Introduction

On January 8, Governor Gavin Newsom released his proposed 2021-22 state budget, drawing on stronger-than-expected revenues to call for a series of emergency investments to respond to the public health and economic impacts of the pandemic and provide modest relief for Californians. These much-needed emergency investments, which the governor calls for the Legislature to enact as quickly as possible in the coming weeks, include providing $600 in one-time assistance for Californians with low incomes, extending the state’s eviction moratorium, putting steps in place to reopen schools, and providing small business assistance through loans and tax credits.

While the administration’s proposals seek to address the challenges confronting many Californians amid the pandemic, the proposed spending plan misses opportunities to address other urgent and ongoing basic needs of Californians, particularly Californians with low incomes and people of color, and particularly where investments would help to allay the health and financial strains that millions of Californians will face in the months and years to come. Notable missed opportunities include:

- Providing no new or ongoing funding for local public health departments to ensure that they have the resources they need to respond to COVID-19 and other threats to population health.

- Failing to extend comprehensive health coverage to undocumented seniors with low incomes, who are at high risk of severe illness and death from COVID-19.

- Limiting investments in a child care system that was inadequately funded before the pandemic and now confronts a crisis in the loss of providers and facilities, such that the ability of many Californians, particularly people of color, to return to the workforce will be constrained by their lack of access to affordable and quality child care.

- Failing to provide ongoing funding to prevent and combat homelessness at scale beyond the one-time support included in the governor’s proposal.

In addition, the proposed budget notably fails to recognize that the state’s unexpectedly strong fiscal health results from dramatic and widening economic inequality, where the wealthiest individuals and corporations are thriving while Californians with low and middle incomes, and particularly Black and brown Californians and other people of color, are struggling more than ever to make ends meet. California’s substantial, but concentrated, wealth means that our state can afford to make the investments needed for a more equitable recovery. State policymakers have an opportunity to put a budget plan in place that, with additional revenue and appropriate borrowing and reserves, invests in the immediate and future health and economic security of all Californians, makes the state’s tax system more equitable, and in so doing, positions our state to more quickly and equitably emerge from the recession and pandemic.

While state leaders may be inclined to rely upon stronger-than-expected revenues and the uncertain prospect of federal resources, they must recognize the need to take bolder action to provide greater state support to Californians, local governments, and communities across our state hardest hit by the pandemic.

This report outlines key pieces of the 2021-22 budget proposal, with consideration for how the plan supports — or does not meet the needs of — Californians with low incomes, as well as women, Black Californians, Latinx Californians, American Indians, Pacific Islander Californians, Asian Californians, and other Californians of color.

Contents

Budget Overview

Health

Homelessness & Housing

Economic Security

Education

Justice System

Other Proposals

Budget Overview

Governor’s Economic Outlook Is Bleak, Especially for Workers in Low-Paying Industries

California and the United States remain deep into the worst recession in generations and the financial situation for many people has worsened as the nation recently began to lose jobs again due to spiking COVID-19 cases. Job losses throughout the recession have been concentrated in industries that pay low wages and have hit Asian, Black, and Latinx workers, as well as women, particularly hard.

The governor’s economic outlook expects Californians to gain back jobs slowly, with the total number of jobs in the state not returning to pre-pandemic levels until 2025. The forecast also expects that increased automation and the shift to online retail will permanently eliminate some jobs in the low-paying leisure and hospitality, retail, and “other services” industries. This means that some unemployed workers will not have jobs to come back to once the pandemic is over and will have to find employment elsewhere. For this reason, the administration projects that employment in these industries will remain below their pre-pandemic levels beyond 2025. The outlook also points out that the recent approval of Proposition 22, which allowed gig economy companies to classify their workers as independent contractors, will lead to a decline in the quality of many jobs in the state.

It is important to consider that the governor’s outlook may be overly pessimistic because it did not take into account the impact of the federal economic relief bill that was enacted in December. This means, for example, that it incorrectly assumed that millions of Californians would lose access to unemployment benefits beginning late last year. That said, the administration points to a number of factors that could cause the economic outlook to worsen, including more widespread job losses than anticipated, more business closures than expected, or a “failure to address structural inequality.”

Governor’s Proposal Assumes Higher Revenues than Anticipated and a One-Time Windfall, but Deficits Ahead

The 2020-21 budget agreement enacted in June included actions to close a $54 billion budget gap that was projected as a result of expected revenue losses and spending increases due to the COVID-19 pandemic and recession. However, the governor’s 2021-22 budget proposal reflects an improved revenue outlook over the 2020 Budget Act assumptions and a one-time $15 billion “windfall” that can be allocated during the current budget cycle. The administration’s estimate of the windfall is significantly lower than the Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO) November estimate of $26 billion, although the LAO estimated that the actual windfall could range from $12 billion to $40 billion, depending on economic conditions.

This improved outlook and windfall are due to two main factors. First, while many Californians are facing severe struggles in the COVID-19 economy, those with high incomes have continued to fare well, and this group is responsible for a large share of the state’s General Fund revenue due to the progressive personal income tax (PIT) system. Second, the recession has been less severe than expected, largely due to federal assistance to workers, families, and businesses. As a result, the administration projects General Fund revenue will be $71 billion higher than anticipated in the 2020 Budget Act over the three-year budget period, covering fiscal years 2019-20 through 2021-22. This includes higher estimates over the budget period for the three primary General Fund revenue sources, including $58 billion in personal income tax revenue, $9 billion in sales tax revenue, and $1.3 billion in corporation tax revenue.

The budget proposal warns that the revenue situation could deteriorate in the case of a sharp decline in the stock market, a rise in bankruptcy, or more widespread unemployment affecting higher-income Californians. The proposal also notes that the revenue estimates were completed prior to the enactment of the recent federal COVID-19 relief package, which should reduce the likelihood of a more severe recession scenario in the short-term.

Although the outlook for the current budget is improved, the administration conservatively projects that the three main General Fund revenue sources will grow by only 1.9% annually between 2019-20 and 2024-25, significantly slower than the 6.4% average growth rate since 2009-10. Additionally, expenditures are expected to grow faster than revenues over this time, resulting in a structural deficit of $7.6 billion for 2022-23, growing to $11 billion by 2024-25 without actions to increase revenues, reduce spending, or a combination of the two.

Stronger-Than-Expected Revenues Allow State to Build Reserves to $22 Billion

California has a number of state reserve accounts, some of which are established in the state’s Constitution to require deposits and restrict withdrawals, and some of which are at the discretion of state policymakers.

California voters approved Proposition 2 in November 2014, amending the California Constitution to revise the rules for the state’s Budget Stabilization Account (BSA), commonly referred to as the rainy day fund. Prop. 2 requires an annual set-aside equal to 1.5% of estimated General Fund revenues. An additional set-aside is required when capital gains revenues in a given year exceed 8% of General Fund tax revenues. For 15 years — from 2015-16 to 2029-30 — half of these funds must be deposited into the rainy day fund and the other is to be used to reduce certain state liabilities (also known as “budgetary debt”). Prop. 2 also established a new state budget reserve for K-12 schools and community colleges called the Public School System Stabilization Account (PSSSA). The PSSSA requires that when certain conditions are met, the state must deposit a portion of General Fund revenues into this reserve as part of California’s Proposition 98 funding guarantee (see section on Proposition 98).

The BSA is not California’s only reserve fund. Each year, the state deposits additional funds into a “Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties” (SFEU). Additionally, the 2018-19 budget agreement created the Safety Net Reserve Fund, which holds funds that can be used to maintain benefits and services for CalWORKs and Medi-Cal participants in the event of an economic downturn.

