Introduction

On March 12, President Biden signed the American Rescue Plan (ARP) Act to provide much needed assistance to tens of millions of people, including millions of Californians. The $1.9 trillion federal aid package will bring approximately $150 billion in federal aid to California to help reduce economic hardship for low- and middle-income households, support workers, help schools address learning needs, boost early care and learning, combat housing instability and homelessness, and bolster the economy.

This latest round of federal fiscal relief will help reduce hardship as a result of the pandemic, particularly for Californians with low incomes and people of color, and begins to set the stage for a more equitable economic recovery. This report outlines key provisions of the plan and what it means for Californians.

Contents

Fiscal Aid to State and Local Governments

Recovery Rebates & Tax Credits

Supports for Workers

Economic Security

Health

Housing and Homelessness

Education

Fiscal Aid to State and Local Governments

American Rescue Plan Provides Direct Aid to State and Local Governments

How much funding is available and how much will California receive?

Federal lawmakers authorized $350 billion in flexible fiscal aid to state and local governments.

How can the funding be used?

The federal fiscal aid can be used for any of the following purposes.

- Covering COVID-19-related public health and economic costs.

- Offsetting state and local government revenue losses compared to the prior fiscal year.

- Providing premium pay to essential workers of up to $13/hour on top of their current wages, up to a maximum of $25,000 per worker.

- Expanding broadband, water, and sewer infrastructure.

Any government adopting tax cuts that result in a net loss of revenue will lose an equivalent amount in federal aid. While this restriction is intended to ensure that state and local governments are spending the fiscal aid on COVID-19 relief and related purposes, it may also apply to tax credits that provide cash assistance to low-income households and small businesses harmed by the pandemic. The US Treasury is expected to provide clarification on the use of those credits by mid-May.

States and local governments are also prohibited from using the fiscal aid to make deposits into state and local pension funds.

How soon will the funding arrive and what is the timeline for using it?

The US Treasury will distribute funding to states by mid-May. Counties and cities will receive 50% of their allocations by mid-May and the other 50% a year later. There is no deadline for spending the funds.

What does this mean for California?

The significant and flexible fiscal aid provided by the federal government means that California’s state and local governments will have additional funding to address the public health and economic effects of the pandemic over the next couple of years and provides fiscal stability, particularly to local governments confronting declining revenues as a result of business closures and reduced retail and tourism activity. The fiscal aid also helps California’s state and local governments avoid having to cut vital public support for Californians, particularly low-income households and people of color who have been disproportionately harmed by the pandemic.

Recovery Rebates

Third Rebate Provides Cash to Many Households, but Some Californians Remain Excluded

How do the rebates work and who will benefit?

The American Rescue Plan provides a third recovery rebate to most US households equal to $1,400 per family member – the largest recovery rebate to date. To qualify for the full rebate, married-joint tax filers must have incomes of $150,000 or less, heads of household must have incomes of $112,500 or less, and all other filers must have incomes of $75,000 or less. Filers with incomes slightly above these limits qualify for a portion of the rebate.

When will Californians benefit from the rebates?

Most people who are eligible for the third recovery rebate will receive the payment automatically from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), which began sending payments soon after the ARP was signed into law.

How much money could Californians receive?

Californians could receive $35 billion to $43 billion in total from these rebates, according to estimates by the Legislative Analyst’s Office and the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. These estimates imply that between 25 million and 31 million Californians could receive these payments.

What does this mean for Californians?

Most Californians will receive the third federal rebate, and those with low incomes will have an easier time paying for basic expenses. Undocumented Californians, however, remain excluded from these payments. Their children, who were also excluded from the first and second rebates, will be eligible to get the third rebate if they have Social Security Numbers, but they will not be provided the first or second rebates retroactively. This means that undocumented and mixed status families have received thousands of dollars less in federal aid than other families during the pandemic. California’s Golden State Stimulus replaced a portion of the federal rebates these families were denied, and state leaders could replace even more of those payments using the $26 billion in American Rescue Plan dollars designated for household economic relief.

The ARP Makes Important, but Temporary, Improvements to the Federal EITC

How does the federal EITC change work and who will benefit?

The ARP makes important improvements to the federal Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) for tax year 2021 (for which people will begin filing in early 2022). Specifically, the ARP allows more workers who are not raising children in their homes to qualify for the credit by:

- Lowering the age limit to qualify from 25 to 19 (except for full-time students, who must be at least 24, and certain former foster youth and homeless youth who can be at least 18);

- Eliminating the upper age limit of 64; and

- Raising the income limit to qualify for the credit from about $16,000 to at least $21,000.

In addition, the ARP will nearly triple the maximum credit that workers without qualifying children can receive from $543 currently to about $1,500.

These changes to the federal EITC do not affect California’s Earned Income Tax Credit (CalEITC).

When will Californians benefit from these changes?

In 2022 when they file for tax year 2021.

How much money could Californians receive?

About 2.7 million Californians are expected to benefit from these changes and collectively they could receive around $1.5 billion in 2022, according to estimates by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy.

What does this mean for Californians?

Many Californians with low incomes can expect larger tax refunds next year that will help them to pay for basic expenses. Undocumented Californians, however, will not benefit from these improvements in the federal EITC because they remain excluded from the credit. To help address this exclusion, state leaders could provide a larger CalEITC to undocumented Californians and their families.

Policymakers Temporarily Expand and Increase the Federal Child Tax Credit

How does the Child Tax Credit expansion work and who will benefit?

Federal policymakers made significant, but temporary, changes to the Child Tax Credit (CTC) for tax year 2021. Specifically, the ARP:

- Makes the credit fully refundable, meaning that a family will be able to receive the full credit even if it exceeds the taxes the family owes. Previously, families could only receive a refund equal to a portion of their earnings above $2,500, up to $1,400 per child. As a result, many families with low incomes were left out of receiving the full credit. And because the earnings threshold is eliminated for tax year 2021, families with no earnings can receive the credit.

