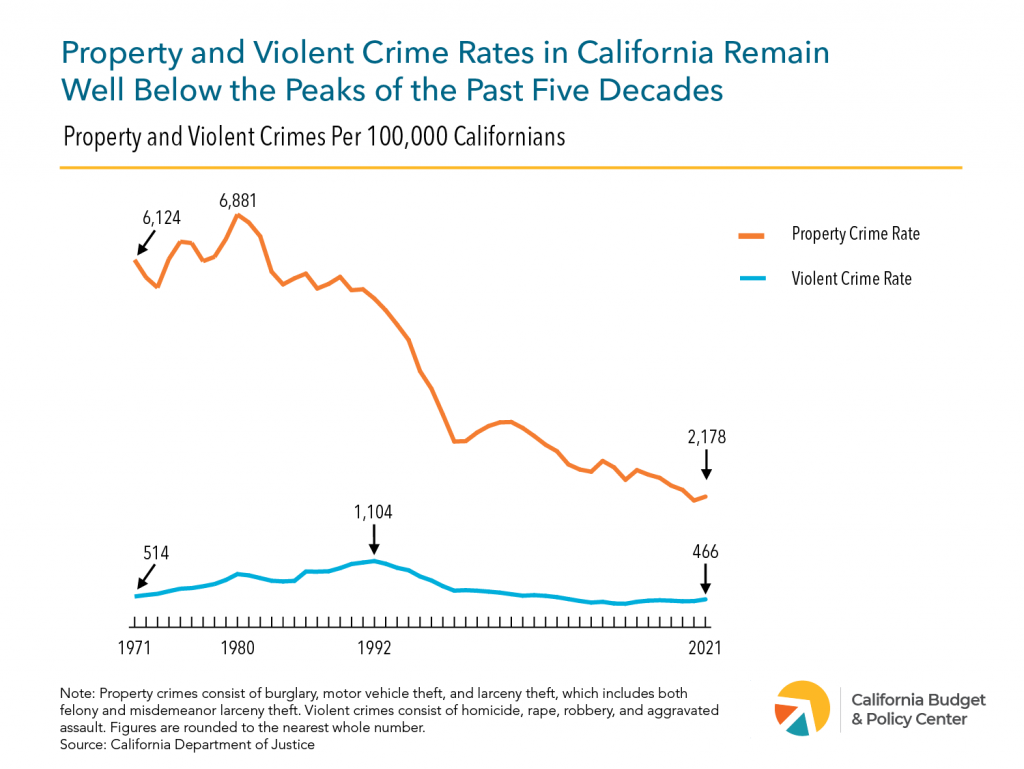

California began reconsidering its “tough on crime” approach in the late 2000s. Multiple reforms were adopted as prison overcrowding reached crisis proportions and the state faced lawsuits filed on behalf of incarcerated adults. These reforms worked as intended: The number of adults serving sentences at the state level fell from a peak of 173,600 in 2007 to around 90,000 today. Meanwhile, violent and property crime rates in California remain well below historical peaks.

A key justice system reform was Proposition 47, which passed with nearly 60% support in 2014. Prop. 47 reduced penalties for six nonviolent drug and property crimes from felonies to misdemeanors. As a result, state prison generally is no longer a sentencing option for these crimes. Instead, people convicted of a Prop. 47 offense serve their sentence in county jail and/or receive probation.

Prop. 47 also requires the state to calculate prison savings due to reduced incarceration and use those dollars to reduce recidivism and support crime victims. Since 2016, over $800 million in Prop. 47 savings has been allocated across the state for behavioral health treatment and other critical services that promote community safety.

However, interest groups opposed to justice system reforms qualified Prop. 36 for the November ballot. Their goal is to increase punishment for drug and theft crimes in California, including by reversing key provisions of Prop. 47. Major donors to Prop. 36 include Walmart ($2.5 million), Home Depot ($1 million), Target ($1 million), In-N-Out Burger ($500,000), the California Correctional Peace Officers Association ($300,000), and Macy’s ($215,000).

Stay in the know.

Join our email list!

Prop. 36 Would Increase Penalties for Several Drug and Theft Crimes

Prop. 36 would amend state law to increase penalties for several drug and theft crimes. These changes would disproportionately impact Californians of color given racist practices in the justice system as well as social and economic disadvantages that communities of color continue to face due to historical and ongoing discrimination and exclusion.

Prop. 36 would increase penalties for drug crimes in multiple ways. Key drug-related provisions of the measure include the following:

- Creating a new process allowing prosecutors to charge people with a “treatment-mandated felony” for possession of illegal drugs.

- Requiring people who sell large quantities of certain drugs, including substances containing fentanyl, to serve their term in state prison.

- Requiring people convicted of unlawfully possessing fentanyl while armed with a loaded gun to serve up to four years in state prison.

Prop. 36 also would increase penalties for theft crimes in multiple ways. Key theft-related provisions of the measure include the following:

- Allowing people with multiple prior theft convictions to be charged with a felony if they subsequently commit petty theft or shoplifting.