The enacted 2020-21 budget projected drawing down $8.8 billion in reserves — $7.8 billion of $16.1 billion in available funds from the BSA; all of approximately $500 million in the PSSSA; and $450 million of the available $900 million in the Safety Net Reserve — based on projections of declining revenues due to the pandemic. The enacted budget also projected that $2.6 billion would remain in the SFEU as of June 30, 2021.

However, stronger-than-expected revenue collections result in changes to the BSA, PSSSA, and SFEU balances for the prior fiscal year (2019-20), the current fiscal year (2020-21), and projections in the governor’s proposed 2021-22 budget. The proposed budget estimates a total BSA balance of $12.5 billion in 2020-21, growing to $15.6 billion in 2021-22, and a PSSSA balance of $747 million in 2020-21, growing to $3 billion in 2021-22. The SFEU balance is estimated to be $9 billion as of June 30, 2021, declining to $2.9 billion as of June 30, 2022. In addition, the proposed budget maintains the Safety Net Reserve at $450 million.

Taking into account the BSA, PSSSA, Safety Net Reserve, and SFEU, the governor’s proposal would build state reserves to a total of $22 billion in 2021-22.

Budget Proposal Continues to Pay Down Unfunded Liabilities

The governor’s budget proposal includes required contributions to two state-run retirement systems: the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) and the California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS). CalPERS and CalSTRS, like many retirement systems, are not funded at levels that will keep up with future benefits guaranteed to workers, resulting in the state needing to make higher annual contributions in order to pay down unfunded liabilities. In recent budget agreements, state leaders have also agreed to make supplemental payments to the two systems in order to help pay down those unfunded liabilities.

The governor’s proposed budget includes the required contributions to CalPERS ($5.5 billion total, $3.0 billion General Fund) and CalSTRS ($3.9 billion General Fund). In addition, the administration proposes to make one-time supplemental payments in 2021-22 to CalPERS ($1.5 billion) and CalSTRS ($410 million) using funding set aside by Prop. 2 for paying down budgetary debt. If Prop. 2 revenues for paying down budgetary debt are available in future years, the administration projects that the state will be able to make additional supplemental payments of $4.1 billion to CalPERS and $602 million to CalSTRS over the 2022-23 to 2024-25 fiscal years. (See Reserves section for more on Prop. 2.)

Health

Proposed Budget Provides Funds for COVID-19 Public Health Emergency, But Does Not Include New Investments for Local Public Health Departments

As the state approaches almost one year into the pandemic, over 2.8 million Californians have tested positive for COVID-19 and over 31,000 Californians have died due to COVID-19 — a devastating and immeasurable loss for families and communities across the state. Communities of color, particularly Black, Latinx, and Pacific Islander Californians, have been disproportionately impacted due to long standing inequities. Since the start of the pandemic, the administration has taken steps to mitigate the spread of the virus and protect the health of Californians. Efforts include issuing stay-at-home orders, ramping up testing for the virus, securing personal protective equipment, increasing hospital capacity, and implementing a health equity metric that requires counties to address COVID-19 health inequities in their economic reopening plans.

The proposed budget continues efforts to overcome the pandemic. Specifically, the budget includes:

- Over $820 million General Fund to continue COVID-19 response measures such as laboratory capacity and testing, surveillance, response, and prevention. This builds on previous emergency and federal funding that was processed as of late fall 2020.

- About $300 million for vaccine distribution, including a public awareness campaign to increase vaccine distribution. The administration anticipates receiving an additional $350 million in federal funds for this effort. The budget summary does not state whether or not federal funds will supplement or supplant the $300 million in state funds for vaccine distribution.

While the budget consists of much-needed COVID-19-related support, no new funding for local public health departments is included. Public health officials throughout the state have expressed that more support is needed to adequately bolster public health infrastructure. Ensuring that local public health departments have the resources needed to combat COVID-19 and other threats to population health is vital. California and federal leaders must work together to provide additional resources and coordination needed to help communities adequately respond to the virus and to prepare for future threats.

Proposed Budget Fails to Expand Medi-Cal Coverage to Undocumented Seniors, Delays Potential Suspension of State Funding for Medi-Cal Provider Payments

Building on the federal Affordable Care Act (ACA), California has substantially expanded access to health coverage in recent years. For example, more than 13 million Californians with modest incomes — half of whom are Latinx — receive free or low-cost health care through Medi-Cal (California’s Medicaid program), several million more than before the ACA took effect. In addition, over 1.3 million Californians with incomes up to 600% of the federal poverty line ($76,560 for an individual) receive federal subsidies, state subsidies, or both in order to reduce the cost of coverage purchased through Covered California, our state’s health insurance marketplace. Despite these gains, millions of people — including undocumented immigrants — remain uninsured, health care costs continue to rise, and many Californians continue to face high monthly premiums and excessive out-of-pocket costs — such as copays and deductibles — when they use health care services.

The proposed budget:

- Fails to propose an expansion of comprehensive Medi-Cal coverage to seniors regardless of immigration status — even in the midst of a deadly pandemic that is disproportionately affecting older adults. In recent years, California has extended full-scope Medi-Cal coverage to undocumented immigrants under age 26 who otherwise qualify for the program. One year ago, Governor Newsom proposed to expand this state policy to include undocumented adults age 65 or older, but he withdrew this proposal in May and continues to exclude it from his 2021-22 spending plan. As a result, under the governor’s proposed budget, seniors who are undocumented would remain locked out of full-scope Medi-Cal coverage a time when preventive health services and treatment for chronic health conditions are needed most, particularly given that older adults are most at risk of severe illness from COVID-19 and even death. By failing to expand Medi-Cal to undocumented seniors, the governor misses an opportunity provide these older adults with an affordable, regular source of care, which could help to improve their health status as well as their chances of recovering from COVID-19.

- Delays, to 2022, the potential suspension of state funding for a wide array of programs and services that boost access to care and generally support Californians’ health and well-being, including certain Medi-Cal provider payments. The state budget for the current fiscal year made more than $1 billion in state spending subject to suspension in the 2021-22 fiscal year if certain conditions are met. These suspensions would take effect on either July 1, 2021, or December 31, 2021, depending on the program. The largest item on the list: supplemental payments for providers in the Medi-Cal program. This suspension would reduce state General Fund spending on Medi-Cal by nearly $760 million in 2021-22, but could impede Medi-Cal beneficiaries’ access to services if some providers stopped accepting Medi-Cal patients due to the payment cut. However, the governor proposes to prevent any health and human services suspensions from taking effect in 2021-22 by shifting the effective dates forward by one year — to July 1, 2022, and December 31, 2022.

- Projects that average monthly enrollment in Medi-Cal will increase from 14 million in 2020-21 to 15.6 million in 2021-22 — covering nearly 40% of the state’s population. This substantial year-over-year growth is due to the devastating economic downturn and job losses triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic, which continue to cause Californians to lose access to job-based health coverage. This caseload increase is projected to increase Medi-Cal spending by $13.5 billion ($4.3 billion General Fund) in 2021-22.

- Proposes to create an “Office of Health Care Affordability.” This new office would have a wide array of functions, including boosting price transparency, developing cost targets for various sectors of the health care industry, and establishing financial penalties to enforce compliance. The governor proposes to use revenues from the Health Data and Planning Fund — $11.2 million in 2021-22, $24.5 million in 2022-23, and $27.3 million in 2023-24 and ongoing — to establish and support the activities of this new office.

- Proposes to expand and make permanent certain “telehealth” flexibilities for Medi-Cal providers. This proposal would also add “remote patient monitoring” as a new Medi-Cal benefit, effective July 1, 2021, for a total cost of $94.8 million ($34 million General Fund) in 2021-22. These changes would “expand access to preventative services and improve health outcomes,” according to the governor’s budget summary.