- Makes 17-year-olds eligible for the credit. Previously, families could only receive $500 for 17-year-old dependents.

- Increases the maximum per-child credit from $2,000 under current law to $3,000 for children age 6 or over and to $3,600 for children under age 6. These additional amounts will begin phasing out starting at $150,000 for married couples, $112,500 for heads of household, and $75,000 for other parents.

- Makes half of the credit available through advance payments from July through December 2021. These payments will be based on the estimated amount of the credit a family is eligible to receive based on its 2020 tax return, or its 2019 return if it did not file in 2020. The ARP limits the amount that a low-income family would be required to repay if it receives advance payments in excess of the amount it qualifies for in tax year 2021 (for example, if a parent receives advance payments related to a child who lived with them in 2020 but no longer lives with them in 2021).

When will Californians benefit from these changes?

Families may receive advance payments beginning in July 2021 equal to one-half of the amount of the total credit a family is estimated to be eligible to receive for tax year 2021. The remainder will be provided in 2022 when families file for tax year 2021.

How much aid will Californians receive and how many will benefit?

This temporary expansion will result in an increase in total Child Tax Credit benefits of $13.7 billion for Californians, with nearly half of those benefits going to the lowest-income 40% — those with incomes under $46,900 — according to estimates from the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP). These changes will benefit 7.9 million to 9 million California children, according to estimates from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) and ITEP, respectively. More than three-quarters (78%) of the children who will benefit in California are children of color, according to CBPP estimates. The CTC changes could lift nearly one-third (32%) of California children out of poverty, with Black and Latinx children seeing the largest reductions, according to estimates from the Public Policy Institute of California. Undocumented children remain excluded from the federal Child Tax Credit, but undocumnted parents may claim the credit for qualifying children who have Social Security Numbers.

Low- and Moderate-Income Families To See Temporary Improvement of Tax Credit

How does the CDCEC change work and who will benefit?

The Child and Dependent Care Expenses Credit (CDCEC) reimburses families for a portion of their expenses for child care or care for another dependent who is incapable of self-care. For tax year 2021 (for which people will begin filing in early 2022), the ARP makes this credit refundable. This means that many low- and moderate-income families who are currently excluded from the credit because they do not owe income tax will be able to receive it, while other families will receive a larger credit than they otherwise would have without this change.

The ARP also substantially increases the size of the credit families can receive from a maximum of $2,100 to $8,000 for two or more dependents and from a maximum of $1,050 to $4,000 for one dependent. The size of the credit will increase because of two changes. First, the new law increases the limit on the amount of annual care expenses eligible for reimbursement from $3,000 to $8,000 for one dependent and from $6,000 to $16,000 for two or more dependents. Second, the bill increases the share of those expenses that can be reimbursed for families with incomes under $183,000, with larger increases for families with the lowest incomes. For example, families with incomes up to $125,000 can have half of their eligible expenses reimbursed under the new law. Currently, they can only have between 20% and 35% of their eligible expenses reimbursed.

The ARP also limits the CDCEC to families with incomes of $438,000 or less, whereas currently there is no upper income limit to qualify for the credit. In addition, it phases out the amount of eligible care expenses that can be reimbursed for families with incomes between $400,000 and $438,000.

These changes to the federal CDCEC do not automatically affect California’s version of the credit.

How much money could Californians receive?

At this time the Budget Center is not aware of any estimates of how many Californians could benefit from the changes to this credit or how much money they could receive.

When will Californians benefit from these changes?

In 2022 when they file for tax year 2021.

What does this mean for Californians?

Many families with low or moderate incomes will receive larger credits next year when they file their taxes, making it easier to pay for basic expenses, including child care.

Support for Workers

Unemployment Benefits Extended Until Early September

How do these extensions work and who will benefit?

Federal policymakers extended several provisions under the American Rescue Plan benefiting jobless workers that were slated to expire in March 2021. For example, the new law:

- Extends through September 6 the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) program, which provides unemployment benefits to jobless workers who don’t qualify for regular unemployment benefits, such as people who are self-employed;

- Increases the maximum number of weeks of benefits available through the PUA from 57 weeks to up to 86 weeks;

- Increases the maximum number of weeks of benefits available through the Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC) program, which benefits jobless workers who exhaust regular unemployment benefits, from 24 weeks to 53 weeks; and

- Extends the Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (FPUC) through September 6, which provides an additional $300-per-week benefit on top of what workers receive through either their state’s regular UI program or the PUA.

An Employment Development Department chart shows the various federal unemployment benefits available to jobless workers during the pandemic and how long those benefits last.

When will Californians benefit from these changes?

The Employment Development Department has indicated that it will need until the middle of April to implement the unemployment benefit extensions.

How much money could Californians receive?

The amount of money Californians could receive from federal unemployment benefit extensions is difficult to estimate because it depends on how long it takes workers to find jobs as the economy recovers. The Legislative Analyst’s Office roughly estimates that Californians could potentially receive around $40 billion from these extensions if the number of benefit claims continues a moderate decline through September.

What does this mean for Californians?

California’s unemployment rate is still twice as high as it was before the pandemic began, and women as well as Black and Latinx workers remain more likely to be out of work than men and white workers. The extension of federal unemployment benefits will help the many Californians who remain out of work due to the pandemic pay for basic expenses. Unfortunately, however, these benefit extensions will expire this fall when unemployment will likely still be high, particularly for workers who have been hit hardest by the recession. This means that some Californians are likely to still need additional support meeting basic needs later this year.