- Creating sentencing add-ons (“enhancements”) that apply to people convicted of a felony involving damaged or stolen property valued at more than $50,000.

Prop. 36 Would Drive Up State Prison Spending and Create Unfunded Costs at the State and Local Levels

By increasing punishment for several drug and theft crimes, Prop. 36 would create substantial new costs — including for incarceration and the court system — at the state and local levels. However, the measure would provide no new revenue to pay for these expenses.1Prop. 36 states that a person charged with a “treatment-mandated felony” may receive, if eligible, relevant Medi-Cal or Medicare services that are delivered through a court-ordered treatment program. (Medi-Cal is supported with state and federal funding; Medicare is funded solely by the federal government.) Therefore, some federal funding could be available to support services for people who are charged with a treatment-mandated felony and are eligible for Medi-Cal or Medicare. However, the state would have to pay a portion of any Medi-Cal services delivered, and Prop. 36 would not provide any revenue to offset those new state costs. In addition, the costs associated with treatment-mandated felonies represent only part of the substantial state and local criminal justice costs that Prop. 36 would create — costs for which the measure provides no new funding. State and local leaders would face the prospect of curtailing funding for existing public services in order to make room in their budgets for the unfunded costs imposed by Prop. 36.

While Prop. 36 would clearly burden public budgets, the magnitude of the impact is uncertain. Cost estimates have been developed by the nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO) as well as by Californians for Safety and Justice (CSJ), a leading statewide public safety advocacy group. Both organizations suggest that the cost of Prop. 36 could be substantial, although the LAO’s estimates are significantly lower than CSJ’s.2The substantial gap between these two sets of estimates is likely the result of different assumptions, methodologies, and/or data sources adopted by each organization.

Specifically:

- The LAO estimates that the ongoing increase in state criminal justice costs would likely range from several tens of millions of dollars to the low hundreds of millions of dollars. This estimate reflects a larger prison population — which could grow by “around a few thousand people” — as well as an increase in state court workload.

- In addition, the LAO estimates that ongoing local criminal justice costs would likely increase by tens of millions of dollars due to Prop. 36. This estimate reflects larger county jail and community supervision populations — which, combined, could rise by “around a few thousand people” — as well as higher costs for courts, prosecutors, public defenders, and county agencies like probation and behavioral health departments.

- In contrast, CSJ projects that Prop. 36 would lead to much higher costs. CSJ estimates that combined state and local costs would rise by around $4.5 billion ongoing. For example, CSJ suggests that more than 32,000 additional people would be sentenced to state prison within seven years. CSJ also assumes that over 31,000 additional people would serve one-year sentences in jail each year. These projected increases in incarceration are much higher than what the LAO’s analysis suggests.

Regardless of the magnitude of the costs created by Prop. 36, the result would be the same: elected officials would face difficult choices about how to accommodate these new unfunded costs in their budgets. Such choices could disproportionately harm Californians with low incomes and communities of color depending on which current state and local services were affected by funding reductions.

These tough decisions would come at a time when state and local leaders are already struggling to keep their budgets balanced and ensure ongoing support for core services. For example, the 2024-25 state budget package relies heavily on borrowing from future budgets and only temporarily increases revenues — decisions that could compromise the state’s ability to sustain core programs as well as stall much-needed investments in the coming years. The new unfunded costs imposed by Prop. 36 would make it even more challenging for state leaders to sustain support for core services and maintain a balanced budget.

In addition, Prop. 36 would reverse the modest progress that California has made in controlling state prison spending. Justice system reforms, including Prop. 47, have reduced the prison population and allowed state leaders to end private-prison contracts, begin closing state-owned prisons, and bend the prison cost curve. In fact, prison spending is billions of dollars lower today than it would be absent these reforms. These freed-up dollars have been redirected to critical state services that rely on the state’s General Fund for support.

Moreover, the prison system’s “footprint” on the state budget has been shrinking as reforms have taken effect. The budget of the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) comprised over 9% of total General Fund spending in 2013-14 — the fiscal year before Prop. 47 was approved in November 2014. Since then, CDCR’s share of the state budget has dropped to less than 7% as prison spending has grown more slowly than overall state expenditures.

Still, state correctional spending remains too high, and more work is needed to further downsize California’s costly and sprawling prison system. However, the trend has been moving in the right direction, and the significant gains that have been made over the last decade would be eroded if Prop. 36 is approved by voters.

Prop. 36 Would Reduce State Funding for Behavioral Health Treatment and Other Critical Services

By passing Prop. 47 in 2014, voters not only reduced penalties for several low-level crimes and lowered the prison population — they also required state prison savings from Prop. 47 be used for services that reduce crime, support youth, and help crime victims heal. To date, Prop. 47 savings — as calculated by the Department of Finance — exceed $800 million, or around $90 million per year, on average.

Prop. 47 savings are annually deposited into the Safe Neighborhoods and Schools Fund and used as follows:

- 65% for behavioral health services — which includes mental health services and substance use treatment — as well as diversion programs for individuals who have been arrested, charged, or convicted of crimes. These funds are distributed as competitive grants administered by the Board of State and Community Corrections.