Proposed Budget Revives Ambitious Effort to Improve Health Outcomes Through Medi-Cal Reform

The administration launched an ambitious reform effort known as CalAIM (California Advancing and Innovating Medi-Cal) in late 2019, but postponed the initiative’s implementation due to COVID-19. Building on previous pilot programs, CalAIM aims to coordinate physical health, behavioral health, and social services in a patient-centered manner with the goal of improving health and well-being, otherwise known as the “whole person care” approach. It also aims to improve quality outcomes, reduce health disparities, reduce complexity across all delivery systems, and implement value-based initiatives and payment reform.

The main goal of this initiative is to better support millions of Californians enrolled in Medi-Cal — particularly those experiencing homelessness, children with complex medical conditions, children and youth in foster care, Californians involved with the justice system, and older adults — who often have to navigate multiple complex delivery systems to receive health-related services. As such, CalAIM positions the state to take a population health, person-centered approach to providing services, and potentially reduces health care costs.

The administration assumes that implementation of these various reforms would begin on January 1, 2022, and that $1.1 billion ($531.9 million General Fund) would be available during the initial fiscal year (2021-22) to:

- Provide enhanced care management – a collaborative approach to providing intensive and comprehensive services to individuals;

- Support “in lieu of” services, which include housing transition services, recuperative care, and respite;

- Fund infrastructure needed to expand “whole person care” programs statewide;

- Build upon existing dental initiatives, such as the Dental Transformation Initiative, which aims to expand preventive dental services for children.

Substantial reforms to the Medi-Cal program as well as the level of federal funding that will be provided must be negotiated with the federal government through the Medicaid waiver process. As such, CalAIM implementation will depend on the availability of funding and federal approval.

Governor Proposes Investments in the State’s Behavioral Health System

Behavioral health services — mental health care and/or treatment for substance use — are primarily provided by California’s 58 counties, with funding from the state and federal governments. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Californians with behavioral health conditions confronted many challenges in accessing services that are delivered by multiple complex systems. The increased stress, grief, isolation, and depression highlight the need to prepare for a possible behavioral health crisis on the horizon. Given that Californians of color have been disproportionately impacted by the pandemic, state policymakers should consider the racial equity implications in future budget and policy deliberations related to behavioral health.

The administration recognizes the toll on health and well-being that COVID-19 has taken, particularly on students, and proposes several budget proposals to support behavioral health. Specifically, the administration’s proposed budget includes:

- $750 million one-time General Fund, available over three years, for competitive grants to support acquisition and rehabilitation of properties for behavioral health treatment facilities, including community-based residential facilities. (See the Homelessness and Housing section for additional information.)

- $400 million one-time in a mix of state and federal funding, available over multiple years, to implement a program intended to increase the number of students receiving behavioral health services from K-12 schools. The Department of Health Care Services would implement this program through Medi-Cal managed care plans, in partnership with county behavioral health departments and schools.

- $27.1 million General Fund for a one-year delayed suspension of Medi-Cal post-partum extended eligibility, which extends the duration of Medi-Cal eligibility for postpartum care for an individual who is diagnosed with a maternal mental health condition.

- $25 million one-time from the Mental Health Services Fund to expand the Mental Health Student Services Act Partnership Grant Program, which funds partnerships between county behavioral health departments and schools.

- $25 million ongoing Proposition 98 General Fund to fund county behavioral health partnerships that support student mental health services.

Homelessness & Housing

Governor Proposes Addressing Homelessness Through One-Time Spending to Acquire Housing Units and Residential Facilities

California has more than 25% of the nation’s population of homeless individuals, with approximately 150,000 homeless residents on a given night as of January 2019. Black Californians bear a disproportionate burden of homelessness, making up nearly 1 in 3 residents experiencing homelessness but only 6% of the overall state population. During the COVID-19 pandemic, individuals experiencing homelessness face increased risk of exposure to the virus and significant barriers to following public health guidelines to protect their health and prevent the virus from spreading.

The governor’s budget proposal highlights investments the state has made to date with state and federal dollars to address shelter needs during the pandemic. In 2021-22, the governor proposes substantial one-time spending to “further develop a broader portfolio of housing needed to end homelessness” by acquiring and rehabilitating hotels/motels and residential facilities. Specifically, the budget proposal includes:

- $750 million one-time General Fund (with $250 million available through early action before June) to continue property acquisitions through the Homekey program. Funds would continue to be administered by the Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) as competitive grants for local jurisdictions to acquire and rehabilitate hotels, motels, and other buildings and to convert them into interim or permanent housing for individuals experiencing homelessness.

- $750 million one-time General Fund, available over three years, to support the acquisition and rehabilitation of properties for behavioral health treatment facilities, including community-based residential facilities. Funds would be administered by the Department of Health Care Services as competitive grants to counties, with a local match required, producing an estimated minimum of 5,000 beds, units, or rooms. The Administration also proposes to explore redirecting $202 million in relinquished adult jail bond financing to support the purchase or modification of short-term residential mental health facilities.

- $250 million one-time General Fund for the acquisition or rehabilitation of Adult Residential Facilities (ARF) and Residential Care Facilities for the Elderly (RCFE), specifically to secure housing for low-income seniors. These facilities would provide housing, personal care, and supervision (including medication management) for individuals who are unable to live by themselves but do not need 24-hour nursing care. Funds would be available to counties through the Department of Social Services.

Additional new investments to prevent and address homelessness include one-time funds to address student hunger and homelessness at California Community Colleges and the California State University (see Community Colleges and California State University and University of California sections). The governor also points to the CalAIM proposal to transform Medi-Cal in order to better meet the needs of individuals with complex and high needs, such as individuals experiencing homelessness, through strategies that include addressing social determinants of health, including meeting housing needs (see CalAIM section).

The governor’s budget proposal does not include substantial ongoing state funding specifically to address homelessness, though advocates and legislators have identified ongoing funding at scale as a priority to successfully address California’s homelessness crisis.

Governor Proposes Extending Eviction Moratorium, Investing in Housing Development to Stimulate Economy

Even before the COVID-19 recession, more than half of California’s renter households had unaffordable housing costs. Since the start of the pandemic, millions of Californians have lost jobs, with employment losses concentrated among lower-wage workers, who are least likely to have savings to cover housing costs in the face of lost income. As of December 2020, more than 6 in 10 California adults reported having difficulty paying for usual household expenses, like rent.

To address the urgent needs of renters during the pandemic, Governor Newsom proposes immediate action to extend the state eviction moratorium beyond its current expiration date of January 31, 2021. The governor notes that the federal COVID-19 relief bill enacted in December makes approximately $2.6 billion in assistance available for rent (including back rent) and utility expenses for California renters with low incomes.

The governor’s budget proposal also includes two major one-time investments to support housing development:

- $500 million one-time General Fund for the Infill Infrastructure Grant Program (with $250 million proposed for early action before June). This investment is intended to stimulate economic recovery and job creation while facilitating housing development in infill locations.

- $500 million for expansion of the state’s Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program, which supports affordable housing development. This proposal would maintain LIHTC tax expenditures for the third year in a row at the boosted level first adopted in the 2019-20 budget.

The governor also proposes continuing to streamline the state’s housing funding programs, with $2.7 million General Fund allocated to the Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) to support this effort, while also working to improve alignment across the state’s housing finance programs. In addition, the governor proposes creating a new Housing Accountability Unit within HCD to increase the state’s focus on supporting local jurisdictions and holding them accountable for meeting their housing planning goals, with $4.3 million General Fund proposed to support technical assistance and proactive engagement provided through this new unit.

Economic Security

Governor Proposes $600 Tax Refunds for Californians With Low Incomes Through the CalEITC

Millions of Californians are continuing to struggle to pay for basic expenses like food and rent amid the worst recession in generations. Asian, Black, and Latinx workers, women, and workers paid low wages were far more likely to lose their jobs and earnings this past year, and their financial situation has likely deteriorated recently as the nation began to lose jobs once again due to spiking COVID cases.