First $10,200 in Unemployment Benefits Excluded from Federal Income Tax

How does this exclusion of benefits work and who will benefit?

The ARP excludes the first $10,200 in unemployment benefits received in 2020 from federal income tax for filers with adjusted gross incomes less than $150,000. This will reduce or eliminate many filers’ tax liability. Without this provision, many people who received unemployment benefits during the pandemic would face unexpectedly large tax bills when they filed federal income taxes this year. (Unemployment benefits are not subject to California’s income tax so they will not face surprise tax bills on these benefits when they file state taxes.)

When will Californians benefit from this change?

People who might benefit from this change in law should wait to file federal income taxes until the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) updates tax forms to reflect this change. It is not yet clear whether people who filed their taxes already will have to file amended returns in order to benefit from this change.

How much money could Californians receive?

At this time the Budget Center is not aware of any estimates of how many Californians could benefit from this change or how much money they could receive.

What does this mean for Californians?

Many Californians who lost work last year will owe less in federal income taxes this year and could also get larger tax credits than they otherwise would have. That’s because this change in federal law will reduce some tax filers’ federal adjusted gross income (AGI) in tax year 2020, making them eligible for larger tax credits, including the federal Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and California’s Earned Income Tax Credit (CalEITC). It is not yet clear whether people who already filed their taxes for tax year 2020 will have to file amended returns in order to receive the proper amount of the credits they are now owed. The IRS is currently advising tax filers not to file amended returns until further notice.

Tax Credits Extended for Businesses Voluntarily Offering Paid Time Off to Workers

How does the American Rescue Plan help workers and businesses with paid time off during the pandemic?

The federal Families First Coronavirus Response Act passed in March 2020 temporarily addressed US workers’ lack of paid time off by requiring certain employers to provide both paid sick days and paid leave for COVID-related reasons through December 31, 2020. Businesses received payroll tax credits to cover the cost of the paid time off for their workers. The new American Rescue Plan extends these refundable tax credits to businesses who continue to voluntarily provide paid time off through September 30, 2021. However, businesses are no longer required to provide paid time off under the newly enacted federal law.

Which organizations and workers can benefit from the new law?

Organizations with less than 500 employees are eligible for the payroll tax credits, which offset the cost of providing paid time off to workers. Eligible organizations include businesses, nonprofits, state and local governments, and self-employed people, as well. To qualify for tax credits, employers must offer leave to all workers, including workers paid low wages, with part-time schedules, and newly-hired workers. Workers employed by an organization voluntarily providing benefits, can take paid time off for a variety of COVID-related reasons under the new law:

- Unable to work because they are subject to quarantine, have been advised to quarantine, are getting tested for or are waiting for test results for the virus;

- Sick with COVID-19 or experiencing symptoms of the virus;

- Absent from work to receive the vaccination or recovering from the vaccination;

- Workers caring for someone who is sick, is experiencing COVID-19 symptoms, or is in quarantine due to the virus; or

- Workers caring for a child whose school or child care provider is closed due to the virus.

Workers and employers are able to utilize paid sick time and receive the federal tax credits even if workers have already used paid sick days under the Families First provisions prior to April 1, 2021.

What are the benefits for paid time off?

Employers will receive payroll tax credits for voluntarily providing paid sick days and paid leave from April 1, 2021 through September 30, 2021. Workers will be paid while away from work as follows:

- Workers using paid sick days due to their own illness, quarantine, or vaccination will receive payments equal to 100% of their wages up to $511 per day or $5,110 total for ten days.

- Workers using paid sick days to care for a sick family member or a child will receive payments equal to two-thirds of their regular pay, up to $200 per day or $2,000 total for ten days.

- Workers using paid leave to care for themselves or a family member will receive up to 12 weeks of paid time off at two-thirds of their regular pay capped at $200 per day and $12,000 total.

What does this mean for Californians?

Employers are not required to provide paid time off during the public health crisis under the new federal law, which would generally limit workers’ ability to care for themselves or their families during the pandemic. However, Governor Newsom just signed into law a bill that requires employers with 25 or more workers to provide 10 emergency paid sick days to care for themselves or a family member until September 30, 2021. In some cases, California’s state disability insurance program and paid family leave program can help fill some gaps for workers who need additional time off during the pandemic if their employer is not voluntarily providing paid time off. When the state and federal provisions expire, employers in California will be required to provide just three paid sick days to their workers.

Economic Security

Policymakers Provide Significant Boost in One-Time Funding, Create Opportunity to Build Strong Child Care Foundation

How much funding is available and how much will California receive?

The American Rescue Plan provides $40 billion to support early care and education, including funding for providers, workers, and their families. This includes:

How can the funding be used?

Leaders in California can use the new federal funding in the following ways:

- The $1.4 billion in Child Care and Development Block Grant funding boosts support for California’s subsidized child care and development system. State policymakers have flexibility in using the one-time funding, such as providing additional spaces for children in subsidized programs, increasing provider payment rates during the public health emergency, or waiving fees paid by many families receiving subsidized care. While subsidized child care is typically reserved for families with low and moderate incomes, this bill allows states to expand eligibility for subsidized care to essential workers regardless of income.

- The $2.3 billion in child care stabilization funds are to be distributed as grants to eligible child care providers — not just those participating in the state’s subsidized system — including providers who have remained open and those who closed due to the pandemic. Grants can be used for a variety of expenses, such as paying wages, facility expenses, COVID-related supplies and equipment, and mental health support for children and staff. This includes reimbursement for extra costs covered by providers in the last year as a result of the pandemic. Providers receiving grants are to follow public health guidelines, maintain employee wages, and provide relief from child care fees for families struggling to afford care, if possible.

- The $105 million in Head Start funding will go directly to Head Start providers in California to maintain services during the public health crisis. Funds will be available through September 2022.

