Californians from all corners of the state — of all races and ethnicities, genders, ages, and abilities — deserve to be able to afford the basics and thrive in their communities, and a more equitable tax and revenue system would help make that a reality. All Californians share in the responsibility of paying taxes to support public services that keep the state running and help families to be financially secure. This responsibility also extends to the corporations earning profits in the state. These corporations benefit from the fruits of the state’s public investments, which provide them with an educated workforce; a transportation infrastructure to transport goods; a functional legal system, and much more.

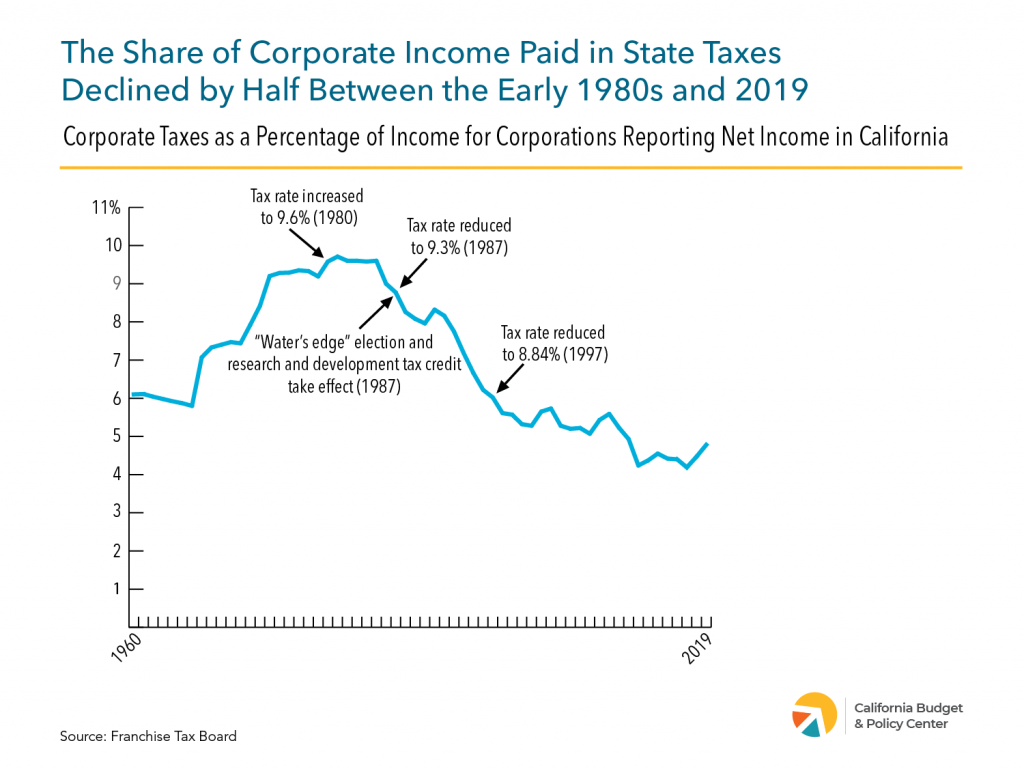

As millions of people struggle with the high costs of living and recovery from the health and economic effects of the pandemic, corporate profits have surged to historic new highs in recent years. However, corporations now pay just about half of what they did in the early 1980s in California taxes as a share of their income. This decline is a result of cuts to the corporate tax rate and the creation and expansion of corporate tax breaks. In addition, corporations were granted significant federal tax cuts as part of the “Tax Cuts and Jobs Act” of 2017, and some corporations even manage to pay nothing in federal taxes.

Policymakers have many options to ensure that profitable corporations are adequately contributing to California’s tax revenues and supporting the services that we all benefit from. These options include — but are not limited to — increasing tax rates for the most profitable corporations, ensuring that all profitable corporations pay a minimum level of taxes, and combating corporate tax avoidance. Increasing tax rates and limiting tax breaks for corporations only affects those corporations that make profits in California, so these actions will not harm struggling businesses that are operating in the red.