To help address the financial challenges facing families and individuals with the lowest incomes, the governor proposes providing one-time $600 tax refunds to tax filers who qualify for California’s Earned Income Tax Credit (CalEITC) — a refundable state tax credit available to families and individuals who earn less than $30,000 per year from work. Specifically, the administration’s “Golden State Stimulus” would provide $600 to the 3.8 million tax filers who received the CalEITC last year when they filed their taxes for tax year 2019. In addition, the state would provide $600 refunds to an estimated 250,000 families and individuals who use Individual Taxpayer Identification Numbers (ITINs) to file their taxes this year for tax year 2020 and qualify for the CalEITC. These tax filers became newly eligible for the CalEITC as part of the 2020-21 budget agreement. Families and individuals who qualify for the CalEITC in tax year 2020, but who did not qualify for the credit tax year 2019 (with the exception of ITIN filers) will not be eligible to receive these payments. The administration estimates that the $600 cash payments will cost $2.4 billion.

This proposal is part of the governor’s early action in January. If this proposal is approved within the administration’s anticipated timeframe, the governor envisions that the $600 payments would begin to be sent to CalEITC recipients as early as February 2021. Californians who file their taxes with Social Security Numbers, who make up the vast majority of those qualifying for these payments, will not have to do anything to receive the cash. The Franchise Tax Board (FTB) will automatically deposit the payments into these tax filers’ bank accounts based on the information they provided on their 2019 tax returns. For filers where this information wasn’t provided or is no longer accurate, the FTB will send filers checks. Californians who file their taxes using ITINs, on the other hand, will need to file their 2020 taxes in order to receive the cash payment.

Administration Includes Some Support for Undocumented Immigrants, But Misses An Opportunity to Extend Medi-Cal to Undocumented Seniors

California has the largest share of immigrant residents of any state and is home to an estimated 2 million to 3.1 million individuals who are undocumented. Half of all California workers are immigrants or children of immigrants. About 1 in 4 of these immigrant workers is employed in an industry highly affected by the COVID-19 economic shutdown. Among California’s undocumented workers, approximately 1 in 3 are employed in an industry highly affected by the COVID-19 economic shutdown, according to Budget Center estimates. Undocumented immigrants and their families face an especially high risk of financial crisis if they lose work due to COVID-19 because they are excluded from most support programs, including standard unemployment insurance as well as expanded COVID-19 federal relief.

Prioritizing the urgent needs of undocumented immigrants and their families is an important opportunity for California’s policymakers to make our support systems more equitably inclusive, to make our state’s economy more resilient, and to lead in this time of crisis. The administration makes important strides to support Californians who are undocumented and have not recieved much if any support during the COVID-19 pandemic, but misses a key opportunity to improve health equity and make strides toward universal coverage during public health crises.

Supports in the administration’s proposal include:

- $600 tax refunds for Californians with low incomes through the CalEITC, including immigrants who use Individual Taxpayer Identification Numbers (ITINs) to file taxes. The administration’s “Golden State Stimulus” would provide $600 refunds to an estimated 250,000 families and individuals who use Individual Taxpayer Identification Numbers (ITINs) to file their taxes this year for tax year 2020 and qualify for the CalEITC. These tax filers became newly eligible for the CalEITC as part of the 2020-21 budget agreement. The governor envisions that the $600 payments would begin to be sent to CalEITC recipients as early as February 2021.

- Ongoing annual funding for immigration services. The budget proposal includes $75 million in ongoing General Fund for the unaccompanied undocumented minors and Immigration Services Funding programs. The Department of Social Services allocates funds through these two programs to nonprofit organizations who provide immigration services.

- $11.4 million one-time for the California Food Assistance Program (CFAP) emergency allotments. CFAP provides state-funded food assistance to “qualified” immigrants who are not eligible for CalFresh, California’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Under the governor’s proposal, the state would provide $11.4 million General Fund to maintain CFAP emergency allotments from July through December 2021, with these state funds offset by federal Coronavirus Relief Funds. These emergency allotments increase households’ food assistance benefits to the maximum benefit for their household size. However, the additional funding does not reflect a 15% increase in the maximum benefit as was approved for SNAP households in the recent federal economic relief bill. State policymakers should ensure that this 15% increase is also reflected for CFAP households, keeping with the longstanding practice of aligning CFAP benefits with CalFresh. In addition, state policymakers should consider expanding eligibility for CFAP to meet the needs of California’s immigrant population. The most recent available data from October 2020 shows that over 35,000 people participated in CFAP. Participation peaked in June, when nearly 40,000 people benefited from CFAP.

- $5 million one-time General Fund for Rapid Response Program. This additional funding is to provide support to entities that provide critical assistance and services to immigrants during emergent situations.

- New requirement that all eligible high school seniors complete a California Dream Act Application. Local educational agencies would be required to ensure compliance beginning in the 2021-22 academic year. The California Student Aid Commission reported a 45% decrease in California Dream Act application completions in 2020 compared to 2019.

Missed opportunities in the administration’s proposal include:

- Failure to expand comprehensive Medi-Cal coverage to seniors regardless of immigration status — even in the midst of a deadly pandemic that is disproportionately affecting older adults. In recent years, California has extended full-scope Medi-Cal coverage to undocumented immigrants under age 26 who otherwise qualify for the program. One year ago, Governor Newsom proposed to expand this state policy to include undocumented adults age 65 or older, but withdrew this proposal in May and continues to exclude it from his 2021-22 spending plan. As a result, under the governor’s proposed budget, seniors who are undocumented would remain locked out of full-scope Medi-Cal coverage at a time when preventive health services and treatment for chronic health conditions are needed most, particularly given that older adults are most at risk of severe illness from COVID-19 and even death. By failing to expand Medi-Cal to undocumented seniors, the governor misses an opportunity to provide these older adults with an affordable, regular source of care, which could help to improve their health status as well as their chances of recovering from COVID-19.

- Not including new funding to expand student support services for immigrant students including undocumented students in California Community Colleges. The 2020-21 budget allocated $5.8 million for Dreamer Resource Liaisons and student support services, but no additional funding is proposed in the 2021-22 budget.

The Administration’s January Proposal Makes Modest Adjustments to the CalWORKs Program, Anticipates an Increased Caseload

The California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) program provides modest cash assistance for low-income children while helping parents overcome barriers to employment and find jobs. Even before the COVID-19 crisis, CalWORKs primarily served children of color, who faced higher rates of economic insecurity than did white children. Now, with millions of California workers who have lost their jobs or seen reduced wages due to a long-term public health emergency and recession, CalWORKs is a particularly critical source of support.

In his January proposal, the governor proposes allocating $7.4 billion in federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) funds to support the CalWORKs program in 2021-22. Part of this spending reflects the administration’s anticipation of an increase in the average monthly number of CalWORKs families, due to the economic downturn. Workers of color — especially Black and Latinx women — have experienced the largest drops in employment due to the COVID-19 recession. With the loss of millions of jobs in California, it will be harder and will take longer for parents with work barriers to secure jobs that can cover the costs of living while also keeping their families safe and healthy. More parents will need to turn to CalWORKs for support, including some parents who turned to CalWORKs for support previously during the difficult job market and loss of housing stability in the Great Recession.

Unlike most states, where parents are allowed to receive cash support for 60 months, California restricts parents in CalWORKs to only 48 months. Though this restriction, which began in 2011, was lifted in the 2020-21 budget, the restoration of the 60-month time limit will not take effect until at least May 2022 due to data system constraints. Until then, the January proposal provides $46.1 million one-time General Fund to ensure that CalWORKs clients who receive assistance during the COVID-19 pandemic can continue to do so without running down their 48-month clock.