- Ongoing funding received through the Child Care Entitlement to States will increase support for subsidized child care in California and can be used for similar purposes as Child Care and Development Block Grant funding, with some stipulations. In order to receive this funding, states must provide matching funds up to a certain amount, but this requirement is waived for the 2021 and 2022 federal fiscal years.

Generally, state policymakers may not use the funding for subsidized child care or stabilization funds to replace existing dollars for child care in California.The funds can only be used to supplement current spending.

What are the timelines for using federal child care relief funds?

California leaders have various timelines for utilizing the one-time federal child care relief funds that are to be administered by the state. Specifically, state leaders must:

- Determine how the $1.4 billion in Child Care Development Block Grant funds will be spent by September 2023 and expend these funds by September 2024.

- Provide grants to providers using the $2.3 billion in child care stabilization funds. After 10% is withheld for administrative expenses, the state must commit at least 50% of these funds within nine months of enactment or notify the federal government of the inability to do so. This means that the state must commit roughly $1 billion in grants to child care providers across the state via a new grant program by December 11, 2021.

What does this mean for California?

Child care is a critical component of the state and nation’s economic infrastructure, but chronic underinvestment by both the state and federal government has resulted in a fragile system that has not been able to weather the shocks of the COVID-19 health and economic crisis. The American Rescue Plan is the third round of federal child care relief funds provided to states since the beginning of the pandemic. California first received $350 million as part of the CARES Act in March 2020, but the distribution of the first round of federal child care relief funds was subject to administrative delays The state also received $964 million as part of the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021 which was enacted in December 2020. While state policymakers have determined how $402 million of the $964 million allocated through the Appropriations Act will be spent, $562 million will likely be included in the 2021-22 budget agreement which begins on July 1. It is critical that state leaders fast track a plan to quickly and equitably distribute funding from both the second and third round of funding while minimizing delays in providing relief for families and providers.

These one-time federal relief dollars provide a unique opportunity to create a firmer foundation for the child care sector in California, while also providing fiscal relief for both parents and providers during the COVID-19 crisis. However, it will take significant ongoing investments from both the state and federal government to adequately fund the child care sector beyond the current health emergency and recession. Ongoing funding is necessary to ensure that children have a safe place to learn and grow, working parents have access to affordable child care, and providers are paid fair and just rates.

Federal Policymakers Extend Food Assistance but Still Exclude Some Californians

How does the American Rescue Plan extend CalFresh benefits?

In December, federal policymakers provided a 15% increase in monthly food assistance benefits through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), also known as CalFresh in California. The ARP maintains this increase, which was set to expire in June, and extends it through September 30, 2021. The relief package allocates $355 million to California to support this extension, providing an average monthly benefits increase of $28 for Californians who participate in CalFresh.

How else does the ARP support nutrition?

The new federal relief package also extends the Pandemic EBT (P-EBT) program through the end of the COVID-19 public health emergency. P-EBT provides grocery benefits to replace meals that children would otherwise receive at school or at child care.

Federal legislators also allocated funds to the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). These funds will support improved outreach to participants and increased access to fruits and vegetables.

How will this assistance benefit Californians and who is left out?

The strengthened food assistance in the new relief package will address food insecurity in California, which has worsened during the COVID-19 recession. About 1.9 million households with children (15.9%) reported sometimes or often not having enough food to eat during a four-week period in late June and July. This includes more than 1 in 5 of Latinx households and Black households with children reporting sometimes or often not having enough to eat (21.9% and 20.2%, respectively). The federal relief package will help many of these Californians as they struggle with food hardship. However, with the exception of asylees, refugees, and some other “qualified” immigrants, most immigrants remain excluded from receiving CalFresh.

California Will Receive Additional Funds Under CalWORKs to Help Families with Children

How much funding is available and how much will California receive?

The American Rescue Plan created a $1 billion Pandemic Emergency Assistance Fund to allow states, territories, and tribes to provide families with short-term emergency benefits. The fund will be administered through Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program, known as CalWORKs in California.

- 92.5% of the funds (after subtracting $2 million reserved for federal administration) will be distributed to states according to a formula which is equally weighted based on the state’s share of the child population and its prior share of spending on specific TANF categories. California will receive $203.8 million.

- 7.5% of funds will be distributed to US territories and tribes.

How can the funding be used?

States, territories, and tribes can use the funds only to provide families with non-recurrent, short term cash or in-kind benefits (no more than four months) to address specific crises or episodes of need — not to support ongoing needs. Examples are short-term cash assistance, emergency housing vouchers, utility payments, food aid, and burial assistance. The funds can not be used for tax credits, child care, transportation, or education and training.

How soon will the funding arrive and what is the timeline for using it?

States must request funding within 45 days of the enactment of the American Rescue Plan, or April 25, 2021. Any funds that remain unspent by the end of September 2022 will be reallocated to other states, territories, and tribes, which will then have to use the funds within one year of receipt.

What does this mean for California?

Many California families with children, particularly Black and Latinx families, have faced significant hardship during the pandemic, including having difficulty covering basic expenses and facing food insecurity. The Pandemic Emergency Assistance funds will give the state the ability to address urgent needs of California families with children who have low incomes. The state has the flexibility to use the funds in various ways, including providing short-term supplemental assistance to families already receiving CalWORKs cash assistance, assisting other families demonstrating financial hardship — such as those receiving CalFresh nutrition benefits — and providing emergency cash or in-kind aid to families ineligible for other relief.

Health

The American Rescue Plan Substantially Cuts Consumers’ Costs for Private Health Insurance

What new federal assistance is available to people who buy private health insurance?