Increasing corporate tax revenues would provide more resources to support solutions to the most significant challenges facing Californians, such as unaffordable housing, child care, and health care costs.

1. Raise Corporate Tax Rates for the Most Profitable Corporations

When individuals and families pay their taxes, higher levels of income are subject to higher tax rates. This is not the case for corporations, which generally pay the same official tax rate regardless of the size of their profits.1Some types of corporations are subject to different rates, such as banks and other financial institutions, which pay an additional 2% in state tax because they are exempt from local taxes that other businesses pay. Corporations that are organized under Subchapter S pay only a 1.5% rate, but their shareholders pay personal income taxes on their shares of the business’ income. Additionally, the effective tax rate — the share of overall income paid in tax — varies from corporation to corporation based on the extent to which they are able to take advantage of corporate tax breaks. Just as a small share of households receive an outsized share of total income in the state, a small share of corporations earn the majority of profits in California. Corporations with California profits of more than $10 million represented 0.3% of corporations operating in the state but made 62% of all statewide corporate profits in 2019, according to Franchise Tax Board data.2Franchise Tax Board, Corporation Tax Annual Report, Tax Year 2019, Table C-8, https://data.ftb.ca.gov/California-Corporation-Tax/CORP-Annual-Report-2020/6mcf-cr69 Adding a surtax — a higher tax rate — on just these corporations could raise substantial revenues without affecting the vast majority of businesses.3Jonathan Kaplan, Why Aren’t Large Corporations Paying Their Fair Share of Taxes and What Can California Policymakers Do About It?, (California Budget & Policy Center, April 2021), 6, https://calbudgetcenter.org/app/uploads/2021/03/IB-FP-Corporate-Taxes.pdf.

Of course, policymakers could set the threshold for a surtax lower than $10 million, or move to a graduated corporate tax structure where higher increments of profits are subject to higher rates. Several states already have graduated corporate tax structures and a few states have enacted temporary surtaxes on highly profitable corporations. Asking those corporations that are immensely profitable to contribute more to support state services would improve tax fairness and protect small and struggling businesses.

2. Ensure That Corporations Pay an Adequate Minimum Level of State Taxes

Based on the premise that corporations that take advantage of certain tax preferences should still pay a minimum level of taxes, the state put into place different rules to compute tax liability for these corporations.4This alternative minimum tax system is in addition to the $800 “minimum franchise tax” that must be paid by all corporations incorporated in, registered in, or doing business in California. However, state law still allows corporations to use many tax credits to reduce the minimum tax they would owe under these rules. This includes the research and development credit — the state’s largest credit, representing about 4 in 5 dollars of the total cost of California’s corporate tax credits.5Franchise Tax Board, Corporation Tax Annual Report, Tax Year 2019, Table C-7. As a result, California does not actually ensure that profitable corporations pay an adequate minimum level of tax. Policymakers could strengthen the minimum tax by not allowing credits to reduce a corporation’s tax liability below the minimum tax.6Specifically, credits could not be allowed to reduce taxes owed below the “tentative minimum tax,” which is the amount resulting by applying a 6.65% tax rate (or 8.65% for financial institutions) to an alternative income calculation which removes certain tax preferences. Credits could also not be allowed to reduce the “alternative minimum tax,” which is the additional amount that a corporation generally must pay when their tentative minimum tax exceeds their regular tax liability.

Another approach would be to simply limit the extent to which a corporation can use tax credits to reduce their tax bill in any given year. For example, California temporarily prohibited businesses from using more than $5 million in tax credits — excluding the low-income housing credit — to reduce their tax liability in 2020 after the COVID-19 pandemic hit when the state’s finances were expected to suffer. Policymakers could institute such a limit on a permanent basis, or limit the credits that can be claimed in a given year to a specific percentage of the tax that a corporation would otherwise owe. For example, credits could be limited to one-half of a corporation’s pre-credit tax liability in any given tax year.