Finally, the governor also proposes $50.1 million for a 1.5% grant increase, effective October 1, 2021. This increase would not be funded through the General Fund but instead through the Child Poverty and Family Supplemental Support subaccounts of the Local Revenue Fund.

Governor’s Proposal Offers Small Amount of Support for Subsidized Child Care, Does Not Include Plan for Federal COVID-Relief Funds

California’s subsidized child care and development system provides assistance for working parents with low and moderate incomes who are struggling to afford the cost of child care for their children. During this unprecedented health and economic crisis, many child care providers in California have stepped up to the challenge of providing early learning and care and distance learning support for families — particularly for children with parents who are essential workers. While the state and federal government have both provided emergency funding to support child care providers, total support falls far short of the estimated level necessary to sustain this critical system. Meanwhile, family budgets are even more strained due to lost jobs and wages, and without access to safe and affordable child care, many California families may not be able to return to work.

The governor’s proposed budget provides a small amount of funding to support child care providers and families. Specifically, the proposal:

- Provides $55 million one-time General Fund for child care providers and families who are struggling due to the COVID-19 health and economic crisis. Additional details are not available.

- Provides $44.3 million in Proposition 64 Cannabis Funds for roughly 4,500 spaces in the Alternative Payment Program. The governor proposes making $21.5 million available in the current fiscal year and $44 million ongoing.

- Shifts $31.7 million and 185.7 staff positions from the California Department of Education to the Department of Social Services as part of the planned migration of child care programs that was part of the 2020-21 budget agreement. Administration of and funding for child care programs operated by the California Department of Education will also shift to the Department of Social Services on July 1, 2021.

Absent from the administration’s proposal is a plan to distribute an estimated $1 billion in federal funds — California’s expected share of the $10 billion in federal Child Care and Development Block Grant funds included in the most recent COVID relief package included in the Consolidated Appropriations Act. While the 2020-21 budget agreement stipulated how up to $300 million should be allocated if the state received additional federal funds, these items are also absent from the budget document released by the administration. The state has 60 days from the enactment of the federal relief package — which occurred on December 27, 2020 — to submit a plan for the use of these dollars.

Supporting child care in California is critical to helping providers survive the COVID-19 crisis, supporting parents who have no choice but to work outside the home, and aiding the state’s economic recovery.

Proposed Budget Lacks a State Increase for SSI/SSP Grants, but Includes New State Funding for Housing, Alzheimer’s, and Other Initiatives to Assist Seniors

Supplemental Security Income/State Supplementary Payment (SSI/SSP) grants help well over 1 million low-income seniors and people with disabilities to pay for housing and other necessities. Grants are funded with both federal (SSI) and state (SSP) dollars. State policymakers made deep cuts to the SSP portion of these grants to help close budget shortfalls that emerged after the onset of the Great Recession in 2007. Since then, state policymakers have provided only one increase to the state’s SSP portion of the grant — a 2.76% boost that took effect in January 2017, resulting in monthly SSP grant levels of $160.72 for individuals and $407.14 for couples, which continue to remain in effect.

Although the recently released Master Plan for Aging recognizes that SSI/SSP grants have “not kept up with poverty levels,” the governor proposes maintaining the SSP portion at the current inadequate levels into 2022. However, the federal government is expected to increase the SSI portion of these grants by 2.2% in January 2022. This increase would boost maximum SSI/SSP grants by $17 per month for individuals (to $971.72) and by $26 per month for couples (to $1,624.14).

While the governor misses an opportunity to boost state financial assistance for older adults and people with disabilities, he does propose new investments aimed at assisting these Californians in other ways. For example, the proposed budget:

- Provides $250 million to preserve and expand housing for certain seniors with low incomes. The Department of Social Services would use this one-time funding to acquire and rehabilitate Adult Residential Facilities (ARFs) and Residential Care Facilities for the Elderly (RCFEs), with the goal of maintaining and increasing housing options for seniors who are homeless or at risk of homelessness. (This proposal is also discussed in the Homelessness section.)

- Allocates $17 million to improve the state’s approach to Alzheimer’s disease. This one-time funding would support a public education campaign on brain health ($5 million); Alzheimer’s-related research ($4 million); new training and certification for caregivers ($4 million); expanded training for health care providers ($2 million); and grants to help communities become “dementia-friendly” ($2 million). Overall, this approach would emphasize people of color and women, who are disproportionately affected by Alzheimer’s, according to the budget summary.

- Provides $7.5 million to expand one-stop information centers that serve seniors, people with disabilities, and people living with Alzheimer’s. These centers — known as Aging and Disability Resource Connections (ADRCs) — currently serve about one-third of the state and would be expanded statewide under the governor’s proposal. ADRCs provide “access to information and assistance with aging, disability, and Alzheimer’s, in multiple languages and with cultural competencies,” according to the governor’s budget summary. Funding for these centers would be subject to suspension on December 31, 2022, under the governor’s proposal.

- Includes $3 million to increase and diversify the geriatric medicine workforce. This one-time funding is intended to develop “a larger and more diverse pool of health care workers with experience in geriatric medicine,” according to the governor’s budget summary.

Proposed Budget Includes Proposals to Address Food Hardship

Food hardship has skyrocketed in California due to the COVID-19 health and economic crisis. This is particularly true for Black and Latinx Californians and other Californians of color who have been hit hard by the pandemic and are much more likely to not have enough food to eat. The governor’s proposed budget includes a number of food and nutrition proposals to help address food hardship in California. Specifically, the proposed budget:

- Provides $11.4 million one-time for the California Food Assistance Program (CFAP) emergency allotments. CFAP provides state-funded food assistance to “qualified” immigrants who are not eligible for CalFresh, California’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Under the governor’s proposal, the state would provide $11.4 million General Fund to maintain CFAP emergency allotments from July through December 2021, with these state funds offset by federal Coronavirus Relief Funds. These emergency allotments increase households’ food assistance benefits to the maximum benefit for their household size. However, the additional funding does not reflect a 15% increase in the maximum benefit as was approved for SNAP households in the recent federal economic relief bill. State policymakers should ensure that this 15% increase is also reflected for CFAP households, keeping with the longstanding practice of aligning CFAP benefits with CalFresh. In addition, state policymakers should consider expanding eligibility for CFAP to meet the needs of California’s immigrant population. (See also Immigration section.)

- Extends increased funding for the Senior Nutrition Program, providing a total of $17.5 million in 2021-22. This includes catered meals as well as the Meals on Wheels program. Funding for this program was subject to suspension on December 31, 2021, but this potential suspension was delayed by one year, to December 31, 2022.

- Provides an additional $22.3 million ongoing General Fund for the Supplemental Nutrition Benefit and Transitional Nutrition Benefit programs. As part of the 2018-19 budget agreement, state policymakers eliminated the “SSI cash-out,” allowing people enrolled in SSI/SSP to receive federal food benefits provided through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) — called CalFresh in California. As a result of this policy change, certain households that were already receiving CalFresh benefits would have experienced a reduction in those benefits or become ineligible for CalFresh. The Supplemental Nutrition Benefit and Transitional Nutrition Benefit programs were created to offer state-funded benefits to these households to ensure that they did not lose critical assistance. The proposed budget would increase the average benefit amount for each program.

- An additional $30 million one-time General Fund for food banks. Recognizing the vital role that Emergency Food Assistance Programs, food banks, tribes, and tribal organizations play in making sure Californians have enough to eat, the proposed budget includes an additional $30 million in one-time funding. Millions in California have recently turned to food pantries and food banks during the current recession, but this funding has not been identified for early action, despite the severity of the crisis. Additionally, this boost in one-time funding likely falls short of the levels necessary to adequately address the hunger crisis across the state.