The ARP makes private health insurance more affordable for consumers. This is expected to encourage people to keep their coverage or — for those who are uninsured — to newly enroll in coverage. Specifically, the law:

- Expands federal subsidies for people who buy coverage through an online health insurance marketplace, such as Covered California. This additional federal assistance will lower the cost of monthly premiums — in some cases to $0 — for millions of people through December 2022, when this new provision expires (see next section).

- Allows people who receive unemployment insurance (UI) benefits to sign up for certain health plans through an online health insurance marketplace with no monthly premium. This provision expires at the end of 2021.

- Makes job-based “COBRA” coverage more affordable by allowing people who lose their job or have their hours reduced to keep or re-enroll in their employer-based health plan with no monthly premium. This provision expires on September 30, 2021.

How many Californians are expected to benefit from this new federal assistance?

According to state estimates, almost 3.1 million Californians qualify for the new federal premium subsidies through Covered California. Of these Californians:

- 1.4 million are already enrolled in a Covered California plan and will automatically qualify for the new premium reductions, without any action needed on their part.

- 430,000 have private insurance “off-exchange” (not through Covered California) and will qualify for the new premium reductions if they switch to a Covered California plan.

- 1.2 million are uninsured, but will qualify for the new premium reductions if they sign up for a Covered California plan.

These numbers do not account for UI recipients, who are eligible for certain Covered California plans with a $0 premium, or for people who qualify for the COBRA subsidy to continue their job-based coverage with a $0 premium. It is unclear how many Californians fall into these two categories.

What financial impact will this new federal assistance have on Californians who purchase health insurance through Covered California?

The cost of plans purchased through Covered California will decline for consumers at all income levels. Many households with lower incomes will see the cost of their monthly premiums drop to less than 2% of their income, including down to $0. In addition, premiums will top out at 8.5% of income — a level that applies to households with incomes above 400% of the federal poverty line ($86,880 for a family of three). These higher-income households are not eligible for any federal subsidies under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which President Obama signed into law in 2010.

These changes will allow Californians who buy insurance through Covered California to save potentially thousands of dollars on premiums through the end of 2022. Families and individuals can use these resources to help pay for housing, child care, and other necessities during the recession as well as to build up their savings to help meet future expenses.

Premium reductions available under the ARP include the following:

- A family of four earning 150% of the poverty line ($3,275 per month) will have no monthly premium for a Covered California plan. Prior to the ARP, this family would have contributed 4.14% of income, or $136 per month. Result: savings of around $2,700 from May 2021 to December 2022.

- A couple earning 200% of the poverty line ($2,873 per month) will contribute 2.0% of their income, or $57, toward their monthly premium for a Covered California plan. Prior to the ARP, this couple would have contributed 6.52% of income, or $187 per month — a difference of $130 per month. Result: savings of roughly $2,600 from May 2021 to December 2022.

- An individual earning 300% of the poverty line ($3,190 per month) will contribute 6.0% of their income, or $191, toward their monthly premium for a Covered California plan. Prior to the ARP, this individual would have contributed 8.9% of income, or $284 per month — a difference of $93 per month. Result: savings of about $1,860 from May 2021 to December 2022.

Federal Policymakers Provide Critical Funding for Public Health Infrastructure

How much funding is available and how much will California receive?

Federal lawmakers authorized almost $93 billion for public health efforts in response to COVID-19, such as vaccine distribution, testing, contact tracing, and surveillance. The bill also makes critical investments to expand the public health workforce, including hiring additional contact tracers, nurses, epidemiologists, community health workers, and other essential staff to address COVID-19. An estimated $4.7 billion will be allocated to California.

How can the funding be used?

In California, the public health funding will be allocated for the following purposes:

- $3.2 billion for COVID-19 testing, contact tracing, lab capacity, and other efforts to strengthen and expand activities and workforce related to genomic sequencing, analytics, and disease surveillance.

- $1.1 billion for community health centers to administer vaccines and conduct COVID-19 testing and contact tracing.

- $800 million to expand the state and local public health workforce, including case investigators, contact tracers, social support specialists, community health workers, public health nurses, disease intervention specialists, epidemiologists, program managers, laboratory personnel, informaticians, communication and policy experts, and any other positions that are required to prevent, prepare for, and respond to COVID-19.

- $700 million for vaccine distribution, administration, and supplies (e.g., mobile vehicles and equipment to administer vaccinations). Funds can also be used to promote vaccinations or to hire and train staff to administer vaccines.

What is the timeline for using the funds?

Most of this funding is available until expended.

What does this mean for California?

Public health systems in California and at the national level have long been under-resourced and were inadequately prepared to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, which has brought devastation to many families and communities. Communities of color across the state — particularly Black, Latinx, and Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander Californians — have experienced higher rates of illness and death from COVID-19 due to historic and ongoing structural racism that deny many communities the opportunity to be healthy and thrive. The intersection of the COVID-19 pandemic as well as structural racism has underscored the need to strengthen public health systems. While new funding for public health infrastructure brings the state closer to overcoming the pandemic, California leaders must prepare for and respond to other population health threats, including racism. Given that the goal of public health is to promote and protect the health of people and communities, public health leaders can also begin to minimize, neutralize, and dismantle the systems of racism that create inequalities in health for Californians.

The American Rescue Plan Strengthens California’s Medicaid Program (Medi-Cal)

What changes does the ARP make to Medicaid?

Medicaid provides health care coverage for people with low incomes. The program is funded with both federal and state dollars and is known as Medi-Cal in California. ARP provisions that strengthen the Medicaid program and will benefit Californians include the following:

- Allows states to extend to 12 months pregnancy-related, postpartum Medicaid coverage, well beyond the current 60-day limit. States that take up this option would be required to provide full Medicaid benefits to women both during pregnancy and the 12-month postpartum period. This option would take effect on April 1, 2022, and would last for five years.