- 25% for K-12 school programs to support vulnerable youth. These funds are distributed as competitive grants administered by the California Department of Education.

- 10% to trauma recovery services for crime victims. These funds are distributed as competitive grants administered by the California Victim Compensation Board.

Prop. 47 savings are invested in a broad range of programs that support healing and keep communities safe. For example, a recent evaluation shows that people who received Prop. 47-funded behavioral health services and/or participated in diversion programs were much less likely to be convicted of a new crime. People who enrolled in these programs had a recidivism rate of just 15.3% — two to three times lower than is typical for people who have served prison sentences (recidivism rates range from 35% to 45% for these individuals). These programs are also successful in reducing homelessness and promoting housing stability, with a 60% decrease in the number of participants experiencing homelessness by the end of the program compared to when they enrolled.

Because Prop. 36 would undo key provisions of Prop. 47, the annual state savings from Prop. 47 would decline. The LAO estimates that this reduction would likely be in the low tens of millions of dollars per year, whereas CSJ projects that the state savings would be entirely eliminated.

The most recent estimate of Prop. 47 savings is $95 million, as reflected in the 2024-25 state budget. If Prop. 36 had been in effect this year, these savings would have been tens of millions of dollars lower (based on the LAO’s analysis) or entirely eliminated (based on CSJ’s assessment). Either way, there would be substantially less funding for services that reduce crime, support youth, and help crime victims heal. In other words, Prop. 36 would shift tens of millions of dollars or more each year from behavioral health treatment and other critical services back to the state prison system.

Prop. 36 Could Push More Californians Into Homelessness

Prop. 36 could worsen homelessness in California by pushing more residents into the carceral system, further exacerbating the deep link between homelessness and incarceration. While the lack of affordable housing is the primary cause of homelessness, this detrimental outcome is intensified by incarceration as formerly incarcerated people are nearly 10 times more likely to experience homelessness than the general population.

Californians leaving incarceration often face significant obstacles to securing long-term, stable housing, which is essential for reconnecting with support networks, finding employment, and maintaining health. Without proper housing, which Prop. 36 does not account for or ensure, formerly incarcerated individuals are more likely to recidivate and resort to survival crimes, perpetuating the harmful cycle.

A recent statewide homelessness study found that nearly 1 in 5 unhoused Californians (19%) entered homelessness directly from an institutional setting, primarily a jail or prison. Additionally, fewer than 20% of people leaving jail or prison had support finding housing upon their release. Prop. 36 does nothing to address this need and instead reverts funding from existing programs that help unhoused individuals with conviction histories connect with housing, behavioral health treatment, and other necessary services needed to reintegrate.

Further, Prop. 36 fails to follow effective, evidence-based interventions that successfully help individuals obtain and sustain mental health and substance use treatment, with housing as a foundational component. The initiative allows certain people arrested for drug possession to admit guilt (or plead no contest) and have their charges dismissed if they complete court-ordered treatment.

However, completing a treatment program is especially challenging for individuals experiencing housing instability or homelessness. Not having a home causes severe stress and trauma and harms physical and mental well-being, which can trigger or worsen mental health issues and lead to complex coping mechanisms like substance use. Yet there is no guarantee that those who are referred to treatment and who may need housing will receive it in a timely manner, essentially curtailing their chances of completing the program and increasing their likelihood of facing incarceration for up to three years.

Moreover, coerced treatment is antithetical to successful “Housing First” principles, which prioritize permanent housing before addressing treatment and other comprehensive needs. Policy experts also recommend against legally compelling people to comply with treatment for opioid use disorders as an alternative to other sanctions like incarceration. While coerced treatment may help engage people with substance use challenges, it likely has minimal to no effect on treatment retention, remission, and overdose mortality. This approach effectively places individuals in vulnerable positions that can lead to long-term incarceration and an increased likelihood of homelessness under Prop. 36.

Creating Safe and Equitable Communities Requires Smart Investments, Not Harsh Penalties and Mass Incarceration

Creating safe, vibrant communities for all Californians is achievable through intentional investments that uplift opportunities and economic security. Rather than promoting this positive vision for California, Prop. 36 advances an incarceration-focused approach that:

- Fails to prioritize compassionate, evidence-based strategies that help communities thrive and instead would redirect limited state resources to ineffective, punitive, and costly policies.

- Ignores the success of previous sentencing reforms that have reduced mass incarceration while maintaining crime rates well below the peaks of the past five decades.

- Would worsen existing racial, economic, and health disparities among Californians of color, who are already disproportionately represented in the carceral system.

Instead of increasing incarceration, state leaders should prioritize policies and interventions proven to reduce crime, enhance public safety, and expand behavioral health treatment options. Effective measures include increasing affordable and supportive housing, expanding economic security programs, broadening access to health care and behavioral health services, supporting education and youth intervention programs, improving recidivism reduction strategies, and implementing equity-centered policies that target vulnerable residents. By focusing on these proven strategies, we can create safer, more equitable communities for all Californians.