- Provides $115 million to support college students’ basic needs, including access to food. The proposed budget includes $100 million one-time Proposition 98 funding to support CCC students experiencing housing and food insecurity in order to help mitigate the effects of the pandemic. The governor also proposes $15 million ongoing General Fund to address basic needs — such as hunger, homelessness, and financial insecurity — for California State University students through the Graduation Initiative 2025. (See also Community Colleges and California State University/University of California sections.)

Many in California are struggling to afford basic expenses while the COVID-19 pandemic rages unchecked. The governor’s proposed budget offers much-needed food assistance but none of these proposals are currently identified as “early action” items to be fast-tracked by state policymakers, despite the very clear need.

Education

Governor’s Proposal Invests in Transitional Kindergarten

Transitional kindergarten is the first year of a two-year kindergarten program for children who turn five on or between September 2 and December 2 of the year they enter the program. Eligibility is based on age alone in public schools and is not dependent on family income. As part of the administration’s recently released Master Plan for Early Learning and Care, the 2021-22 budget proposal invests $500 million in one-time funding to make transitional kindergarten more accessible for families. This includes:

- $250 million one-time Proposition 98 General Fund for incentive grants for school districts to expand transitional kindergarten programs to younger children born after December 2. These funds would be distributed over a multi-year period.

- $200 million one-time General Fund for school districts to construct or retrofit existing facilities in order to offer transitional kindergarten and full-day kindergarten programs. This is on top of $100 million included in the 2018-19 budget agreement for the same purpose, of which nearly all has been spent.

- $50 million one-time Prop. 98 General Fund for training for transitional kindergarten and kindergarten teachers. Training instruction is to focus on a variety of issues meant to create more inclusive classrooms, such as implicit-bias training and supporting English Language Learners.

Despite rescinding significant funding as a result of the pandemic, the governor’s proposed budget does not include funding for the California State Preschool Program — a program serving children from families with low and moderate incomes in community-based organizations and local education agencies. The State Preschool Program may be better positioned to provide services for working families with low incomes who need wraparound child care services beyond school hours and during summer months.

Increased Revenues Boost the Minimum Funding Level for Schools and Community Colleges

Approved by voters in 1988, Proposition 98 constitutionally guarantees a minimum level of annual funding for K-12 schools, community colleges, and the state preschool program. The governor’s proposed budget assumes a 2021-22 Prop. 98 guarantee of $85.8 billion for K-14 education, $14.9 billion above the 2020-21 funding level of $70.9 billion estimated in the 2020-21 budget agreement. The Prop. 98 guarantee tends to reflect changes in state General Fund revenues and estimates of 2019-20 and 2020-21 General Fund revenue in the proposed budget are higher than those in the 2020-21 budget agreement. The governor’s budget proposal assumes a 2020-21 Prop. 98 funding level of $82.8 billion, $11.9 billion above the level assumed in the 2020-21 budget agreement, and a $79.5 billion 2019-20 Prop. 98 funding level, $1.9 billion above the level assumed in the 2020-21 budget package. Last year’s budget agreement did not include a deposit into the Public School System Stabilization Account (PSSSA) – the state budget reserve for K-12 schools and community colleges – due to projections for weak revenue from capital gains and a decline in the Prop. 98 funding guarantee. Revised projections in the governor’s proposed budget, however, would require a PSSSA deposit of $747 million in 2020-21 and an additional $2.2 billion in 2021-22, bringing the PSSSA total to $3 billion.

To address the reduction in Prop. 98 funding for K-12 schools and community colleges that was projected last year, the 2020-21 budget agreement included a provision to supplement Prop. 98 funding beginning in 2021-22 by 1.5% of annual General Fund revenues. This new spending obligation was slated to continue until the total in supplemental payments reached $12.4 billion. Because of the significant increase in General Fund revenue projections in the governor’s proposed budget, his spending plan eliminates this ongoing obligation and instead includes a one-time supplemental payment of $2.3 billion for K-14 education in 2021-22.

Governor Proposes to Repay Some Deferred Funding to Schools and Provide a Large Amount of One-Time Funding to Address Pandemic-Related Educational Disruptions

The largest share of Prop. 98 funding goes to California’s school districts, charter schools, and county offices of education (COEs), which provide instruction to more than 6 million students in grades kindergarten through 12. The governor’s proposed budget repays school districts for a large amount of payments that were deferred in last year’s budget agreement, allocates significant one-time funding to address the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on students and to incentivize schools to provide in-person instruction, and increases ongoing funding for the state’s K-12 education funding formula – the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). Specifically, the governor’s proposed budget:

- Provides $7.3 billion to repay deferred payments to K-12 school districts. The 2020-21 budget agreement deferred $11.0 billion in LCFF payments for K-12 school districts until 2021-22. The payment deferrals allowed the state to authorize a level of spending by K-12 schools that the state could not afford in 2020-21, providing the state with one year of savings without requiring a reduction in K-12 education spending. While repaying a large amount of the deferrals in 2021-22, the governor’s proposed budget would continue to defer $3.7 billion in LCFF payments until 2022-23.

- Provides $4.6 billion in one-time funding for expanded learning time and academic intervention grants. To address educational disruptions due to the pandemic, the budget proposes early action before June and targets these dollars for interventions focused on English learners, students from low-income families, and foster and homeless youth, such as an extended school year or summer school.

- Allocates $2 billion in one-time funding for In-Person Instruction Grants. These per pupil grants would be available beginning in February 2021 to school districts, COEs, and classroom-based charter schools that fulfill a series of requirements that include:

- submitting a COVID-19 School Safety Plan to their COE, or the California Department of Education for single-district counties;

- providing an option for in-person instruction by no later than March 15, 2021 for transitional kindergarten through 6th grade; and

- providing the option for in-person instruction to at least students with disabilities, foster youth, homeless youth, and students who are not able to participate in online instruction.

Schools not able to provide in-person instruction due to high COVID-19 case rates in their county or local health jurisdiction would be eligible for full grant amounts if they fulfill grant requirements and the seven-day adjusted average COVID case rates in their county or local health jurisdiction falls below 28 cases per 100,000 people per day. In-Person Instruction Grants would be available for use until December 31, 2021 and could be used for any purpose consistent with providing in-person instruction such as teacher salaries, COVID-19 testing, or personal protective equipment.

- Increases LCFF funding by $2 billion. The LCFF provides school districts, charter schools, and COEs a base grant per student, adjusted to reflect the number of students at various grade levels, as well as additional grants for the costs of educating English learners, students from low-income families, and foster youth. The governor’s proposal would provide a cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) of 3.84% in 2021-22, which includes making up for last year’s budget agreement not providing a 1.5% COLA for the LCFF in 2020-21.

- Provides more than $300 million in one-time funds for educator professional development. The governor’s proposal would fund several programs including $250 million for the Educator Effectiveness Block Grant, $50 million to create statewide resources and provide professional development on social-emotional learning and trauma-informed practices, and $8.3 million for the California Early Math Initiative to provide teacher professional development in mathematics teaching strategies.

- Provides $264.9 million in one-time funds for community schools. Community schools provide integrated educational, health, and mental health services to students. The governor’s budget proposes to use community school grants for school districts to develop new and expand existing networks of community schools with priority given for schools in high-poverty communities.

- Provides $225 million in one-time funds to improve the teacher pipeline. The governor’s proposal would increase funding by $100 million for the Golden State Teacher Grant Program, a grant program for students enrolled in teacher preparation programs who commit to teach in “high-need” subjects, including bilingual education, STEM, and special education (also see Student Financial Aid section); $100 million for the Teacher Residency Program, a competitive grant program established in 2018 to recruit and prepare special education, science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and bilingual education teachers to teach in high-need communities; and $25 million for the California Classified School Employees Credentialing Program, which provides grants to K-12 school districts to recruit school employees to become classroom teachers.