- Builds on last year’s “Families First” federal relief package by directly requiring state Medicaid programs to cover COVID-19 testing, treatment, and vaccines at no cost to individuals. These requirements continue for approximately 15 months after the end of the COVID-19 public health emergency. During this same period, the federal government will pay the full cost for COVID-19 vaccine coverage and administration.

- Temporarily boosts federal Medicaid funding for home and community-based services (HCBS), which help people remain in their homes and avoid institutional care. Each state will receive a 10 percentage-point increase to their federal matching rate for HCBS, except that the resulting federal matching rate may not exceed 95%. These increased funds are available for one year, beginning on April 1, 2021, and must be used to supplement, rather than to supplant, existing state funding for HCBS. Allowable uses of these temporary federal funds include, but are not limited to, home health care, personal care services, and rehabilitative services, including those related to behavioral health.

- Temporarily provides 100% federal Medicaid funding for health services provided through Urban Indian Organizations and Native Hawaiian health care systems. This full federal funding is available for two years, beginning on April 1, 2021. California has a number of Urban Indian Organizations, including in Bakersfield, Fresno, Los Angeles, Oakland, Sacramento, and San Diego.

What would these changes mean for California?

The ARP health care provisions build on efforts to increase access to health care services, improve health outcomes, and overcome the COVID-19 pandemic. Under this law, people who receive health care services through Medi-Cal could continue to receive services up to a year after giving birth. Currently, this extension is limited to Californians who are diagnosed with a maternal mental health condition, such as postpartum depression. This policy change is critical in addressing maternal mortality and maternal mental health conditions, which disproportionately impact Black women and other women of color. In addition, the funding support for HCBS will help individuals live at home instead of in a nursing facility or another Medi-Cal funded institution. Without this investment, these individuals may not be able to remain in their homes, putting them at risk of being placed in group care facilities at a time when these settings may continue to pose a risk of contracting or dying from COVID-19. Lastly, the boost to Urban Indian Organizations and Native Hawaiian health care systems will help to improve health outcomes among American Indians across the state. Targeting investments to communities that have been hit hard by the COVID-19 pandemic due to historic and ongoing structural racism is an important step in advancing health equity.

Federal Policymakers Allocate Funding to Address Behavioral Health Needs that Have Increased During Pandemic

How much funding is available and how can it be used?

The ARP makes critical investments in behavioral health services — mental health care and/or treatment for substance use — which are primarily provided by counties, with funding from the state and federal governments. Specifically, the ARP allocates nearly $4 billion one-time funding for behavioral health prevention, services, and workforce training. This includes:

- $1.5 billion in block grants for community-based mental health services. This funding will support state efforts to address needs and gaps in existing treatment services for children and adults with serious mental health conditions. Funds must be expended by September 30, 2025.

- $1.5 billion in block grants for community-based prevention and treatment of substance use. These funds will support state efforts to address ongoing prevention and treatment services for substance use. Funds must be expended by September 30, 2025.

- $420 million for Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics (CCBHCs). California currently hosts 11 CCBHCs, which provide or coordinate a range of mental health and substance use services with an emphasis on 24-hour crisis care, evidenced-based practices, and integration with physical health care. CCBHCs serve people with mental illness or substance use disorders of any severity (mild to moderate to severe), regardless of their ability to pay.

- $100 million to expand the behavioral health workforce through expanding education and training.

- $80 million for community-based funding for local behavioral health and substance use disorder services.

- $80 million to implement robust behavioral health and wellness education and awareness campaigns for health care professionals and first responders.

- $60 million for addressing behavioral health needs in children and youth, specifically for Project Advancing Wellness and Resiliency in Education (AWARE) state education agency grants, youth sucide prevention grants, and the National Child Traumatic Stress Network.

The law additionally provides funding for community-based mobile crisis intervention services, which are designed to respond to individuals experiencing a mental health crisis in a community setting. Meeting certain criteria, states will have a new option to provide these services with 85% federal matching funds for the first 3 years.

What is the timeline for using this funding?

There is no deadline to spend funds unless otherwise noted.

What does this mean for Californians?