3. Limit the Ability of Corporations to Avoid State Taxes by Using Tax Havens

Corporations doing business in multiple countries can minimize or even eliminate the taxes they owe to the US federal and state governments by shifting their profits into subsidiaries in jurisdictions with low or zero tax rates, known as tax havens. One recent estimate suggests that about one-quarter of the profits of US multinational corporations are booked abroad, and that about half of these foreign profits are booked in tax havens.7The authors also estimate that around 13-15% of the total worldwide profits of US corporations were booked in tax havens across 2015-2020, which they note represents a historically high level. Javier Garcia-Bernardo, Petr Janský, and Gabriel Zucman, Did The Tax Cuts And Jobs Act Reduce Profit Shifting By US Multinational Companies? (National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 30086, May 2022), 3, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w30086/w30086.pdf. Much of these shifted profits are not actually earned in these foreign jurisdictions, but have been artificially shifted out of the United States using creative accounting techniques.8One such technique is transferring intellectual property rights — such as patents and trademarks — to their foreign subsidiaries, which can then charge the US parent company for the use of that intellectual property. See, for example, Ana Maria Santacreu and Jesse LaBelle, “Profit Shifting Through Intellectual Property,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Economic Synopses, no. 22 (July 2022), https://doi.org/10.20955/es.2022.22.