- Provides $85.7 million to fund COLAs for non-LCFF programs. The governor’s proposed budget funds a 1.5% COLA for several categorical programs that remain outside of the LCFF, including special education, child nutrition, and American Indian Education Centers.

The Budget Proposal Expands Supports for Low-Income Community College Students Hardest Hit by the Effects of the Pandemic

A portion of Proposition 98 funding provides support for California Community Colleges (CCCs), the largest postsecondary education system in the country. CCCs help prepare nearly 2.1 million students to transfer to four-year institutions or to obtain training and employment skills. In 2017-18, about 126,000 CCC students transferred to a four-year postsecondary institution — approximately 32,000 of those were first-generation students — and in 2018-19, more than 84,000 students earned an associate’s degree.

The 2021-22 budget proposal includes emergency financial support for students most affected by the pandemic, invests in targeted efforts to engage and retain students, increases access and quality of remote learning, and makes investments in workforce development. Specifically, the proposed spending plan:

- Includes approximately $1.1 billion to reduce deferred payments to CCCs. To avoid spending cuts, the 2020-21 budget agreement deferred $1.5 billion in payments to CCCs until 2021-22. The budget proposal includes repayment of a portion of these deferrals, but still defers approximately $326.5 million from 2021-22 to 2022-23.

- Proposes $250 million in one-time funding to expand financial assistance for students experiencing hardship due to the pandemic. The budget proposes early action before June to provide $100 million in funding for emergency financial support for full-time, low-income students who lost full-time employment. The budget proposal also includes $150 million for this same purpose for 2021-22, after June.

- Includes an increase of $111.1 million for a 1.5% cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) for apportionments.

- Provides $100 million in one-time funding to support student basic needs. The proposed budget includes support for CCC students experiencing housing and food insecurity in order to help mitigate the effects of the pandemic.

- Includes $40.6 million in ongoing funding to bolster remote learning and support student mental health. An increase of $30 million Prop. 98 would support students’ basic technology needs and make progress in closing the digital divide by helping students acquire devices and high-speed internet and also increase student access to mental health resources. The proposed budget also includes $10.6 million to continue improving distance learning, online access to academic support, counseling, and mental health services.

- Includes $20 million in one-time funds to address a decline in student enrollment as a result of the pandemic and increase retention rates. From fall 2019 to fall 2020, student enrollment at CCCs has dropped by roughly 8%. As part of the early action package, the proposed investment would support re-enrollment, retention, and recruitment.

- Includes $20 million in one-time funding to expand work-based learning programs at CCCs. This investment would expand work-based learning programs, models, and curriculum.

- Provides $15 million in ongoing funds to expand the California Apprenticeship Initiative. The apprenticeship program supports the expansion of apprenticeship opportunities for training and development in growing and priority industries.

Absent from the administration’s proposal is additional funding to expand student support services for immigrant students, including undocumented students in CCCs. CCCs provide support through Dreamer Resource Liaisons and legal services for immigrant students, faculty, and staff. Changes in federal immigration policies have increased the need for services and greater investment is necessary to advance economic justice for immigrant students.

The January Proposal Increases Funding for the CSUs and UCs, Includes Some Additional Support to Address Equity

California supports two public four-year higher education institutions: the California State University (CSU) and the University of California (UC). The CSU provides undergraduate and graduate education to roughly 486,000 students on 23 campuses, and the UC provides undergraduate, graduate, and professional education to about 285,000 students on 10 campuses.

For the CSU, the administration proposes $144.5 million in ongoing General Fund, including:

- $111.5 million to support a three percent increase in base resources for operational costs.

- $15 million to address basic needs (such as hunger, homelessness, and financial insecurity) for students through the Graduation Initiative 2025.

- $15 million to address inequities in digital connectivity and for mental health support.

- Over $3 million for other purposes such as an online learning platform, expansion at CSU Stanislaus, Stockton, and broadband access.

The governor also proposes one-time spending of $225 million General Fund, including $30 million for emergency grants to low-income students and students working full-time. The remainder would go to support deferred maintenance, faculty development, and the Computing Talent Initiative at CSU Monterey Bay.

For the UC, the administration proposes $136 million in ongoing General Fund, including:

- $103.9 million to support a three percent increase in base resources for operational costs.

- $15 million to address inequities in digital connectivity and improve access to mental health resources.

- $12.9 million for UC Programs in Medical Education, including an expansion to focus on American Indian communities. (See also Other Proposals section.)

The governor also proposes one-time spending of $225 million General Fund, including $15 million for emergency grants for low-income students and those working full-time. The remainder would support deferred maintenance, professional development for K-12 teachers to address ethnic studies and learning loss mitigation, and other purposes.

The administration would provide these funds with the expectation that both the CSU and the UC would maintain current tuition and fee levels. Both institutions would also be expected to take action to reduce equity gaps by 2025 and to create pathways to guarantee admission to first-time freshmen who have completed an Associate Degree for Transfer from the California Community Colleges.

Administration Provides Additional Emergency Financial Assistance Grants and Funds Golden State Teacher Grant Program

Cal Grants are the foundation of California’s financial aid program for low- and middle-income students pursuing higher education in the state. Cal Grants provide aid for tuition and living expenses that do not have to be paid back. Ensuring Californians have access and the resources to attend and thrive in the state’s higher education institutions broadens opportunities for individuals and families as well as strengthens our state’s workforce to drive long-term economic growth. Many students already confront significant hardships to afford tuition and living expenses, including student-parents, current and former foster youth, undocumented students, and those from families with low incomes. These students now face added layers of stress and financial insecurity due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In order to address these challenges and continue to support California’s higher education students, the proposed 2021-22 budget includes:

- $295 million one-time General Fund for emergency student financial assistance grants. This includes $250 million for California’s Community Colleges, $30 million for the California State University, and $15 million for the University of California. The additional student grants will target full-time, low-income students who were previously working full-time and who demonstrate a financial need. The governor proposes $100 million for California’s Community Colleges to be included in an early action package this spring.

- $100 million one-time General Fund for the Golden State Teacher Grant Program. The program is intended to provide grants of $20,000 for teachers committed to teaching for four years in “high-need” subjects — including bilingual education, STEM, and special education — and in schools that have a high percentage of teachers with “emergency-type permits.”

- $35 million ongoing General Fund to add 9,000 Competitive Cal Grant awards. Competitive Cal Grants support students who attend college more than a year after high school graduation and meet certain income and GPA requirements. The additional funding will expand the number of available grants to 50,000, up from the current level of 41,000.

- $20 million ongoing General Fund for former and current foster youth access award. Eligible new or renewal Cal Grant A and B students will receive awards up to $6,000 and Cal Grant C students will receive $4,000.

- A new requirement that all high school seniors complete a FAFSA or California Dream Act Application. Local education agencies would be required to ensure compliance beginning in the 2021-22 academic year. The California Student Aid Commission reported that there was a 10% decrease in FAFSA and 45% decrease in California Dream Act application completions in 2020 compared to 2019.

Justice System

Proposed Budget Reports That California Is on Track to Spend More Than $1 Billion Related to COVID-19 in State Prisons, as the Virus Continues to Spread

More than 95,400 adults who have been convicted of a felony offense are serving their sentences at the state level, down from a peak of 173,600 in 2007. More than two-thirds of state prisoners are Black or Latinx individuals — a racial disparity that reflects implicit bias in the justice system, structural disadvantages faced by these communities, and other factors. Among all incarcerated adults, most — 90,639 — are housed in state prisons designed to hold fewer than 85,100 people. This level of overcrowding is equal to 106.5% of the prison system’s “design capacity,” which is below the prison population cap — 137.5% of design capacity — established by a 2009 federal court order. (In other words, although state prisons remain overcrowded, the state is complying with the court order.) In addition, California houses over 4,800 people in facilities that are not subject to the court-ordered cap, including fire camps, in-state “contract beds,” and community-based facilities that provide rehabilitative services. The sizable drop in incarceration has resulted both from 1) a series of reforms to the justice system enacted during the 2010s and 2) changes adopted in 2020 to further reduce prison overcrowding in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, such as suspending intakes from county jails and implementing early releases.