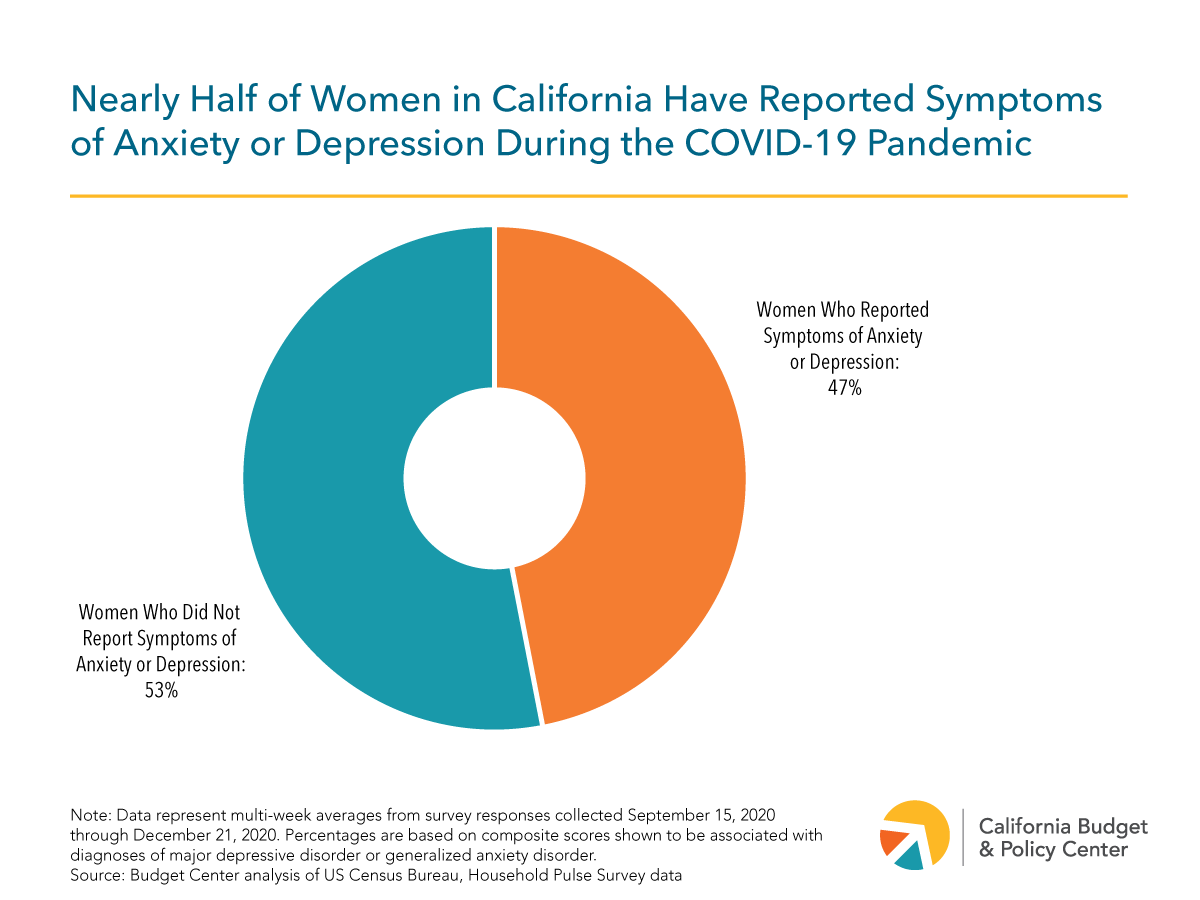

The Biden Administration’s funding for behavioral health services as well as the behavioral health workforce is a critical step in supporting mental health and substance use needs, which have increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many individuals in California and across the nation are dealing with stress, isolation, economic hardship, illness, and the loss of loved ones. During the pandemic, the share of individuals in the US experiencing symptoms of anxiety and/or depression has more than tripled. In California, nearly 2 in 5 adults reported symptoms of anxiety or depression during a two week period in March 2021. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, millions of Californians were coping with mental health or substance use disorders and many confronted challenges in accessing services. State and federal policymakers must recognize that even after stay-at-home orders are lifted and economic recovery progresses, the work to support mental health and well-being will be far from over. Additionally, policymakers should consider the racial equity implications in future budget and policy deliberations related to behavioral health given that Californians of color have been disproportionately impacted by the pandemic as well as the recession.

Housing & Homelessness

Federal Policymakers Provide Emergency Assistance for Renters and Homeowners

How does the American Rescue Plan help struggling renters stay in their homes?

The ARP helps renters who are struggling to meet their housing needs, including paying for rent and utilities. This support includes:

- $21.6 billion for emergency rental assistance — California will receive an estimated $2.2 billion. These funds will help struggling renter households pay back rent accumulated since April 2020 and keep up on current rent, for a maximum of 18 months of support. Households must have incomes below 80% of Area Median Income (AMI), have lost income or experienced other financial hardship due to COVID-19, and face a risk of homelessness or housing instability. Californians who are undocumented or live in mixed-status households are eligible for assistance. Funds will be available through September 2025. These funds add to the $25 billion ($2.6 billion for California) in emergency rental assistance included in the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021 enacted in December 2020. The timeline for using these earlier emergency rental assistance funds was also extended through September 2022.

- $5 billion for emergency housing vouchers — California will receive an estimated $500 million. Housing vouchers will provide longer-term rental assistance for Californians who are at risk of or currently experiencing homelessness or who are fleeing domestic violence or human trafficking. These vouchers, administered by public housing authorities, can be used by a household for as long as that household requires assistance but cannot be reissued to new households after September 2023.

- $5 billion for utilities assistance — California will receive an estimated $200 million. California renters with low incomes will receive assistance covering utility costs including electricity, gas, and water. Funds will be distributed through the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) and through the Low-Income Household Water Assistance Program (LIHWAP) that was newly created through the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021.

How does the ARP help struggling homeowners stay in their homes?

The American Rescue Plan includes $10 billion for homeowners experiencing financial hardship due to COVID-19 to help them avoid foreclosure and displacement. California will receive an estimated $1 billion. This financial assistance can be used for mortgage payments, utilities, insurance, and other housing costs related to preventing foreclosure. At least 60% of the funds must be targeted to homeowners with incomes equal to or less than 100% of AMI or 100% of median income for the United States, whichever is greater. Funds are available through September 2025.

How else does the ARP address housing needs?

The American Rescue Plan includes $750 million for tribal nations and Native Hawaiians to provide emergency housing assistance for Native American, Alaskan Native, and Native Hawaiian households living in tribal areas or on home lands, adding to funds provided in the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021. Also included is $100 million for emergency rental assistance for households living in federally-financed rural housing, available through September 2022, as well as $100 million for housing counseling services and $20 million to enforce fair housing laws.

What does this mean for California?

These one-time federal funds offer critical support to help Californians who are struggling to afford housing costs, which is especially important for renters, households with lower incomes, Black and Latinx Californians, and Californians who are undocumented — who faced serious housing affordability challenges even before the pandemic, and are likely to continue to face these challenges after COVID-19 as well. Emergency rental assistance and housing vouchers are especially important with California’s eviction moratorium currently set to expire at the end of June 2021.

Policymakers Provide Flexible One-Time Funding for Individuals Experiencing Homelessness

How much funding is available and how much will California receive?

To address the needs of individuals experiencing homelessness, the American Rescue Plan provides $5 billion in flexible funding distributed through the HOME Investment Partnerships Program. California will receive an estimated $500 million.

How can the funding be used?

Funds can be used for a variety of activities, including developing affordable or supportive housing, providing short-term rental assistance, and providing support services for people experiencing or at risk of homelessness. Funds can also be used to acquire commercial properties such as hotels and motels in order to convert them to non-congregate emergency shelter, affordable housing, or supportive housing, similar to California’s Homekey program.

What are the timelines for using the funds?

The homelessness assistance funds are available through September 2025.

What does this mean for California?

These one-time federal funds will help California meet the needs of the more than 160,000 Californians facing homelessness each night. Meeting these needs is especially critical during the pandemic, which exacerbates the health and public health risks for people experiencing homelessness. At the same time, effectively addressing California’s homelessness crisis over the long term — including the particularly inequitable impact on Black Californians — will require ongoing support, through state and federal funds, at a scale that meets the size of the challenge.

Education

American Rescue Plan Provides Aid to Support K-12 Education

How much K-12 education funding will California receive from the American Rescue Plan (ARP)?

The ARP provides $122 billion in fiscal aid to local K-12 school districts and state departments of education based on the proportion of Title I, Part A funding that each state received in 2020. Title I, Part A funding is determined primarily by the number and share of children in local K-12 school districts below the federal poverty line. California will receive $15.1 billion of these ARP dollars, including:

- A minimum of $13.6 billion that will be distributed directly to local K-12 school districts, county offices of education (COE), and charter schools – local educational agencies (LEAs) – in proportion to the share of Title I, Part A dollars that each of these LEAs received in 2020.

- No more than $1.5 billion of that will be reserved for the California Department of Education (CDE).

How can the funding be used?

At least 20% of the additional federal funding distributed to LEAs must be used for evidenced-based interventions that are responsive to students’ social, emotional, and academic needs and address the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on underrepresented student groups such as English learners and children from low-income families. The remaining funding distributed to LEAs may be used for a wide range of activities to address needs arising from the pandemic such as:

- hiring new staff;

- purchasing educational technology for students that aids in substantive educational interaction between students and classroom instructors;

- planning and implementing activities related to summer learning and supplemental after-school programs; and

- improving indoor air quality.

In federal fiscal years 2021-22 and 2022-23, LEAs that receive the new federal funds may not reduce funding per student from state and local sources, or staffing levels, for any of its high-poverty schools – defined as the 25% of schools that serve the highest percentage of economically disadvantaged students – by an amount greater than reductions per student for the entire LEA.

How soon will the funding arrive and what is the timeline for using it?

On March 24, 2021, the US Department of Education (DOE) released $10 billion of the $15.1 billion California will receive from the ARP. The remaining dollars will become available after California submits a plan for how it will use the funds to the US DOE. The additional funding for K-12 school districts, COEs, charter schools, and the CDE will be available to spend through September 30, 2024.

What does this mean for California?

California’s K-12 school districts, COEs, and charter schools will receive a sizable increase in federal funding. By targeting dollars to LEAs with large shares of economically disadvantaged students, and providing flexibility in how the funds can be used, the new federal funding means LEAs will have significant financial resources to support students who have been disproportionately affected by the pandemic. However, because the funding for K-12 education is a one-time boost, LEAs face challenges that include how to effectively use the large amount of additional dollars and avoid hardships when they are no longer available.

Emergency Relief Provides Financial Aid to Students Most Harmed by the Pandemic

How much funding is available and how much will California receive?

Federal lawmakers authorized nearly $40 billion dollars in grants that will go directly to institutions of higher education (IHEs). The funds include $3 billion for Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) and other Minority Serving Institutions (MSIs). California IHEs will receive an estimated $5 billion and will be allocated based on the relative shares of:

- Federal Pell Grant recipients;

- Non-Pell Grant recipients; and

- Federal Pell and non-Pell Grant recipients exclusively enrolled in online education prior to the pandemic emergency.

How can the funding be used?

IHEs receiving funds must allocate at least 50% of the funds as emergency financial aid grants to students — with the only exception of for-profit IHEs, which will have to spend 100% of the funds on student aid. Grants to students can be used for any component of the student’s cost of attendance and emergency costs due to the pandemic, such as tuition, food, housing, health care, and child care. IHEs are responsible for determining how to award grants to students, but they are required to prioritize students with the greatest need. Allocations to not for profit IHEs include flexible funds that can be used for immediate needs related to the health emergency, including:

- Lost revenue;

- Additional financial aid grants to students;

- Reimbursement for expenses already incurred;

- Technology costs due to distance learning;

- Faculty and staff professional development; and

- Payroll.

Additionally, IHEs are required to use a portion of their dollars to implement evidence-based practices to mitigate COVID-19. IHEs are also required to conduct direct outreach to students about the opportunity for a financial aid adjustment for more aid due to recent unemployment of a family member or changes in financial circumstances. Provisions in the ARP do not appear to restrict an IHE’s ability to provide aid to students based on their immigration status.

How soon will the funding arrive and what is the timeline for using it?

The ARP specifies that funds will be available for use by IHEs through September 30, 2023.

What does this mean for California?

The federal aid earmarked for higher education means that California colleges and universities will be able to provide direct aid to students most harmed by the pandemic, especially those experiencing housing and food insecurity, loss in household income, and other hardships due to the health crisis. The ARP will also help colleges and universities return to in-person instruction and address immediate needs related to the pandemic, such as increased costs and lost revenues. Lastly, the financial resources available to IHEs over the next couple of years will help address the prolonged and disproportionate effects of the pandemic for low-income households and communities of color.