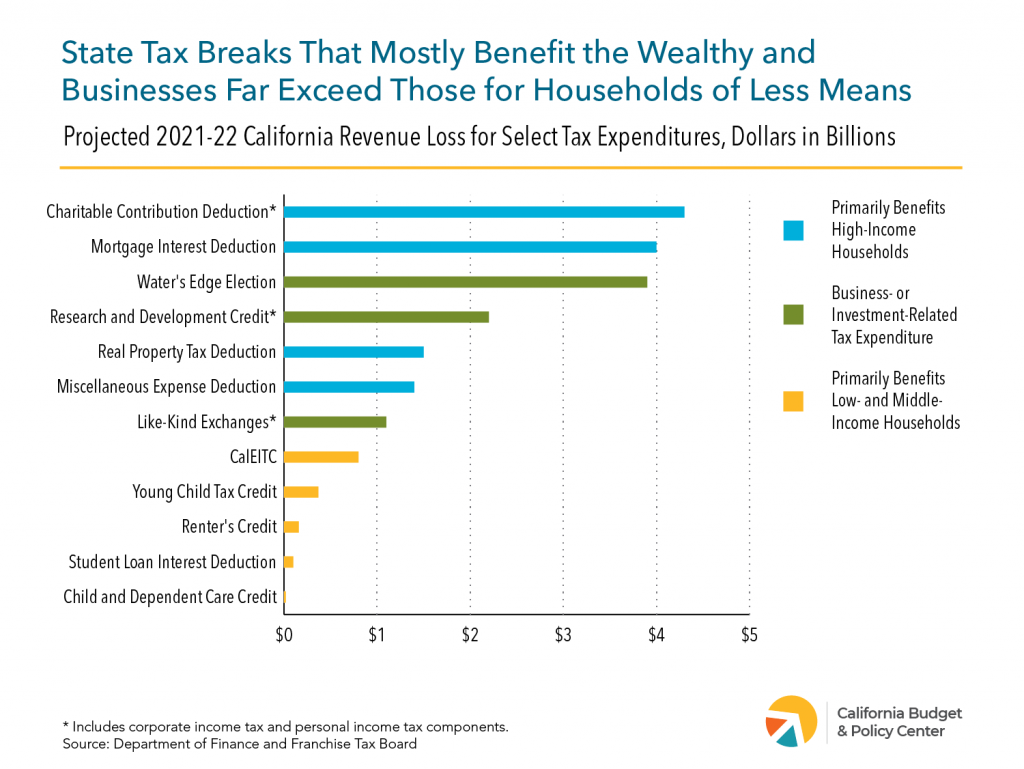

California and many other states allow corporations to take advantage of a loophole known as the water’s edge election, which enables this type of tax avoidance. This provision allows corporations to choose whether or not to include the income held by their foreign subsidiaries in their overall income when calculating the share that is taxable in California.9Generally, corporations determine the share of their total income that is taxable in California based on the share of their total sales that are made to California customers. This gives these corporations an incentive to shift profits abroad to avoid state taxes, and also gives them the option of choosing whichever of the two methods will result in the lowest tax liability. The water’s edge election is projected to cost the state an estimated $4.4 billion in 2022-23.10Department of Finance, Tax Expenditure Report 2022-23, 11, https://dof.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/352/Forecasting/Revenue_and_Taxation/TaxExpenditureReport.pdf.

The most comprehensive option to address this type of tax avoidance would be to eliminate the water’s edge election and require corporations to include their worldwide income as a starting point when calculating the share of their income subject to California taxes. This approach is known as “worldwide combined reporting,” and was used by California and other states in the past.11See, for example, Darien Shanske, White Paper on Eliminating the Water’s Edge Election and Moving to Mandatory Worldwide Combined Reporting (August 2, 2018), https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3225310. There are also less comprehensive measures that policymakers could consider. One approach that some other states have taken is requiring corporations to just include the profits they have booked in known tax havens for the purpose of computing their state taxes.12See Richard Phillips and Nathan Proctor, A Simple Fix for a $17 Billion Loophole How States Can Reclaim Revenue Lost to Tax Havens (Institution on Taxation and Economic Policy, U.S. PIRG Education Fund, SalesFactor, and American Sustainable Business Council, January 17, 2019), 7-8 and 11-13, https://itep.org/a-simple-fix-for-a-17-billion-loophole/. Another is to explore following the approach that the federal government adopted in 2017 of taxing “global intangible low-taxed income” or “GILTI.”13See Darien Shanske and David Gamage, “Why States Should Tax the GILTI,” State Tax Notes (March 4, 2019), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3374987; and Darien Shanske and David Gamage, “Why States Can Tax the GILTI,” State Tax Notes (March 18, 2019), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3374991. The GILTI regime is, however, complex and imperfect, so this option requires careful consideration and potential modifications to ensure the policy is effective and legally permissible.

Corporate Tax Transparency, Corporate Tax Breaks, and Barriers to Raising Revenues

Beyond the three options discussed here, policymakers should also increase corporate tax transparency, scale back corporate tax breaks, and address barriers to raising revenues. These steps would help make the state’s corporate tax system — and the state’s revenue system as a whole — more fair and effective.

First, greater transparency is needed to shed light on the extent to which corporations are engaging in questionable tactics to minimize or wipe out their state liability. This includes stronger data reporting requirements, which can be structured to avoid jeopardizing taxpayer privacy.

Policymakers should also examine the specific corporate tax breaks that already exist in the state’s tax code. These tax breaks should be regularly reviewed and subject to nonpartisan evaluation to determine if and how well they are achieving their policy goals, what types of corporations receive the most benefits, and whether they should be retained, reformed, or eliminated.

Finally, the state’s constitutional spending cap (the Gann Limit) poses challenges to any policy change that raises significant revenues, since substantial new revenues will push the state closer to or above the spending cap, and revenues above the cap are restricted to being spent in specific ways. This limits the ability of state leaders to use revenues to address the most pressing challenges faced by Californians. Policymakers could raise significant revenues and avoid this limitation by using the new revenues for tax benefits that improve the economic and social well-being of Californians with low and middle incomes — such as expanding the California Earned Income Tax Credit and Young Child Tax Credit. With this approach, revenues would not increase on net, allowing the state to avoid going over the spending cap and facing a restriction on how those revenues could be used. For policymakers to have more flexibility in spending significant new revenues — beyond investing them in tax benefits for people with low or moderate incomes — it will be necessary to reform the Gann Limit.