The proposed budget:

- Projects the state is on track to spend $1.1 billion on COVID-19 activities in state prisons from the onset of the pandemic to the end of the current fiscal year (June 30, 2021). Moreover, the governor proposes to spend an additional $281.3 million on COVID-19 activities in prison during the upcoming 2021-22 fiscal year.

- Confirms that COVID-19 continues to spread among incarcerated adults and prison staff. In December 2020, active cases among incarcerated adults exceeded 9,000, and active cases among staff surpassed 2,600, with every state prison having had active cases at some point. Furthermore, 103 incarcerated adults at 17 prisons had died of COVID-19 as of mid-December.

- Reports that the number of adults incarcerated at the state level is substantially lower than expected largely due to state actions taken in response to COVID-19. The state projected an average daily prison population of 122,536 when the 2020-21 budget was adopted last June. The governor now estimates an average daily population of 97,950 in 2020-21 — 20% below the original estimate. Moreover, the state projects the prison population will drop by an additional 2,626 between 2020-21 and 2021-22. These significant declines are largely due to actions the state has taken to reduce overcrowding and mitigate the spread of the virus among incarcerated adults. These actions include suspending intakes from county jails and implementing early releases.

- Continues to plan for the closure of two state prisons over the next couple of years. The administration plans to close the Deuel Vocational Institution by September 2021, for General Fund savings of $113.5 million in 2021-22, rising to $150.6 million in 2022-23. A second state-operated prison is planned for closure in 2022-23, although the specific institution that will be closed has not been announced.

- Includes $23.2 million in 2020-21 for technology needed to increase incarcerated adults’ access to remote-learning opportunities. This proposal includes the purchase of about 38,000 laptop computers for adults enrolled in community college courses and other academic programs. It also includes the expansion of network bandwidth and the creation of a “secure online academic portal” that would allow students to complete their educational programs remotely. Maintaining these initiatives would cost $18 million per year beginning in 2022-23, according to the governor’s budget summary.

Proposed Budget Increases Funding for County Probation Departments and Continues Fines and Fees Assistance for Californians With Low Incomes

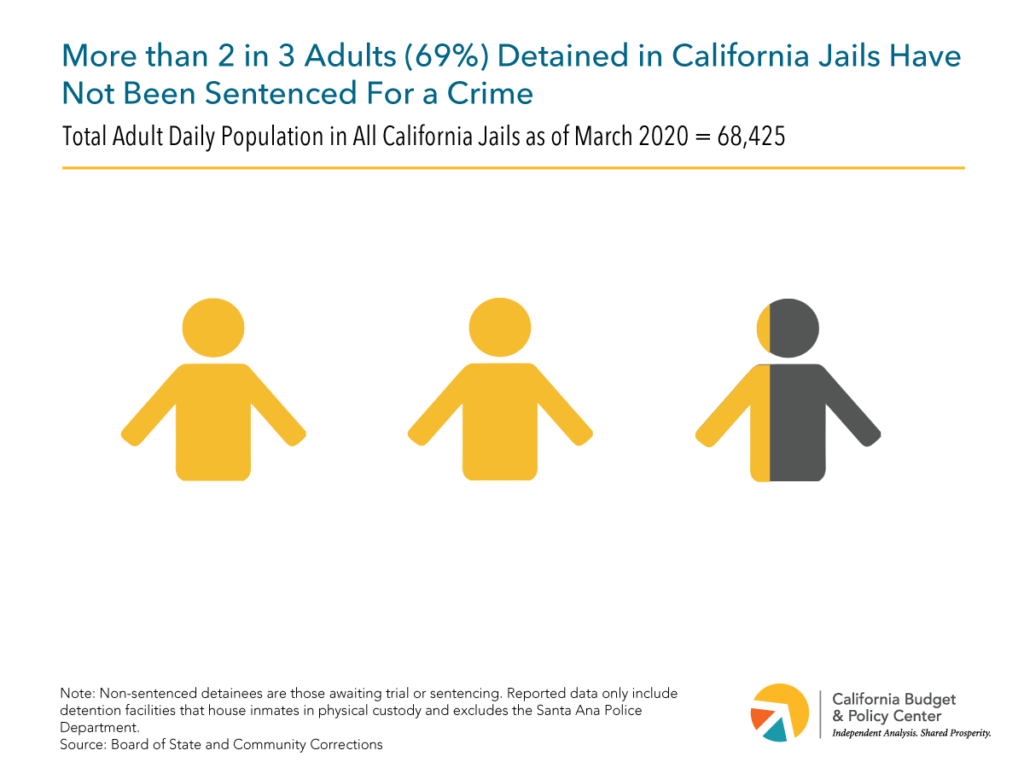

All California counties play a key role in the state’s local correctional system, including by operating jails and supervising adults and juveniles on probation. While COVID-19 health concerns pushed most counties to continue temporarily lower bail schedules and reduce the number of people held in custody, county jails still house roughly 58,000 adults on a given day. Counties’ role in corrections was transformed by the state-to-county “realignment” that took effect in 2011, following a US Supreme Court order that required the state to reduce its prison population. Under realignment, counties are responsible for managing certain adults who had traditionally been housed in state prisons and supervised by state parole officers upon their release. Recently, juvenile justice realignment also transferred responsibility for youth who are wards of the state to counties. As of June 30, 2021, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation Division of Juvenile Justice (DJJ) will no longer house juveniles, with limited exceptions, and transfer care for these youths to counties.

In this budget, the administration acknowledged the increasing responsibility counties are undertaking due to their key role in rehabilitation and adult and juvenile realignment. To this end, the proposed budget provides:

- $122.9 million ongoing General Fund to county probation departments to support efforts to maintain or reduce current probation revocation rates due to COVID-19 changes to statewide probation policy.

- $50 million one-time General Fund in 2020-21 for county probation departments to enhance a broad range of services to quickly and effectively prevent youth and adults from entering or reentering the criminal justice system. The governor proposes early legislative action for this funding in 2021.

- $46.5 million General Fund in 2021-22, $122.9 million in 2022-2023, $195.9 million in 2023-24, and $212.7 million in ongoing in 2024-25 for county probation departments to take responsibility for youth who will be under their jurisdiction once the DJJ closes.

- $19.5 million one-time General Fund in 2021-22 for county probation departments for additional adults on Post-Release Community Supervision due to a temporary increase in the daily population.

The local correctional system is also accompanied by California’s 58 county-based trial courts that supplement the foundation of the state’s judicial branch – ruling on both civil and criminal cases. The governor’s proposal continues ongoing efforts to reduce criminal fines and fees for Californians with low incomes through allocating $12.3 million General Fund in 2021-22, increasing to $58.4 million ongoing General Fund by 2024-25. These proposed funds are allocated to expand a pilot program currently administered by the Judicial Council in six courts to county courts statewide. This would allow Californians with qualifying incomes to reduce their penalties by 50% or more and make payments over time for certain traffic and non-traffic related fines and fees.

Other Proposals

Proposed Budget Includes New Investments in Job Creation, Small Business Relief, and Workforce Development

The governor’s budget contains a series of proposals intended to create and retain jobs, assist small businesses struggling due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and provide training and industry linkages for those entering or re-entering the workforce.

The governor proposes $777.5 million for a “California Jobs” Initiative, which includes: